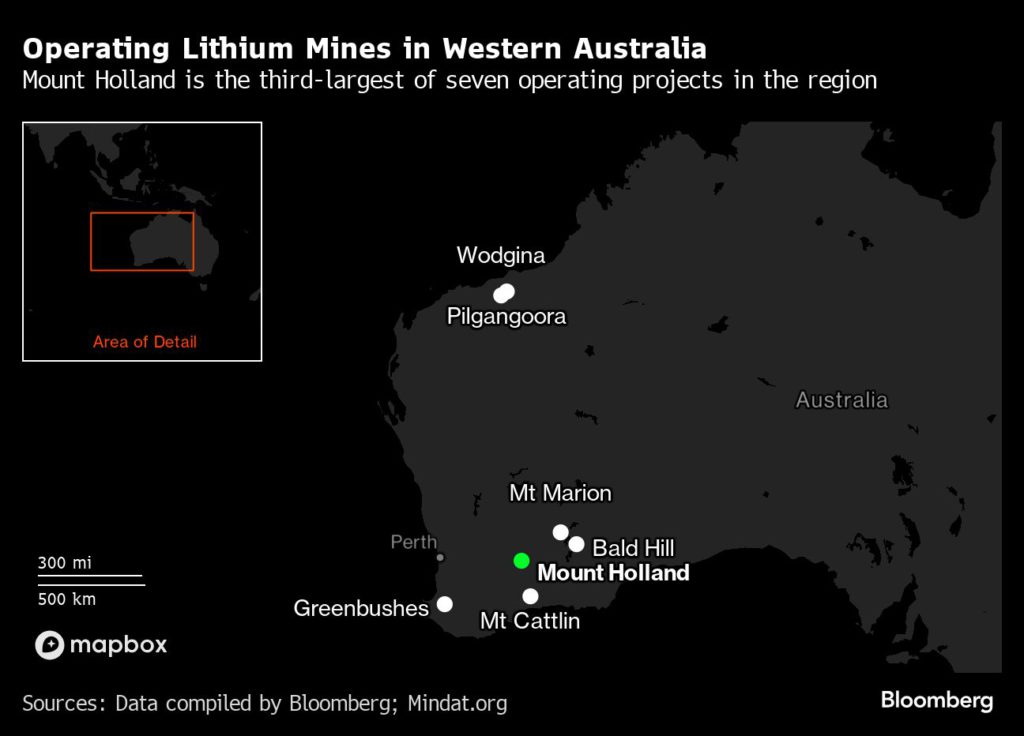

Against the arid, red dirt of the Australian Outback, the Mount Holland lithium mine emerges to approaching visitors as a colossal grey-tinged crater, with trucks the size of houses edging along its steep inclines.

