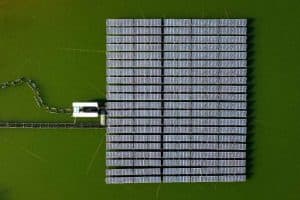

A vast array of solar panels floats on the shimmering waters of a reservoir in northeast Thailand, symbolising the kingdom’s drive towards clean energy as it seeks carbon neutrality by 2050.

The immense installation, covering 720,000 square metres of water surface, is a hybrid system that converts sunlight to electricity by day and generates hydropower at night.

Touted by the authorities as the “world’s largest floating hydro-solar farm”, the Sirindhorn dam project in the northeastern province of Ubon Ratchathani is the first of 15 such farms Thailand plans to build by 2037.

The kingdom is stepping up efforts to wean itself off fossil fuels, and at the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow last year, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-O-Cha set the target of carbon neutrality by 2050 followed by a net-zero greenhouse emissions by 2065.

The Sirindhorn dam farm—which began operations last October—has more than 144,000 solar cells, covering the same area as 70 football pitches, and can generate 45 MW of electricity.

“We can claim that through 45 megawatts combined with hydropower and energy management system for solar and hydro powers, this is the first and biggest project in the world,” Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) deputy governor Prasertsak Cherngchawano told AFP.

The hybrid energy project aims to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 47,000 tonnes per year and to support Thailand’s push toward generating 30 percent of its energy from renewables by 2037, according to EGAT.

Green shift

But hitting these targets will require a major revamp of power generation.

Thailand still relies heavily on fossil fuel, with 55 percent of power derived from natural gas as of October last year, compared with 11 percent from renewables and hydropower, according to the Energy Policy and Planning Office, a department of the ministry of energy.

EGAT plans to gradually install floating hydro-solar farms in 15 more dams across Thailand by 2037, with a total power generation capacity of 2,725 MW.

The $35 million Sirindhorn project took nearly two years to build—including Covid-19 hold-ups caused by delays to solar panel deliveries and technicians falling sick.

Most of the electricity generated by the floating hydro-solar farm goes to the provincial electricity authority, which distributes power to homes and businesses in provinces in the lower northeastern region of Thailand.

Tourism potential

As well as generating power, officials hope the giant solar farm will also prove a draw for tourists.

A 415-metre (1,360-foot) long “Nature Walkway” shaped like a sunray has been installed to give panoramic views of the reservoir and floating solar cells.

“When I learned that this dam has the world’s biggest hydro-solar farm, I knew it’s worth seeing with my own eyes,” tourist Duangrat Meesit, 46, told AFP.

Some locals have reservations about the floating hydro-solar farm, with fishermen complaining they have been forced to change where they cast their nets.

“The number of fish caught has reduced, so we have less income,” village headman Thongphon Mobmai, 64, told AFP.

“But locals have to accept this mandate for community development envisioned by the state.”

But the electricity generating authority insists the project will not affect agriculture, fishing or other community activities.

“We’ve used only 0.2 to 0.3 percent of the dam’s surface area. People can make use of lands for agriculture, residency, and other purposes,” said EGAT’s Prasertsak.