Tesla and other proponents of virtual power plants and demand management schemes have scored a significant win after the country’s main energy market rule maker gave its support to the idea that they can compete freely on the wholesale electricity market.

The decision announced by the Australian Energy Market Commission on Thursday is likely to encourage new players in the market to aggregate solar and battery storage installed in homes and businesses, as well as load controls, in a major shift to the way demand and supply is managed.

It is also likely to encourage proponents of technologies that would manage the charging of electric vehicles, and the use of their combined battery capacity in the grid, and it could encourage peer-to-peer trading.

In short, it means that customers with battery storage and electric vehicles can strike contracts with providers other than their main retailers to provide power to the grid when needed. It sets a signal that the Australian grid is finally moving to embrace 21st century technologies.

That said, the AEMC – after years of deliberation and after initially rejecting the idea – has only given approval in principle. The idea still awaits a specific rule request that will likely repeat the battle between the proponents of new technologies, and those locked in the past.

Having such mechanisms will likely be a blow to the major incumbent generators, particularly those – like Snowy Hydro – who rely on the existence of peak pricing events and the subsequent demand for market caps to underwrite their power plants, and particularly the proposed Snowy 2.0 pumped hydro scheme.

The federal government-owned Snowy Hydro was one of the most vocal opponents of the proposal, saying such a move could “reduce short-term high spot prices” and arguing that this would not necessarily be in the “overall interest of consumers.”

The decision by the AEMC in its Reliability Frameworks Review shapes up a major victory for the likes to Tesla, sonnen, Simec Zen, Reposit, Redback, Sunverge, and others who have argued for the development of “virtual power plants”.

These are essentially rooftop solar and battery storage installations located “behind the meter” in homes and businesses which are connected by software. These “distributed energy resources” can be harnessed to help moderate prices and meet demand peaks.

Providers of demand response technologies, such as EnerNoc, who use load controls to reduce non-essential demand at certain times, have also supported the move.

The argument is that these technologies are cheaper, cleaner, smarter and faster than the current default response – which is to switch on dirty and expensive “peaking plants” powered by gas, diesel or even jet fuel.

Their case has been underlined by the performance of the Tesla big battery in South Australia, an early trial of Tesla’s proposed virtual power plant in Adelaide, and the success of other VPP trials and the big battery and demand response in the frequency and ancillary services market.

An example of how these projects can work is revealed in the US state of Vermont, where utility Green Mountain Power drew on electricity from 500 Tesla Powerwall batteries installed in about 400 homes to address peak demand.

The savings from wholesale electricity costs were so great – $US500,000 in one 1-hour peak demand period on July 5 – that GMP is able to offer the Powerwalls to consumers at just one-fifth of their normal price – $US1,500, or $15 a month – in exchange for being able to use some of the storage at certain times.

The companies operating in the Australian market, and some public interest groups, had fought for the same right to be recognised on equal footing with traditional fossil fuel generators, and to allow consumers to engage multiple retailers/aggregators at the same connection point.

“An active demand-side characterised by the active participation of consumers promotes efficient outcomes in the wholesale market,” the AEMC said in its concluding report.

Demand response has also been supported by the Australian Energy Market Operator, and particularly its CEO Audrey Zibelman, who has wanted to repeat the success of demand response in the US, where it accounts for up to 20 per cent of peak demand, in Australia.

However, the AEMC has rejected another key AEMO request – that of creating so-called “day ahead markets,” which it had argued was crucial to its ability to manage the grid and create price signals to the market. This proposal was also fought by incumbent generators.

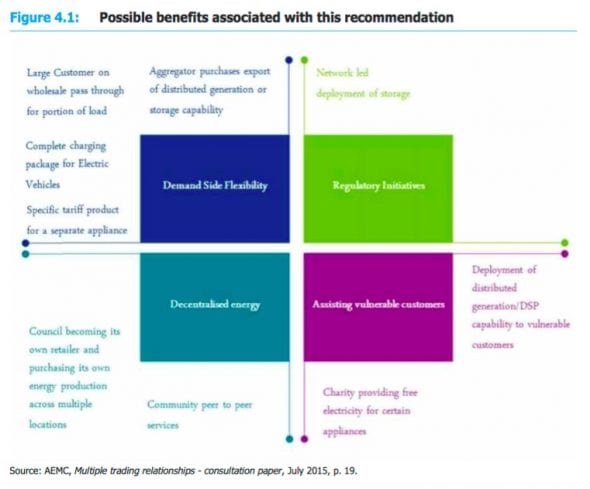

The potential benefits for the AEMC ruling are summed up in this table above. But note the date when this was produced – in 2015. A year later, the AEMC declared it saw no barriers to demand management.

The change of heart has been a long time coming, and it’s not as though the likes of Tesla and others will be able to go out and offer these services tomorrow, as it still requires a specific rule change and more consideration.

The AEMC has said it is OK with the idea. But it notes that consumer advocacy groups the Total Environment Centre (TEC) and Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) have committed to presenting a rule change request soon. The devil will be in the detail of those proposals, and the response.

The AEMC notes that the increasing uptake of distributed energy resources, including solar PV, batteries, electric vehicles and dynamic controllable loads supports its decision.

“A formerly passive demand side is becoming increasingly engaged through the uptake of distributed energy resources which are greatly expanding the choices that consumers have to manage their energy needs at the household/business level,” it notes.

“(These resources) have the potential to provide value to consumers and NEM participants through the provision of wholesale services (such as FCAS) or network services (such as network congestion management).”

It notes the growing number of virtual power plants, where distributed energy resources are being orchestrated to provide services on a wholesale level.

These include Simply Energy’s virtual power plant, the AGL virtual power plant, and the South Australian Power Networks virtual power plant.

It noted that owners of EVs would be able to establish a separate retail relationship for their electric vehicle and maintain their existing retail relationship. “Implementing this arrangement would also allow for innovate approaches to retailing electric vehicle load to emerge,” it noted.

Note: The AEMC also released a report on frequency control, in which it recommends no immediate changes, but recognises there are some “existing inefficient regulatory barriers” that may hinder or prevent distributed energy resources from providing these services.

It makes recommendations, including proposed rule changes, on how these barriers could be addressed.