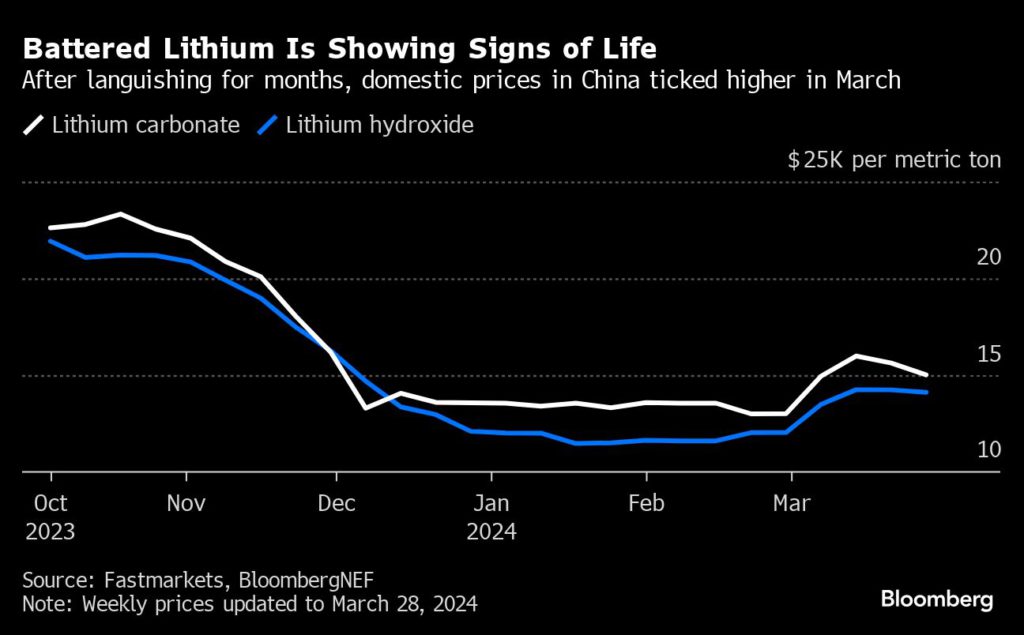

An expanding site at the heart of the world’s top lithium-producing region, the A$2.6 billion ($1.7 billion) operation is emblematic of the plentiful additional supply of the battery material currently weighing on global prices, much of it from this neighborhood. Despite bullish long term forecasts, the metal has been languishing near two-year lows as demand fails to keep pace.

But the sprawling mine is also a glimpse of the future for Western Australia, or of what this vast region, defined for decades by the demands of China’s steel industry, hopes will be a new, greener stage of development. The battery ingredient still makes up a sliver of exports but its prospects have already attracted attention — and billions of dollars of investment — from some of the region’s biggest and brashest mining names, from Gina Rinehart to Chris Ellison’s Mineral Resources Ltd.

Owned by mining giant Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile and Australian conglomerate Wesfarmers Ltd., Mount Holland is one of the largest operations set up in Western Australia over recent years. A processing plant opened last month and a refinery will follow next year, eventually producing enough lithium hydroxide to power close to one million new electric vehicles every year for half a century.

The catch is that the plant’s backers are expanding into a glut that has already forced some to hit the pause button, and risk extending a downturn that has battered the industry.

In part, that’s an expression of confidence in an eventual recovery in demand. It’s also a bet on the role resource-rich Western Australia will play, not only in mining, but in efforts down the supply chain to counter Beijing’s near-monopoly in processing as the capacity to refine lithium-bearing spodumene into lithium chemicals needed in batteries expands.

The International Energy Agency forecasts lithium demand will increase forty-fold from 2020-2021 levels over the next decade and a half, thanks to battery and electric-vehicle demand alone, requiring dozens of extra Mount Hollands.

“It was an adventure for us at the beginning, but now it is the future,” Ricardo Ramos, chief executive officer of SQM, the world’s second-largest lithium producer. SQM gets most of its production from Chile, but its extraction contract there expires in 2030, leaving the future uncertain.

“I would love to have ten more Mount Hollands in Australia as we speak today — one is not enough,” Ramos said.

