Matthew Chamberlain had just presided over one of the wildest days in the history of metals markets when he sat down to type a late-night memo to the UK’s financial regulator. But the London Metal Exchange’s chief executive was optimistic.

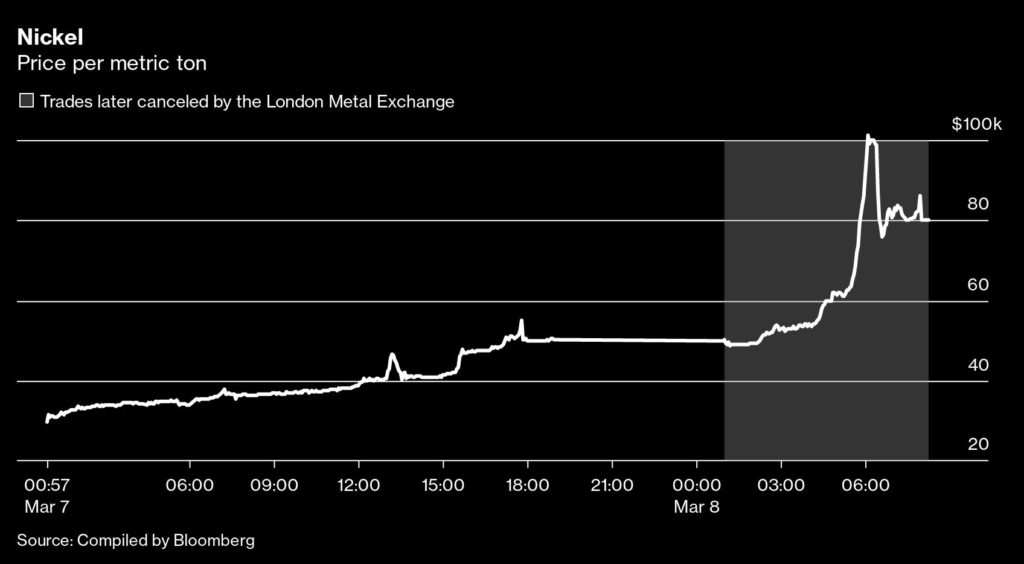

It was the evening of March 7 last year and nickel prices had surged as much as 90% to an unprecedented $55,000 a ton, causing huge strains across the market. A large Chinese bank had missed a margin call in the hundreds of millions of dollars. The Financial Conduct Authority was beginning to demand updates.

Now, after a long day of meetings, calls, and emails, Chamberlain summed up the LME’s position: the price spikes were explainable because of jitters over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the market was still functioning. It didn’t see a need to intervene.

“We will see where we stand 0800-0900 tomorrow,” Chamberlain wrote. “If the nickel price has fallen overnight, we’ll be in a much better position.” At 9:36 p.m., he pressed send.

By the time he woke up at 5:30 a.m., the market was in chaos.

The broad outlines of what happened in the nickel market last year are by now well known. Prices did start rising because of worries over Russian supply, but by the time of Chamberlain’s memo the nickel market was in the grips of a violent squeeze centered around a short position built by Xiang Guangda of Tsingshan Holding Group Co., the world’s top nickel and stainless steel producer. A few hours after Chamberlain woke up, the LME announced it was cancelling all nickel trades that had taken place on March 8.

Now, documents made public in a court hearing this week recount in unforgiving detail the LME’s fateful decisions in early March, and how it sleepwalked into a crisis with little precedent in the modern history of finance.

Across 649 pages of filings and witness statements, they reveal that the LME was largely in the dark about Tsingshan’s role as the major driver of the price spike until after it had decided to cancel billions of dollars of nickel trades; that the exchange’s top decision-makers were asleep as the market spiraled out of control; and that Chamberlain made the key decision that the market was disorderly in about 20 minutes after he woke up on March 8 – unaware until much later that the LME’s staff had allowed prices to move more rapidly by disabling its own automatic volatility controls.

