Not far from Norway’s North Sea oil rigs, shipbuilders are assembling some of the first ferry boats ever to be powered entirely by batteries.

“If you look at the next five years, this is what we’ll be doing,” said Erlend Hatleberg, a project manager at Havyard Group ASA, which runs the Sognefjord shipyard that’s switched to specializing in boats with battery technology similar to plug-in cars. “We were in a really deep trough. But activity is back.”

Next up, Norway wants two-thirds of all boats carrying both passengers and cars along its jagged and windy Atlantic coastline to be electrified by 2030. Havyard is filling 13 orders for zero-emission ferries received since 2016.

Zooming out, though, the progress may be a drop in the bucket. To really slash maritime pollution would require the 50,000 tankers, freighters and carriers traversing the oceans to switch to renewable energy. The largest use diesel engines as big as a four-story house, with emissions comparable to 64,000 passenger cars.

Without big changes, the International Council on Clean Transportation warns sea transport could be responsible for 17 percent of CO2 emissions by 2050, up from 2-3 percent now. But shipping was omitted from the Paris deal and battery technologies haven’t evolved enough for long ocean voyages, according to the International Maritime Organization, which is set to reveal in April an initial set of guidelines for cutting greenhouse gases.

“Battery technology is simply not competitive and still requires significant further evolution in terms of performance and cost reduction before it could be preferable to synthetic fuel options,” Lloyd’s Register Group, a maritime classification society founded in the 18th century, said in a December report.

For now, electric ships make most sense in populated waterfront areas where they can be recharged easily and improve air quality and noise pollution. Of the 185 battery-powered ships in operation or scheduled for delivery worldwide in 2018, most are in Norway and France, according to DNV GL, a ship classification and assurance company near Oslo.

Norway is particularly suited because its hundreds of fjords—long and narrow inlets of sea water that can stretch hundreds of kilometers inland—make ferries an essential complement to road transportation. By 2021, about 60 battery-powered or hybrid vessels will be in operation, said Edvard Sandvik, who heads the ferry division at Norway’s Public Roads Administration.

The first zero-emissions ferry, called the MF Ampere, started sailing between the villages of Oppedal and Lavik along the Sognefjord in 2015. Operated by Norled AS, it’s made of light aluminium, runs on 10 tons of lithium-ion batteries and carries up to 350 passengers and 120 cars. After each 20-minute journey, it recharges for 10 minutes. The ride is both smoother and quieter than on diesel-powered ferries.

Some initial kinks made the ship lag the two other ferries that travel the same route, frustrating commuters, but it’s since caught up.

“I’m very doubtful that the first steam engine was flawless,” said captain Steinar Johnsen, 47. “If you’re always going to wait for something better, you’re never going to do anything.”

In the Netherlands, Port-Liner BV will deploy five, 52-meter container barges powered by 20-foot batteries this year that can cruise for 15 hours, says chief executive officer, Ton van Meegen. He predicts they’ll divert some 23,000 trucks from European roads when they start servicing ports in and around Antwerp, Belgium, and Dutch cities Amsterdam and Rotterdam.

Also in the pipeline: 10 boats capable of running for 35 hours on four, 20-foot-long batteries. They’ll cut 18,000 cubic tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere, he said.

“The technology, all the new ideas, are moving very very fast,” Van Meegen said. “I don’t know what will happen in the next 50 years, but it will be a completely different world.”

Europe’s 7,300 inland ships will eventually make the switch under global rules that require all transport, with the exception of planes, to use greener technologies by 2050. Their motors are already a third cheaper than typical diesel varieties going for 350,000 euros ($434,000), Van Meegan said. But batteries—made by the likes of Corvus Energy in Canada—drive up costs.

Regulations are also lagging. The IMO hasn’t yet set out rules to govern sailorless ships, even though companies are racing to design them.

Port-Liner’s Dutch barges can be fully automated, while a unit of Norwegian technology company Kongsberg Gruppen ASA will have a 79.5-meter, battery-powered, open-top container ship ready by 2020. Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc predicts its first unmanned ocean-going ship will make its first voyage as soon as 2035.

Back in Norway, where national and regional governments spend 3 billion kroner ($386 million) a year to operate the 200 ferries serving 130 routes, Hatleberg is counting on orders continuing. Before the electric boat fad, the yard cut more than a quarter of its workforce.