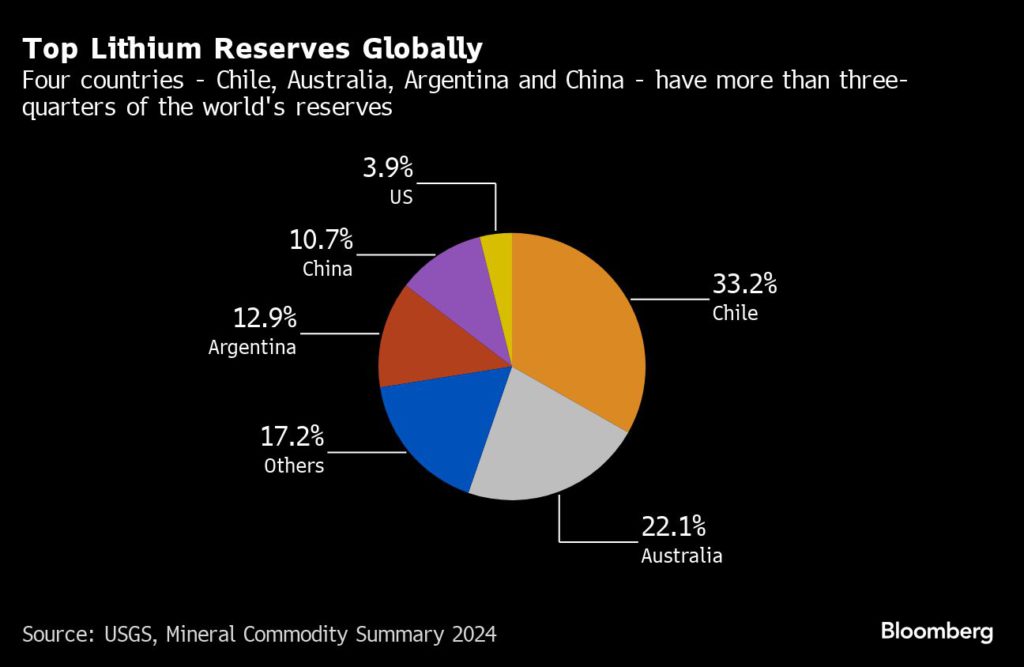

Chile has by far the world’s most expansive natural endowment, with its mineral-rich salt flats. But outside Latin America’s Lithium Triangle, which also includes Argentina and Bolivia, it’s Australia that has the world’s most significant reserves of the metal, a vital component for the rechargeable batteries at the heart of the electric revolution.

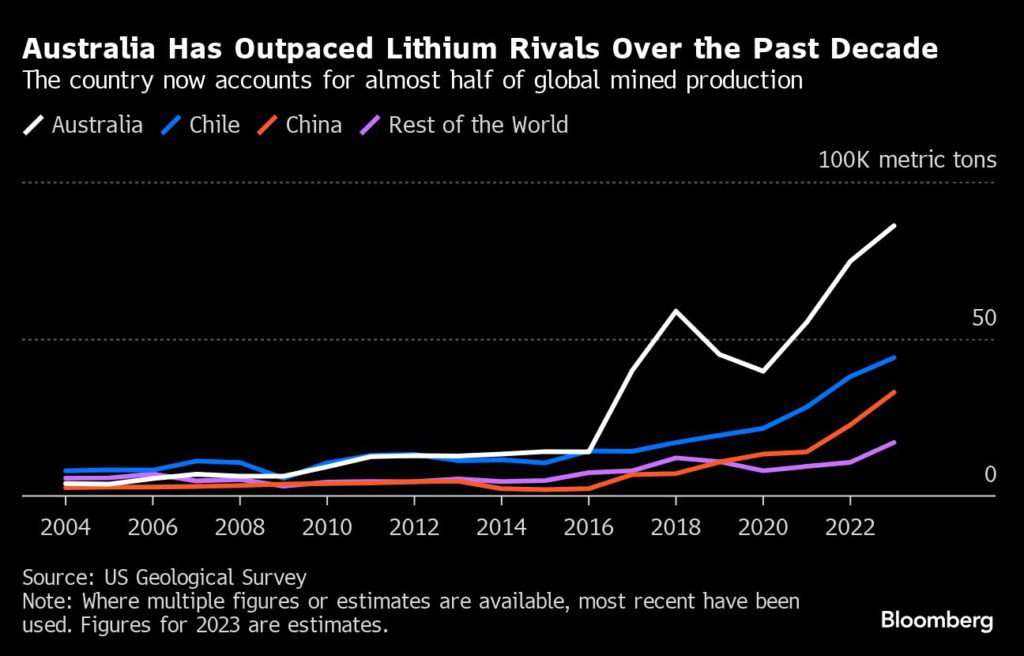

The ability to extract lithium swiftly from hard rock resources, plus existing infrastructure, means it has already seen something of a development boom. In 2016, there was one producing lithium mine in Western Australia. Today, there are seven. A country that accounted for roughly a sixth of supply in 2000 now makes up almost half of global mined production, close to double Chile’s output — significant even if China still dominates refining capacity.