Death spiral

The LME has acknowledged that it has lessons to learn from the events of last year but insists it acted in the best interests of the market to avoid a “death spiral” that threatened to bankrupt a dozen banks and brokers and posed a risk to the wider financial system.

“The LME is not meant to be a spectator,” Jonathan Crow, a lawyer for the LME, said in court on Wednesday. “It is meant to be operating an orderly market and then it must intervene in moments of disorder.”

Its handling of the saga has been criticized by everyone from the International Monetary Fund to Citadel Securities’ Ken Griffin. And the crisis threatened the existence of the 146-year-old LME itself. In the words of its chief risk officer, the situation carried “a significant risk of market collapse leaving the LME unable to function as a venue for the world’s non-ferrous metals markets.”

The outcome of the legal battle playing out this week in London’s High Court could be similarly existential for the LME. Hedge fund Elliott Investment Management and trading firm Jane Street are seeking $472 million in damages in a judicial review, but the $12 billion of trades the LME cancelled on March 8 is more than 100 times its annual profit. Even if the LME prevails, it faces an uphill struggle to rebuild its reputation among investors and an ongoing investigation from the FCA.

Big bets

Six months before the crisis, in September 2021, traders at Elliott had started placing a bet that nickel prices would rise. The hedge fund, run by billionaire Paul Singer and best known as an activist shareholder and ferocious litigator, is a significant player in commodity markets with a taste for big wagers.

Around the same time, at Tsingshan’s offices in Shanghai, Xiang was coming to the opposite view. Like Elliott, Xiang, who’s known as ‘Big Shot’ in Chinese commodities circles, also has a history of betting big. He’d built Tsingshan from a modest start into a global metals behemoth, and now he was backing himself to deliver again: with plans to boost production significantly, he reckoned prices could only fall. He started building up a large nickel short position.

By February 2022, it was clear that Elliott’s view of the market was prevailing. Stocks were low, demand for nickel in electric car batteries was booming, and traders were fretting that supplies from Russia could be cut off.

“Wow,” Elliott’s contact at JPMorgan said in an instant message. “We did that at the right time.”

The market started trading in a self-reinforcing cycle, known as a “short squeeze.” Higher prices forced Xiang to post more margin, leading him to reduce his position by buying back contracts – and so pushing up prices further.

Yet the LME remained largely unaware of Tsingshan’s role in driving prices higher as the chaotic events unfolded.

The LME’s senior management first became aware of Tsingshan’s short position when Bloomberg wrote about it on Feb. 14, according to the witness statements. However, while Chamberlain recognized that the position was large, he did not see it as “a particular cause for concern,” and therefore did not request any further information.

Margin calls

Without that, the LME only had access to data about Tsingshan’s on-exchange position, and not the portion of its position that was held bilaterally, or over the counter. Bloomberg has since reported that Tsingshan’s total position was five times the size of the on-exchange part the LME could see.

On the morning of March 7, nickel prices leapt to $36,000 a ton, and the strains were becoming apparent in the market. Four LME brokers were late in paying their margin calls that morning.

One of them, a unit of China Construction Bank Corp., was unable to pay a margin call in the hundreds of millions of dollars for the entire day. It told the LME that the reason was because clients including Tsingshan had not paid margin calls to it.

Defaults are not an everyday occurrence on the LME or any other exchange. The LME’s clearinghouse had never put a member into default since it started operations in 2014. That CCBI, as the unit is known, was unable to pay its margin call was a sign of the extreme stress on the market.

As prices surged, the LME began to hold discussions about whether and how it should respond. The key question at the time, and one raised repeatedly during this week’s legal case, is whether the market had become “disorderly.”

LME executives discussed suspending the market on a call on the morning of March 7. By 1:30 p.m., with prices up 60% for the day, James Cressy, the LME’s chief operating officer said in an email that there was “a question of how orderly the mkt is and whether we suspend.”

Still, nickel continued to trade.

