Every day, Ross Gerber checks his email for a message from Tesla Inc. Then he checks it again. And again. And again. Gerber is one of the half-million people with a reservation for the Model 3, Tesla’s latest electric sedan, and he’s been waiting two years for his number to come up. His clients at Gerber Kawasaki Wealth and Investment Management, who own more than $10 million in Tesla shares, are just as eager to have more customers get good-news emails from Tesla—soon.

“You found the crazy guy,” Gerber says, laughing about his obsession.

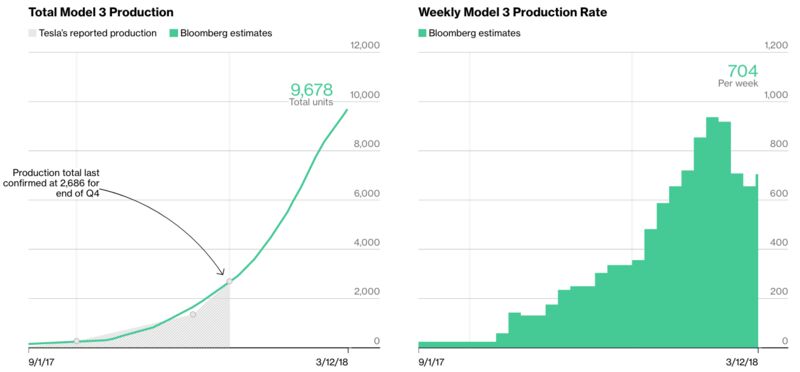

The Model 3 production rate is of existential importance to Tesla, which blew through almost $3.5 billion last year getting ready to crank out what Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk promises will be the world’s biggest-selling electric car. Tesla expects to eventually reach annual sales of more than 500,000, with enough popularity in the U.S. to outpace the top-selling luxury cars—about 113,000 BMW 3 Series and Mercedes C-Class sedans were sold last year, combined.

“Our Model 3 production plan includes periods of planned downtime in both Fremont and Gigafactory 1,” Tesla said in an emailed statement. “These periods are used to improve automation and systematically address bottlenecks in order to increase production rates.”

The unusual focus on manufacturing numbers is a problem of Tesla’s own making. While most car companies report sales every month, Tesla releases its numbers only quarterly. That leaves a lot of time for speculation, with fortunes hanging in the balance. The last time Tesla reported Model 3 production, on Jan. 3, analysts and investors were caught off guard by unexpectedly low numbers. Tesla lost as much as $700 million in market value the morning after the release, and bond prices tumbled.

So Wall Street speculators and Tesla fans have taken matters into their own hands, and some of these homebrewed estimates can be prescient.

Bozi Tatarevic, an automotive writer based in North Carolina, first spotted indications of Tesla’s production woes back in December by scouring U.S. import records for parts Tesla buys from overseas suppliers. He focused on wheel covers and small 12-volt batteries used to power some of the Model 3 electronics. By dividing the weight of the shipping pallets by the weight of the parts, Tatarevic came up with some upper limits for Tesla’s possible production, which were lower than Tesla forecast at the time.

“If they only have 2,000 of a part,” he explains, “that means they’re only going to be able to produce 2,000 cars with that part until they get the next shipment.”

Tatarevic has driven a Model 3 and has inspected a stripped-down body of the car. He says the fit and finish of the early models wasn’t up to top manufacturing standards, although the car “handled very well” and he found it well-designed. “Overall, if they can figure out how to build it, I think it will be successful.”

Tatarevic made a final guess at Tesla’s total Model 3 output in 2017 that was just a few dozen cars off Tesla’s actual production figure of 2,685. He relied on vehicle identification numbers (VINs), which are registered with safety regulators and displayed on every new car sold in the U.S. Tesla switched a batch of unused VINs it registered in 2017 into 2018 production, signaling precisely how many VINs the company had used by year’s end. It was a once-a-year trick.

The first person to automate a system to collect VIN registrations, which also helps power Bloomberg’s Model 3 Tracker, was Alex Halcomb, a 29-year-old who works in data analytics for a startup in San Francisco. He’s a Tesla investor and reservation holder who has his heart set on a blue Model 3, with the premium upgrades package.

Halcomb realized that, in order to pluck all of the registered VIN data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) website, he first had to get around the captcha barrier that seeks to block automated programs such as his from systematically scraping data. To do this, Halcomb figured out a digital vulnerability in how NHTSA communicates with manufacturers and inserted his query at that point. This hack worked for a few weeks, until NHTSA caught on and made its process more secure. Now, when Halcomb’s program gets foiled, it simply closes the browser session and starts anew.

His fully automated system even comes with a Twitter bot, @Model3VINs, which alerts its 1,700 Twitter followers whenever Tesla registers additional VINs.

“There’s a lot of people interested in this information,” says Halcomb, who invested his own life savings in Tesla stock around the time the company started production of the Model S electric sedan in 2012. “It’s a pretty crazy community.”