On a vast expanse of land behind a commuter town just east of London, 108,000 newly installed solar panels glint in the sun, soaking up energy that will soon be transported through cables to the UK capital.

Ordinarily, the site, which is bigger than 28 football fields, would have been attractive to developers looking to build houses, which are in short supply in this part of the country. But the land parcel near South Ockendon, a half-hour train ride from central London, has lain barren for the past 25 years. Dig a few feet into the ground and you’ll find out why: The site sits atop a 5 million-ton trash heap that threatens to spew out poisonous methane if its seal is damaged.

Set to be one of the biggest solar parks in the UK when it comes online by next month, the project will help solve a space dilemma often faced by clean energy providers tasked with supplying power to big cities. Although population density increases the demand for cheaper and cleaner forms of electricity, it also creates a shortage of available land.

“You can’t do a lot with a closed landfill, there aren’t too many competing reuse options for it,” said Matthew Popkin, who works on a project to encourage renewables development on brownfield sites at the Rocky Mountain Institute, a Colorado-based think tank. “And unfortunately, but understandably, there is a landfill of some kind in most communities across the world because of the trash we have generated.”

The farm has capacity to generate 58.8 megawatts of electricity, enough to power about 17,000 homes, pushing the UK a notch closer to its goal of increasing solar capacity nearly fivefold by 2035. But completing the project hasn’t been easy. While installing solar on disused trash heaps may be a logical solution to a space issue, it poses technical challenges that pushed up the price of the project.

The panels had to be fixed in batches to ballasted bases made of concrete to prevent the foundations, which can normally be dug as much as 3 meters into the ground, from piercing through the sealing of the landfill site. Some had to be installed with adjustable legs in case the ground moves over time as the trash underneath decomposes.

The project costs roughly £850,000 ($1.1 million) per megawatt of power it will produce, around 5% more than a solar farm installed on ordinary land, according to Eamonn Medley, director of business development at NTR Plc, the renewables investment manager behind the project. Similar ventures have been undertaken in other parts of the world, such as the US and southern Brazil, and sometimes the cost can be as much as 15% higher, depending on the state of the landfill, freight and material prices.

Like for many other renewables projects, inflation has also posed major challenges, though Medley and his team were able to push on without delaying the installation thanks in part to a contract to sell all the energy generated for the first 10 years to BT Group Plc. After that, the site will sell the energy produced at wholesale market prices.

“We saw the turbulence in module pricing, in the steel and in the transport costs,” Medley said during a tour of the park last month. “We also saw it in the wholesale price and in the exchange rates — there was inflation in everything.”

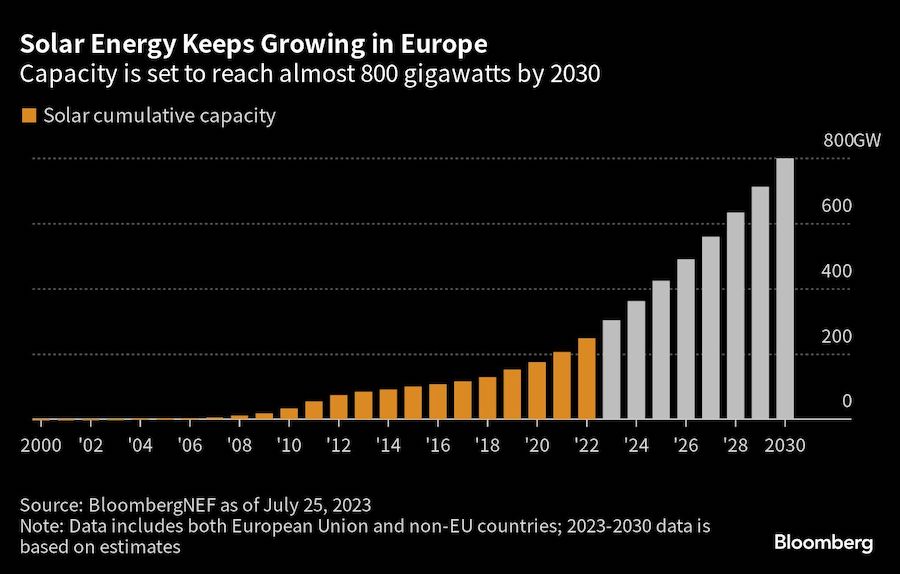

The cost of materials is now starting to come down thanks to an oversupply of solar components from China that flooded the market, crashing spot prices to record-low levels, according to BloombergNEF data. That, coupled with how viable it has become to build on wasteland can prove to be a boon for developers, potentially unleashing a new wave of projects. BloombergNEF expects over two gigawatts to be installed in the UK this year, up from 1.2 gigawatts in 2022.

Large-scale solar farms are usually built on disused land, but often that’s difficult to find near the big cities that need the electricity the most. The UK’s largest park — with 72 megawatts of capacity — is located in North Wales. An even bigger park is under construction near Faversham in Kent, just over 50 miles from London.

In the UK, many new renewables projects, especially those in remote locations, are also constrained by their lack of grid connection, with some facing a decade-long wait to be connected. That wasn’t a problem for Ockendon, which was purchased with a grid connection offer in place.

Transmission, distribution and proximity to electricity use are important factors when planning a solar project, according to Popkin from the Rocky Mountain Institute. “In most cases, landfill solar offers a win-win to reinvent these sites for future energy needs,” he said.

If it weren’t for the black plastic methane valves dotted among the solar panels on the Ockendon site, you wouldn’t know that you were walking over layer upon layer of rotting garbage. Vast landfill sites like this are present near every major city and often aren’t being used.

“The question is, can we achieve the returns that the market is looking for on renewables building on a landfill, where you have to spend more money than you would normally spend?” Medley said. “It’s hard, but it can be done.”