But in recognition of the strains spreading through the market, the LME’s clearinghouse resolved to stop making margin calls until the following morning – giving members more time to find cash, but also potentially exposing LME Clear to a greater risk if prices moved even higher.

When the LME’s “Special Committee” met at 4 p.m., it decided that the market should remain open. The nickel price move could be explained by geopolitical and macroeconomic factors, it concluded, deciding not to impose any limits on the market.

About half an hour later, Chamberlain was forwarded a market commentary from an LME broker that read, “How closely do you need to monitor a market to spot something is not quite right !!!!!!!”

To bed

And when the LME’s key decision makers went to bed, CCBI’s margin call remained unpaid. By that time, the exchange’s executives were becoming increasingly concerned.

At 8:47 p.m. Adrian Farnham, the chief executive of LME Clear, sent a WhatsApp message to Nicolas Aguzin, the chief executive of LME parent company Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing Ltd. He asked Aguzin to try to speak to China Construction Bank, “because obviously we can’t really allow” its CCBI unit “to not pay again.”

Nonetheless, Farnham, like Chamberlain, remained optimistic. “I went to bed expecting that the nickel price would come back down,” he said in a witness statement.

Elliott, on the other hand, was preparing for prices to spike. The hedge fund’s traders sent a series of orders to their broker, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., seeking to sell nickel should the price rise to certain predetermined levels.

The nickel market opened as usual at 1 a.m. As Farnham and Chamberlain slept, the market was calm for a few hours, but then resumed its rise as panicky banks sought to reduce their exposure to Tsingshan by covering part of the short position.

Jane Street alleges the very fact that the LME’s key decision makers were asleep was a breach of the exchange’s regulatory duties, since it meant that “no-one had been monitoring transactions in order to assess whether there were disorderly trading conditions.” The LME disputes that it was in breach.

What oversight there was came from the exchange’s trading operations team. They were in charge of operating the LME’s price bands, a form of speed bump designed to limit extreme price moves, such as in the case of “fat finger” trades.

But in the early hours of March 8, the operations team received numerous complaints from market participants that the price bands were preventing them from booking trades. At 4:49 a.m., they suspended them altogether.

Dizzying ascent

It was soon after this that nickel prices started the most dizzying part of their ascent. By the time Chamberlain woke up, at 5:30 a.m., the price was already $60,000 a ton. In the next 38 minutes, it rose another $40,000.

“The abandonment of price bands caused or at least materially contributed to the speed and scale of the increase in prices,” Jane Street said in its court filing. “Without price bands in place, the LME could not control price volatility at all.”

Chamberlain spent twenty minutes searching on his phone for a real-world explanation for the price move – browsing Bloomberg, the Financial Times and Google – before concluding that the market was disorderly. “I had never witnessed such extreme price movements in nickel (or any other metal traded on the Exchange) before,” he recalled.

Chamberlain wasn’t aware that his operations team had suspended the price bands, as he made his pivotal decision to suspend the nickel market. In his witness statement, he said that the information wouldn’t have affected the decision, as the price would have risen anyway, even if the trading curbs were still in place.

“We are in serious difficulties”

The exchange still didn’t have a handle on the scale or the importance of Tsingshan’s position — the real reason behind the runaway rally.

Gay Huey Evans, the LME’s chair, had asked for an update on Tsingshan’s position the previous evening, but when the FCA asked that morning what was driving the nickel price, an LME staffer did not even mention the possibility of a short squeeze.

“This is, as you’d expect, related to the ongoing situation in Ukraine,” he wrote.

Chamberlain said he “was not aware of Tsingshan being in any difficulty” until later that day.

That morning, CCBI, having enlisted support from its parent company, paid its margin call from the previous day.

