The story of steel begins long before bridges, I-beams, and skyscrapers. It begins in the stars.

Billions of years before humans walked the Earth—before the Earth even existed—blazing stars fused atoms into iron and carbon. Over countless cosmic explosions and rebirths, these materials found their way into asteroids and other planetary bodies, which slammed into one another as the cosmic pot stirred. Eventually, some of that rock and metal formed the Earth, where it would shape the destiny of one particular species of walking ape.

On a day lost to history, some fortuitous humans found a glistening meteorite, mostly iron and nickel, that had barreled through the atmosphere and crashed into the ground. Thus began an obsession that gripped the species. Over the millennia, our ancestors would work the material, discovering better ways to draw iron from the Earth itself and eventually to smelt it into steel. We’d fight over it, create and destroy nations with it, grow global economies by it, and use it to build some of the greatest inventions and structures the world has ever known.

Metal From Heaven

King Tut had a dagger made of iron—a treasured object in the ancient world worthy of few more than a pharaoh. When British archaeologist Howard Carter found Tutankhamun’s tomb nearly a century ago and laid eyes on this object, it was clear the dagger was special. What archaeologists didn’t know at the time was that the blade came from space.

Iron that comes from meteorites has a higher nickel content than iron dug up from the ground and smelted by humans. In the years since Carter’s big discovery, researchers have found that not only King Tut’s dagger but also virtually all iron goods dating to the Bronze Age were made from iron that fell from the sky.

To our ancestors, this exotic alloy must have seemed like it was sent by entities beyond our understanding. The ancient Egyptians called it biz-n-pt. In Sumer, it was known as an-bar. Both translate to “metal from heaven.” The iron-nickel alloy was supple and easily hammered into shape without breaking. But there was an extremely limited supply, brought to Earth only by the occasional extraterrestrial delivery, making this metal of the gods more valuable than gems or gold.

It took thousands of years before humans started looking beneath their feet. Around 2,500 BC, tribesmen in the Near East discovered another source of dark metallic material hidden underground. It looked just like the metal from heaven—and it was, but something was different. The iron was mixed with stones and minerals, lumped together as ore. Extracting iron ore wasn’t like picking up a stray piece of gold or silver. To remove iron from the subterranean realms was to tempt the spirit world, so the first miners conducted rituals to placate the higher powers before digging out the ore, according to the 1956 book The Forge and the Crucible.

But pulling iron ore from the Earth was only half the battle. It took the ancient world another 700 years to figure out how to separate the precious metal from its ore. Only then would the Bronze Age truly end and the Iron Age begin.

The Long Road to the First Steel

To know steel, we must first understand iron, for the metals are nearly one and the same. Steel contains an iron concentration of 98 to 99 percent or more. The remainder is carbon—a small additive that makes a major difference in the metal’s properties. In the centuries and millennia before the breakthroughs that built skyscrapers, civilizations tweaked and tinkered with smelting techniques to make iron, creeping ever closer to steel.

Around 1,800 BC, a people along the Black Sea called the Chalybes wanted to fabricate a metal stronger than bronze—something that could be used to make unrivaled weapons. They put iron ores into hearths, hammered them, and fired them for softening. After repeating the process several times, the Chalybes pulled sturdy iron weapons from the forge.

What the Chalybes made is called wrought iron, one of a couple major precursors to modern steel. They soon joined the warlike Hittites, creating one of the most powerful armies in ancient history. No nation’s weaponry matched a Hittite sword or chariot.

Steel’s other younger sibling, so to speak, is cast iron, which was first made in ancient China. Beginning around 500 BC, Chinese metalworkers built seven-foot-tall furnaces to burn larger quantities of iron and wood. The material was smelted into a liquid and poured into carved molds, taking the shape of cooking tools and statues.

Neither wrought nor cast iron was quite the perfect mixture, though. The Chalybes’ wrought iron contained only 0.8 percent carbon, so it did not have the tensile strength of steel. Chinese cast iron, with 2 to 4 percent carbon, was more brittle than steel. The smiths of the Black Sea eventually began to insert iron bars into piles of white-hot charcoal, which created steel-coated wrought iron. But a society in South Asia had a better idea. India would produce the first true steel.

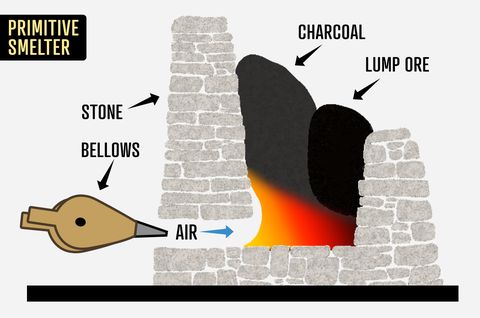

Around 400 BC, Indian metalworkers invented a smelting method that happened to bond the perfect amount of carbon to iron. The key was a clay receptacle for the molten metal: a crucible. The workers put small wrought iron bars and charcoal bits into the crucibles, then sealed the containers and inserted them into a furnace. When they raised the furnace temperature via air blasts from bellows, the wrought iron melted and absorbed the carbon in the charcoal. When the crucibles cooled, ingots of pure steel lay inside.

India’s ironmasters shipped their “wootz steel” across the world. In Damascus, Syrian smiths used the metal to forge famous, almost mythological “Damascus steel” swords, said to be sharp enough to cut feathers in midair (and inspiring fictional supermaterials like the Valyrian steel of Game of Thrones). Indian steel made it all the way to Toledo, Spain, where smiths hammered out swords for the Roman army.

In shipments to Rome itself, Abyssinian traders from the Ethiopian Empire served as deceitful middlemen, deliberately misinforming the Romans that the steel was from Seres, the Latin word for China, so Rome would think that the steel came from a place too distant to conquer. The Romans called their purchase Seric steel and used it for basic tools and construction equipment in addition to weaponry.

Iron’s days as a precious metal were long over. The fiercest warriors in the world would now carry steel.

Holy Swords and Samurai Steel

According to legend, the great sword Excalibur was imposing and beautiful. The word means “cut-steel.” But it wasn’t steel. From the age of King Arthur through Medieval times, Europe lagged behind in iron and steel production.

As the Roman Empire fell (officially in 476), Europe spun into chaos. India still made its sensational steel, but it couldn’t reliably ship the metal to Europe, where the roads were unkempt, merchants were ambushed, and people feared plague and illnesses. In Catalonia, Spain, ironworkers developed furnaces similar to those in India; the “Catalan furnace” produced wrought iron, and lots of it—enough metal to make horseshoes, wheels for carriages, door hinges, and even steel-coated armor.

Knights brandished specially crafted swords. They were forged by twisting rods of iron, a process that left unique herringbone and braided patterns in the blades. The Vikings interpreted the designs as dragon coils, and swords like King Arthur’s Excalibur and El Cid’s Tizona became mythological.

The best swords in the world, however, were made on the other side of the planet. Japanese smiths forging blades for the samurai developed a masterful technique to create light, deadly sharp blades. The weapons became heirlooms, passed down through generations, and few gifts in Japan were greater. The forging of a katana was an intricate and ritualized affair.

Japanese smiths washed themselves before making a sword. If they were not pure, then evil spirits could enter the blade. The metal forging began with wrought iron. A chunk of the material was heated with charcoal until it became soft enough to fold. After it cooled, the iron was heated and folded about 20 more times, giving the blade its arcing shape, and all through the forging and folding, the wrought iron’s continued exposure to carbonaceous charcoal turned the metal into steel.