There’s a fight brewing in the lithium market, after a controversial forecast from Goldman Sachs Group analysts set off a backlash among some of the industry’s most prominent experts.

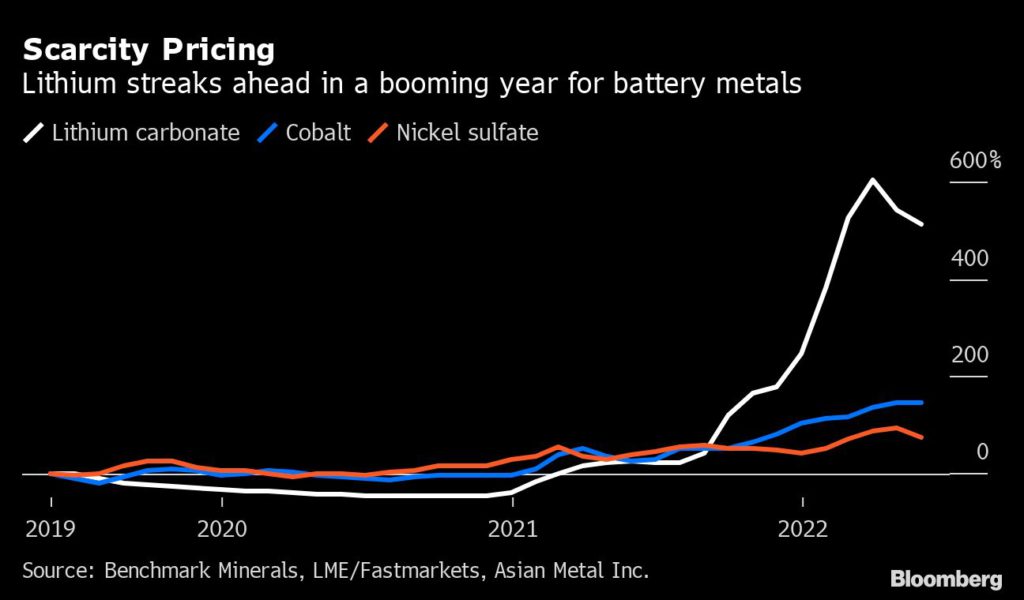

Lithium is a vital component of electric-vehicle batteries, which means the outlook for supply, demand and pricing is increasingly consequential. For years, a small group of niche consultants has dominated the conversation in a commodity that some say will become as important as oil in the coming century. Now, with prices surging and demand booming, they’re increasingly sharing the stage with Wall Street titans like Goldman.