In the context of a mining history that dates back close to two centuries, the enthusiasm for the ultra-light metal here is relatively new. Until recently, Western Australia’s heftiest investments were focused on bigger earners, like iron ore, the ingredient that underpins the world’s largest miners. Lithium was used to treat bipolar disorder and even harden glass for perfume bottles.

“It used to be so difficult to get a sale that we had a bell in the office. We used to ring the bell when we’d secure a sale and the whole office would cheer,” Dale Henderson, CEO of lithium producer Pilbara Minerals Ltd, said.

“We’d ring the site and say ‘turn the plant back on, we’ve got a sale’. That was only a few short years ago.”

Like others here, Henderson sees the hesitation among investors and some developers. But he argues that the relative youth of the lithium market means last year’s price plunge and flattening electric-vehicle demand should be seen as growing pains.

Certainly the billionaires who made fortunes in iron ore and need a new bet for the future have also continued to pile into the metals of the energy transition. Rinehart’s major known lithium investments alone, with her company Hancock Prospecting, are worth close to $1 billion at current market prices — before adding copper, rare earths and more.

Still, the question is whether veteran producers, tycoons and indeed Western Australia can parlay previous experience in bulk materials into the ability to mine, process and move down the battery supply chain, making the most of free-trade agreements with the US and other markets to provide the country’s economy with another leg of growth.

All while getting around major hurdles, including a higher carbon footprint than producers like Chile, given the energy intensity of hard-rock processing, and technical challenges around the production of lithium hydroxide that have hampered even heavyweight Albemarle Corp, hit by post-pandemic delays and cost increases. Australia’s first lithium refinery at Kwinana, a joint venture between Tianqi Lithium Corp. and IGO Ltd., began production in 2021 and has since struggled to achieve expected output volumes, while plans for expansion were put on hold.

From the very earliest days, mining has been woven into the fabric of Western Australia, a region roughly the size of Western Europe with a population half that of tiny Singapore. The industry dates back to a gold rush in the 19th century, but it was China’s economic awakening that created a steel and iron ore boom so expansive that it helped the country’s economy to sidestep the global financial crisis and cushion the impact of the pandemic.

China’s appetite for vast construction projects is now cooling, steel producers are under pressure to clean up a sector that accounts for at least 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions and earnings from Australia’s iron ore are expected to fall — from A$136 billion this fiscal year to just A$83 billion by 2028-29, according to government forecasts.

Lithium is not going to fill that gap anytime soon. Even in 2028-29, exports are forecast at just over A$9 billion.

To expand the impact of the lithium boom and the benefits in export revenue and job creation, Western Australia will need to extend its geological advantage and double down on other battery materials, including copper, all with some policy assistance. After its critical minerals strategy last year, Australia’s government says it is planning further measures to support downstream processing.

Citi analyst Kate McCutcheon argues Australia has advantages — plentiful hard-rock lithium resources, the potential to benefit from a price premium for suppliers compliant with the US Inflation Reduction Act and the green prize of keeping more processing close to home.

But there are still challenges, including high costs and energy supply, not to mention the need to manage lithium hydroxide’s limited shelf life — typically it starts to degrade after six months — short of expanding further into battery production.

“You’re competing against other countries which in some sectors are offering attractive tax holidays, lower labor and energy. Downstream projects to date outside of China have proven much harder to operate than expected, with costs a lot higher,” McCutcheon said.

Back at Mount Holland, Western Australian Premier Roger Cook points out that last year the rise of lithium in the mining region brought in more royalties than the gold fields. The state, and Australia, will be here for the next act.

“Let’s not lose perspective,” he said, speaking over the crunching of crushed ore. “Demand is still growing and we will be here to meet it.”