Electric Shock

Note: All figures at year end, except 2018, which includes new orders and hasn’t been adjusted for completed deliveries

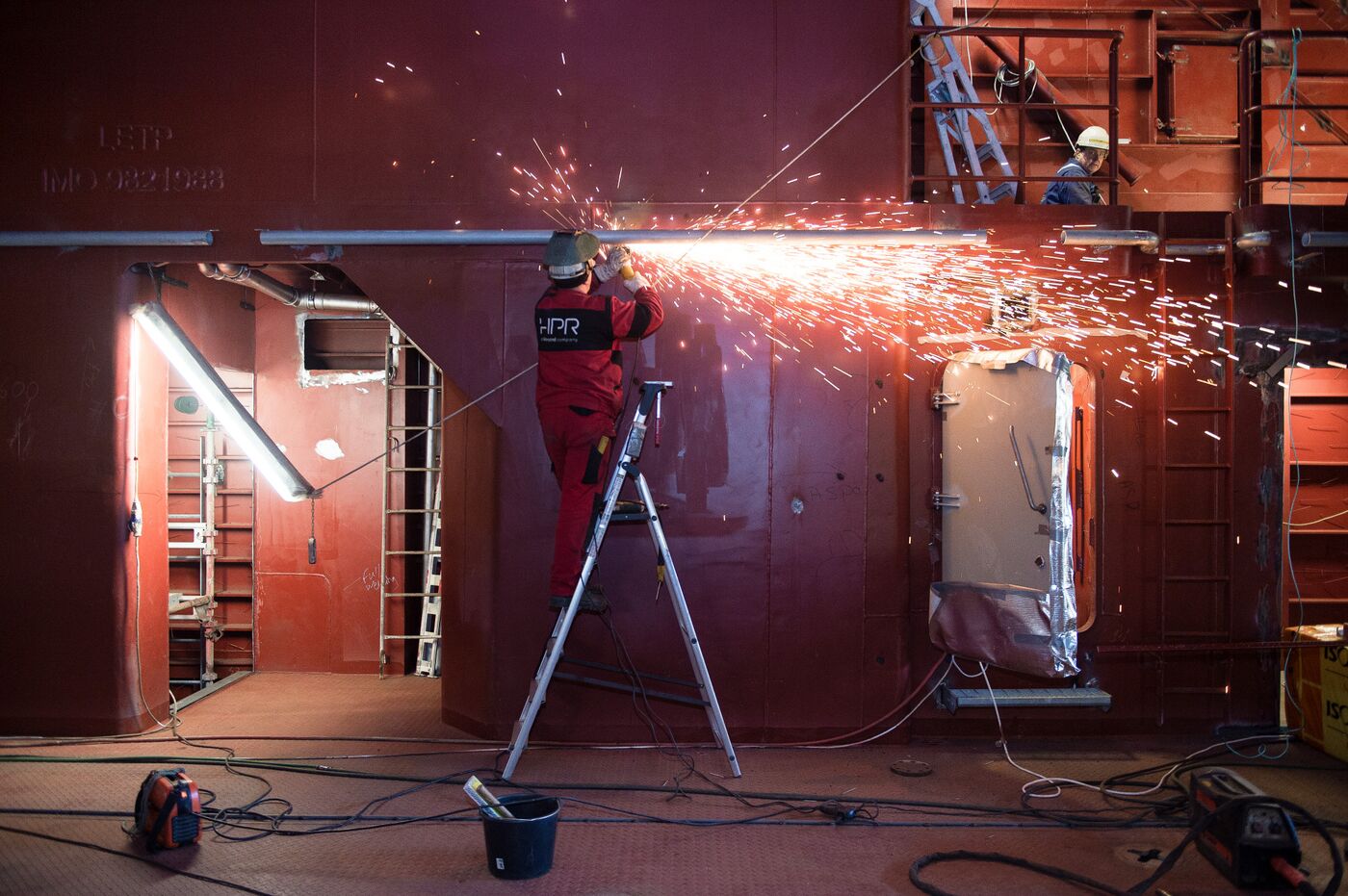

On an icy day in late February, some 120 shipwrights were welding, hammering and laying 75,000 meters of cables over the newest ferry, the 67-meter, 2,100 ton MF Husavik, slated for delivery to ferry operator Fjord1 ASA as early as May.

“We finally have work again,” Hatleberg said. “It’s a pretty tough project. But people are enthusiastic, there’s an extreme will to make this happen.”