Panicking brokers

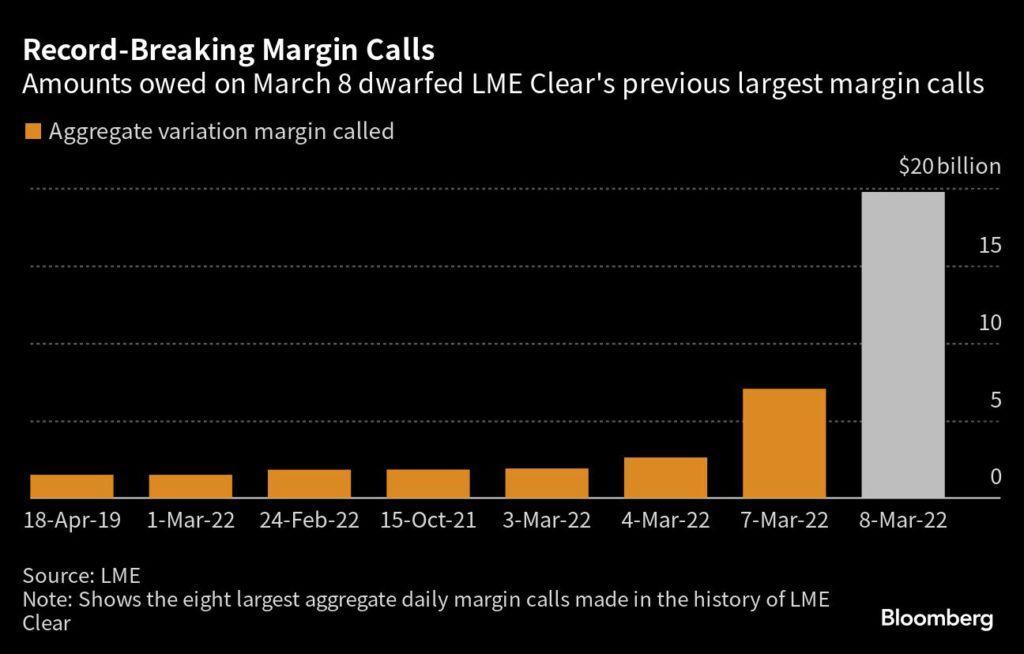

But now there was a new problem. Brokers on the LME would normally need to pay their first margin call of the day by 9 a.m., based on prices prevailing at around 7 a.m. If that had happened on March 8, the LME would have needed to request $19.75 billion from 28 banks and brokers – an unprecedented sum that was more than 10 times the previous daily record before March 2022.

LME executives were bombarded with calls and emails from panicking brokers. “We will not be able to meet intra-day margin calls,” one wrote, warning of their company’s imminent bankruptcy. “We are in serious difficulties and will be invoking actions to halt the business.”

Another requested a call with “someone senior” at the LME to convey their company’s “pain.”

One member, who was among roughly 10 brokers through which Tsingshan held its short position, wrote to Chamberlain saying: “You shouldn’t have opened in Asia – now you have to cancel trades and reset to the London close.”

Suspend the market

At 7:30 a.m., Chamberlain led a conference call for the senior management of LME and LME Clear, as well as several executives from its parent company HKEX. They agreed to suspend the market as soon as possible. No minutes were taken.

By now, Elliott had sold 9,660 tons of nickel at the elevated prices of March 8 via three brokers. The bulk of it was sold, in a single trade, via JPMorgan Chase & Co. – in a deal that was confirmed at 8:14 a.m.

Having sold at an average price of just over $75,000 a ton, Elliott stood to make a profit of around $50,000 a ton on its bullish bet.

“Wow,” Elliott’s contact at JPMorgan said in an instant message. “We did that at the right time.”

But the real bombshell was still to come. At 9 a.m., the LME held a 52-minute call to discuss what to do next. It considered and rejected several options, including allowing the trades of March 8 to stand, allowing them to stand but changing their price, and allowing them to stand but calling margin based on the prices of the previous day. Finally, Chamberlain made the decision to cancel the entire trading session.

On March 9, as recriminations flew and with the nickel market still closed, Chamberlain finally held his first call with Tsingshan.

The same day, Elliott’s lawyers wrote their first letter to the LME.