As the world’s largest natural gas and oil producer and exporter, Russia plays an important role in setting the global geopolitical agenda. The recent agreement with OPEC is evidence of Moscow’s ability to set prices. However, in another field of energy production Russia captures an even more dominant position: nuclear technology.

The Russian nuclear industry is one of the oldest and most mature in the world. After the end of the Second World War and the start of the Cold War, nuclear technology was not only essential for security purposes as a deterrent towards the competing power bloc, but also as a sign of prestige. The first nuclear power plant connected to the grid was opened in 1954 in the USSR. Global nuclear power plant construction in later years was dominated by three countries: France, the U.S., and the Soviet Union.

The demise of communism and the end of the Cold War significantly reduced the development of nuclear technology by the Soviet Union’s successor: the Russian Federation. In 2007 President Putin signed a decree in which a government owned holding company was created to solidify the domestic civil nuclear technology sector. The downward spiral steadily reclined and has turned out to be a resounding success.

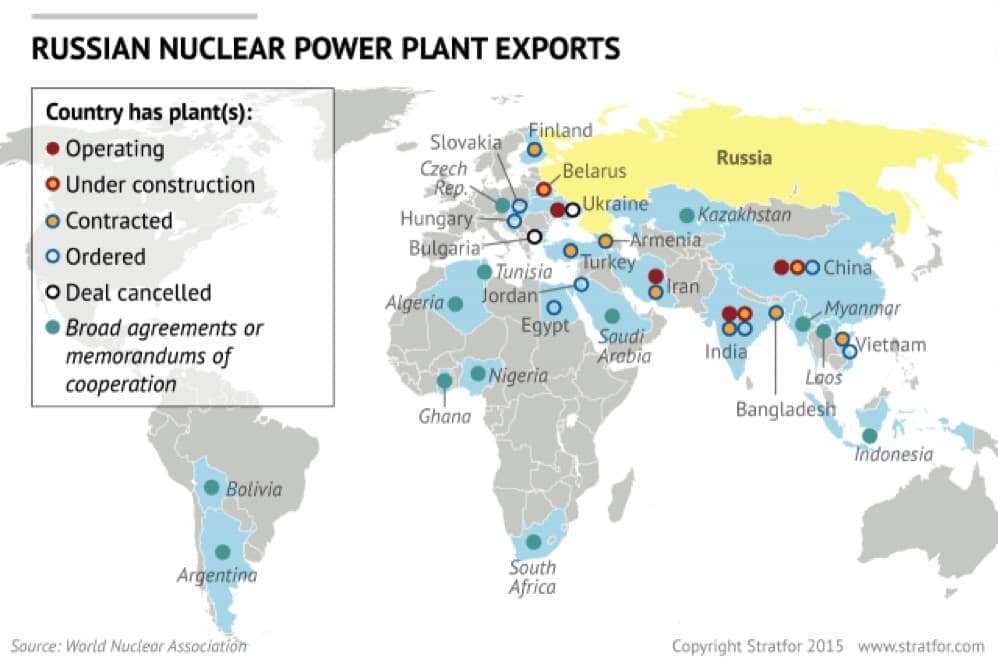

The order book of Russia’s state owned Rosatom has steadily increased to $300 billion dollars in recent years. Currently, 34 reactors in 12 countries are under construction while several other states have shown interest. The order book adds up to a global market share of 60% of all nuclear power plants planned or under construction.

China also hosts an ambitious civil nuclear power sector where the largest number of reactors in a single country is under construction. Beijing’s export-oriented nuclear power technology development, renders risks for Rosatom in the long term. However, despite significant progress made by Chinese developers, Russian reactors remain popular in the Asian country – as illustrated by the recent approval of another four reactors during a state ceremony in Beijing.

Russian civil nuclear technology appeals to a host of customers due to attractive agreements. To many, the power plants will be the first in their history while several locations are in the developing world. In most cases, Russia’s nuclear packages are attractive as Rosatom provides both financing and day-to-day management of the power plants as well as actual construction and the shipping of nuclear fuel. Furthermore, Rosatom offers far greater discounts than its competitors.

Previously, the civil nuclear power sector was dominated by western firms: Areva and Westinghouse (part of Toshiba). The major success of Rosatom abroad coupled with a declining demand for civil nuclear technology in the West, has reduced the flow of revenues for these companies. Westinghouse even filed for bankruptcy, but has been able to reach a deal with its creditors to resolves some of the financial issues.

However, Rosatom – and therefore Moscow – also faces risks. If all plans are executed according to plan, the Russian company will be facing a mountain of nuclear waste, which (in some cases) it is contractually obliged to take care of. Furthermore, the hazardous waste also needs to be protected against theft, with a real threat of terrorists or criminals getting their hands on it.

Moscow’s strong support for national champions in various sectors such as oil and gas (Rosneft and Gazprom), defence (Rosoboronexport), and nuclear energy (Rosatom) is not solely based on financial reward. High profile deals in these crucial sectors also provide the Kremlin diplomatic clout in the countries concerned.

Furthermore, the civil nuclear energy sector is highly sensitive to public perception. Changes in attitude can quickly halt or rollback developments. The multiple methods of electricity production provide alternatives for decision makers in case the nuclear option falls out of grace. The disaster with the plant at Fukushima is the most recent example of the world’s love-hate affair with civil nuclear energy. The meltdown at the Japanese power plant dramatically changed the energy policy of the third and fourth largest economies of the world: Japan and Germany. As a result, demand for LNG and investment in renewable energies has skyrocketed in recent years in these countries.

Although Rosatom’s order book is already impressively full and several potential orders could be concluded in the foreseeable future, unforeseen actions can seriously hamper developments. The high-risk nature of the nuclear energy business renders unique mitigating factors unlike others in the power production business. As the nuclear energy sector is highly dependent on reputation and safety, one mistake or accident could break Rosatom’s winning streak overnight.