The promise of a global electric vehicle transformation has a looming problem.

The cathodes in the lithium-ion batteries typically used in electric vehicles, or EVs, are made of metal oxides that contain cobalt, a metal found infinite supplies and concentrated in one of the globe’s more precarious countries.

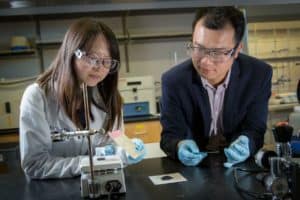

But an assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego says he has developed a way to recycle used cathodes from spent lithium-ion batteries and restore them to the point that they work as good as new.

“Yes, it can work effectively,” said Zheng Chen, a 31-year-old who works as a nano-engineer at the Sustainable Power and Energy Center at the Jacobs School of Engineering.

The method also works on lithium cobalt oxide, which is widely used in electronic devices such as smartphones and laptops.

“In my house I have about six cellphones,” Chen said. “I have probably about five laptops. They all have lithium batteries. I thought, there is no clear system to recycle and retrieve them. From a battery researcher (standpoint) I know this is something we have to face, we have to solve.”

How it works

The process takes degraded particles from the cathodes found in a used lithium-ion battery. The particles are then pressurized in a hot, alkaline solution that contains lithium salt. Later, the particles go through a short heat-treating process called “annealing” in which temperatures reach more than 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit.

After cooling, Chen’s team takes the regenerated particles and makes new cathodes. They then test the cathodes in batteries made in the lab.

The results, Chen said, have been impressive.

The new cathodes have been able to maintain the same charging time, storage capacity and battery lifetime as the originals did.

“I admit I was surprised it became so effective because originally I thought we couldn’t get all this performance back, that we would lose 10 percent or 20 percent,” Chen said. “But it turns out we’re getting exactly the same performance.”

Details of the recycling method were recently published in the research journal Green Chemistry, submitted by Chen and two colleagues.

The next step

Now that the method has been established in the lab, the goal is to optimize the process so it can be economical on an industrial scale.

Right now, the particles have to be picked out manually from the old, conked-out battery. The entire cycle takes about 10 hours to complete, Chen said. Researchers are working on a way to simplify and accelerate the process.

How much would it cost to develop the technology to make it commercially viable?

“It’s very hard to give an accurate number, considering the scale,” Chen said. “I think we definitely need to scale up and make (recycling) meaningful for the market.”

One of the interesting things about the process developed at UC San Diego is that it’s essentially the same one that is used to make the cathode particles in the original batteries.

“We’re taking an old process and applying it to this new problem,” Chen said. “That’s one of the beauties of this process. It’s like you have Lego pieces and you put them together, assemble them and you form this new platform.”

Implications

Less than 3 percent of lithium-ion batteries around the world are recycled. Chen said. The batteries from used smartphones and laptops often end up in landfills or tucked away in drawers and closets.

But the lithium-ion batteries in EVs are much larger, thus producing a long-term challenge as the zero-emissions sector grows and policymakers seek a way to transition away from cars and trucks powered by fossil fuels.

Gov. Jerry Brown wants 5 million zero-emission vehicles on California’s roads by 2030. Recent rules adopted by the government in China are expected to push sales of EVs there to 1 million per year within two years.

It’s harder to recycle batteries found in EVs than lead-acid batteries used in gasoline-powered vehicles because of the number of materials involved and differences in how manufacturers build them.

The cobalt often used in the cathodes of batteries in EVs, smartphones and laptops is concentrated in one country – the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Some 54 percent of the world’s supply comes from the Congo, which has suffered through two violent civil wars in its relatively short history. Human rights groups have documented how child labor is sometimes used to extract the metal that is a byproduct of mining nickel and copper.

There’s also a finite supply of lithium, with the South American country of Bolivia estimated to possess about half of the world’s supply.

Finding a way to recycle lithium-ion batteries on a large scale could greatly reduce the demand – as well as curb the rising costs – for cobalt in electric vehicles.

It can also help alleviate the environmental concerns surrounding aging batteries in smartphones, laptops and other digital devices, as well as EVs.

“The commercial application is huge,” Chen said.

The team at UC San Diego plans to work with battery companies in China and has filed for a provisional patent at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.