Quantum systems can be manipulated with extremely high precision, but not perfectly. Researchers in the Department of Physics at ETH Zurich have now demonstrated how to monitor and correct errors that occur during such operations.

The field of quantum computation has seen tremendous progress in recent years. Increasingly, quantum devices are challenging conventional computers, at least at a handful of selected tasks. Current advances notwithstanding, today’s quantum information processors still struggle to cope with errors, which inevitably occur in any calculation. This inability to rectify errors efficiently hinders efforts toward sustained, large-scale processing of quantum information. Now, a set of experiments by the group of Jonathan Home at the Institute for Quantum Electronics has, for the first time, integrated a range of elements needed for performing quantum error correction in a single experiment. These results have been published today in the journal Nature.

Making imperfection tolerable

Just like their classical counterparts, quantum computers are built from imperfect components, and they are far more sensitive to disturbances from the outside. This leads inescapably to errors as calculations are executed. For conventional computers, there exists a well-established toolkit for detecting and correcting such errors. Quantum computers will rely even more on locating and fixing errors. This requires conceptually different approaches that take into account the fact that information is encoded in quantum states. In particular, reading out quantum information repeatedly without disturbing it, a requirement for detecting errors, and reacting in real time to reverse these errors pose considerable challenges.

Repeat performance

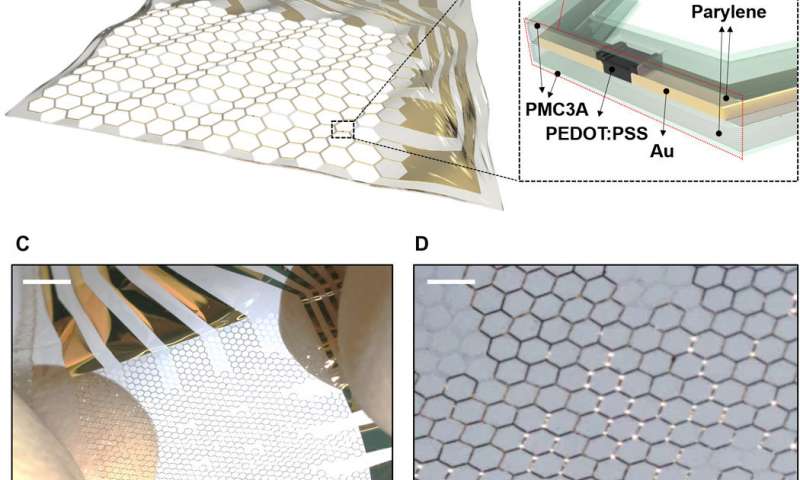

The Home group encodes quantum information in the quantum states of single ions that are strung together in a trap. Typically, these strings contain ions of only one species. But Ph.D. students Vlad Negnevitsky and Matteo Marinelli, together with postdoc Karan Mehta and further colleagues, have now created strings in which they trapped two different species—two beryllium ions (9Be+) and one calcium ion (40Ca+). Such mixed-species strings have been produced before, but the team has used them in novel ways.

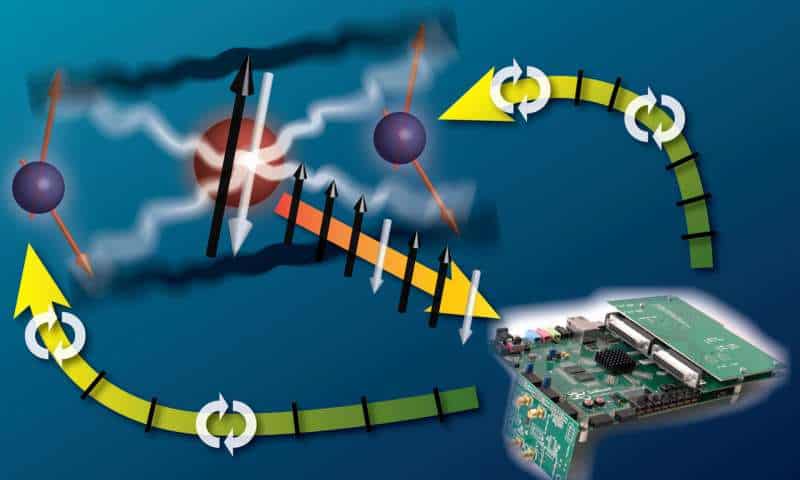

They made use of the distinctly different properties that the two species possess. In particular, in their experiments, they manipulated and measured beryllium and calcium ions using different colours of light. This opens up an avenue for working on one species without disturbing the other. At the same time, the ETH researchers found ways to let the unlike ions interact with one another such that measurements on the calcium ion yield information about the quantum states of the beryllium ions, without corrupting those fragile states. Importantly, the physicists monitored the beryllium ions repeatedly as they were subjected to imperfections and errors. The team performed 50 measurements on the same system, whereas in previous experiments (where only calcium ions were used), such repeated readout has been limited to only a few rounds.

Corrective action

Spotting errors is one thing; taking action to rectify them another. To do the latter, the researchers developed a powerful control system for repeatedly nudging the beryllium ions depending on how much they strayed away from the target state. Bringing the ions back on track required complex information processing on the timescale of microseconds. As the system uses classical control electronics, the approach now demonstrated should be useful also for quantum computation platforms based on information carriers other than trapped ions.

Importantly, Negnevitsky, Marinelli, Mehta and their co-workers demonstrated these techniques can also be used to stabilize states in which the two beryllium ions share entangled quantum states, which have no direct equivalent in classical physics. Entanglement is one ingredient that endows quantum computers with unique capabilities. Moreover, entanglement can also be used to enhance the accuracy of precision measurements. Ingredients for error correction such as the ones now demonstrated can make these states last longer—providing intriguing prospects not only for quantum computation but also for metrology.