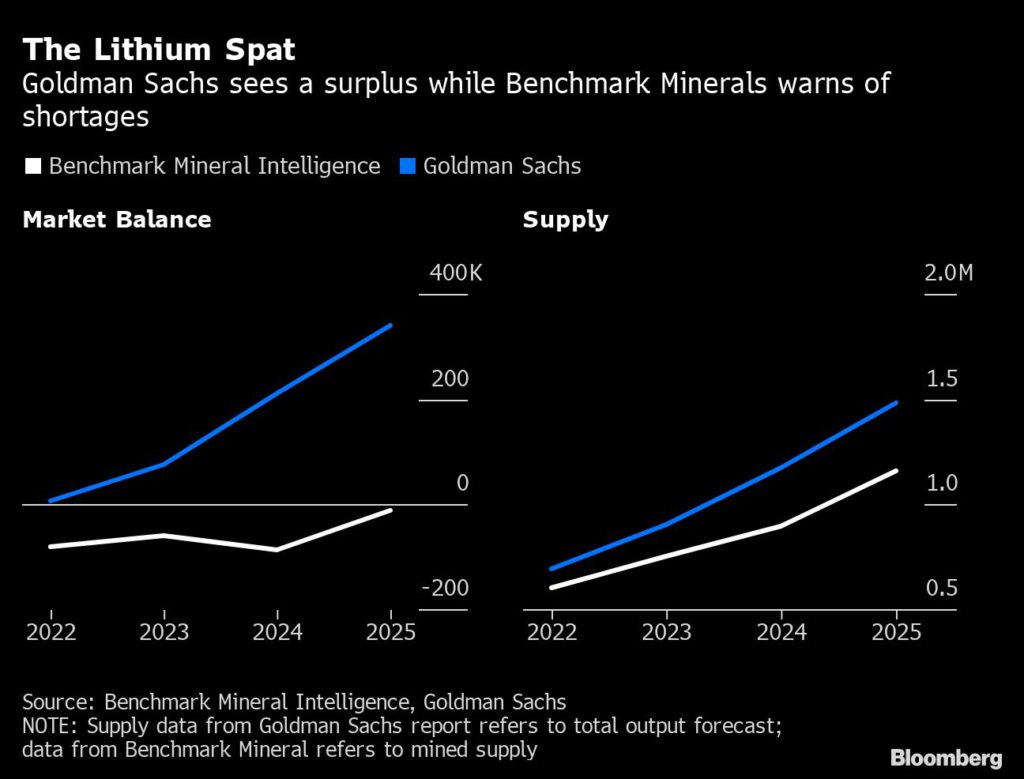

The bank made headlines when it warned that a searing rally in lithium will go into reverse this year as supply from unconventional new sources overwhelms demand. Credit Suisse Group AG also joined in predicting a correction. But specialists including London-based Benchmark Mineral Intelligence are loudly pushing back.

The rift matters because both groups play important roles in the burgeoning electric-vehicle industry. The niche consultancies offer tailored research to miners, battery-makers and car companies that guides decisions about whether to invest in new projects; Wall Street banks — and the investors that read their research — help determine whether they can afford to do so.

Benchmark disputes Goldman’s forecast that a flood of new production is on its way, and that prices will crater as a result. The consultancy still sees prices retreating from recent sky-high levels, but takes a more pessimistic view on the scale and timing of new supply. The mining industry is famously bad at hitting its production targets and lithium has added risks to due to the highly complex technical processes involved in making the final products used in battery packs, Benchmark says.

“You’ve got this additional hurdle arising because it’s not a commodity, it’s a specialty chemical,” Daisy Jennings-Gray, a senior price analyst at Benchmark, said by phone. “It’s a two-stage concern combining the traditional problems that the mining industry has faced with the additional challenges that a specialty chemical producer might face.”

The spat may seem trivial, but the stakes are high for those who rely on the forecasts, given lithium’s critical role in the electric-vehicle revolution and the wider fight against climate change.

If the deficits persist and prices spike further, it could cause car-makers’ margins to collapse, and potentially slow the mass roll-out of electric vehicles. But if prices slump, miners could scrap major new projects, setting the stage for even larger spikes and deeper deficits in the 2030s, when sales of electric vehicles will need to outstrip those of conventional cars if the industry is going to have a hope of hitting its net-zero targets.

“The lithium industry in its current form is very young, and so it’s difficult to say with confidence how responsive miners will be in bringing on new supply,” said Peter Hannah, a senior price development manager at Fastmarkets, a price reporting agency and industry consultancy. “A lot of it hinges on technology that we’ve never really seen before, and so there a lot of variables to consider, and each one could prove each of us wildly wrong, one way or another.”

Of course, disagreement among analysts is common in commodities markets, but the scale of the divergence is particularly acute in battery metals like lithium, where supply and demand are both growing at a breakneck pace. While a market like copper typically grows by 2%-4% a year, lithium analysts are anticipating growth of more than 20% for both supply and demand between 2021 and 2025.

Calculating error

That means minor differences in analysts’ assumptions — for example about the chemical composition of batteries or the timing of new mining expansions — can have a major impact on their supply-and-demand estimates. It’s an issue that’s cropping up in other battery metals like cobalt and nickel as well.

George Heppel, who developed models for battery metals demand at commodities consultancy CRU Group before joining BASF SE earlier this year, said in a LinkedIn post last month that a minor error in calculating nickel demand meant forecasts underestimated usage by about 30%. And others in the industry were doing the same.

“Several months after fixing my model, I was having lunch with a nickel analyst at an investment bank who was angrily complaining about how the nickel demand numbers being generated by the bank’s battery division were far too low. It was with much satisfaction that I was able to reveal the likely issue,” Heppel wrote.

In lithium, expert consultancies claim that the wayfarers from Wall Street are far more likely to overlook the nuances of the industry in carrying out their research. Joe Lowry, the founder of specialist advisory firm Global Lithium, has frequently taken to Twitter to call out perceived shortcomings in research by banks.

Matt Fernley, the London-based managing director at Battery Materials Review, an industry researcher, said the sellside reports are “massively over-estimating” the ease of adding new supply, and failing to consider the complexity of bringing new assets into production and the qualification requirements.

“The lithium industry needs to raise hundreds of billions of dollars of capital for expansion over the next 10-15 years,” he said. “A lot of that needs to come from equity and that’s going to be difficult if equity prices are depressed because of such reports.”