Obi, among hundreds of scattered spice islands in the Maluku archipelago, is an unlikely spot for a metal market convulsion. Only the northern part of this island gets power from the state utility. It’s home mostly to fishermen and coconut farmers.

Harita Nickel’s sprawling complex of processing machinery and conveyor belts tells a different story. One of a new breed of nickel producers, backed by Chinese know-how and cash, it’s using the latest generation of a method known as high-pressure acid leaching, or HPAL, to turn Indonesia’s low-grade ore into metal fit to power a Tesla car.

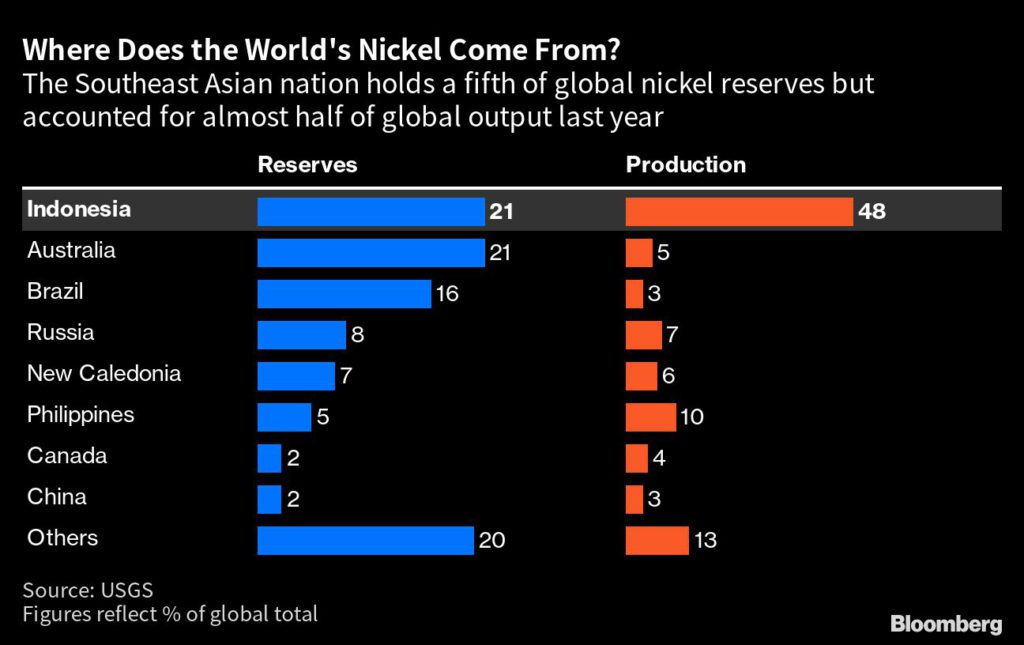

Success would have dramatic implications far beyond the Southeast Asian nation, where President Joko Widodo has put the world’s largest nickel reserves at the forefront of an ambitious plan to transform the economy into a key player in the electric-vehicle supply chain.

The new HPAL projects, and the surge of inexpensive metal from a country whose deposits have long been unloved by major producers, could push the market into oversupply. Within two years, Indonesia could supply 65% of the world’s nickel, up from 30% in 2020, Macquarie Group Ltd. estimates. With so much metal outside the London Metal Exchange and the Shanghai exchange, Indonesia threatens to upend even nickel pricing benchmarks.

And this giant chemistry experiment comes with environmental consequences. Compared with more traditional methods, HPAL produces nearly double the amount of tailings that need to be treated and stored, raising the risk of severe contamination as all sides rush to capture battery spoils. The power to process this green ingredient still mostly comes from coal.

Two years ago, workers in Obi — two flights and a three-hour ferry ride from Jakarta — rolled a nearly 1,000-ton pressure cooker-like machine down a red dirt path.

A team filled it with ore and sulfuric acid and waited. A liquid emerged in a startling blue-green: the color of oxidized nickel and confirmation of a dramatic change in the world’s production of a key metal for batteries. Harita Nickel, working with Ningbo Lygend Mining Co., had become the first to turn ore into mixed hydroxide precipitate or MHP, a form of nickel that can be further refined into batteries. It has since become the first in Indonesia to process that intermediate product into nickel sulfate, another step up in the value chain.

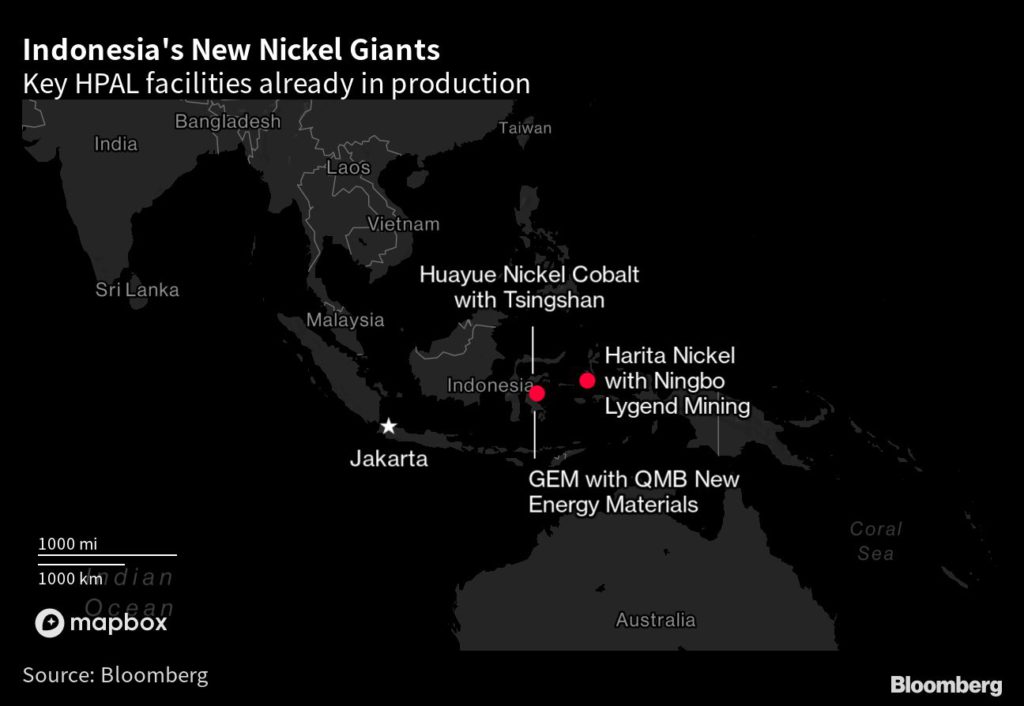

The Obi island operation is now one of three producing HPAL outfits, and more are in the pipeline, with nearly $20 billion of further projects announced. Next month, Harita plans to go public on the Jakarta exchange. Shares have been priced at the top of the range, giving it a market value of more than $5 billion.

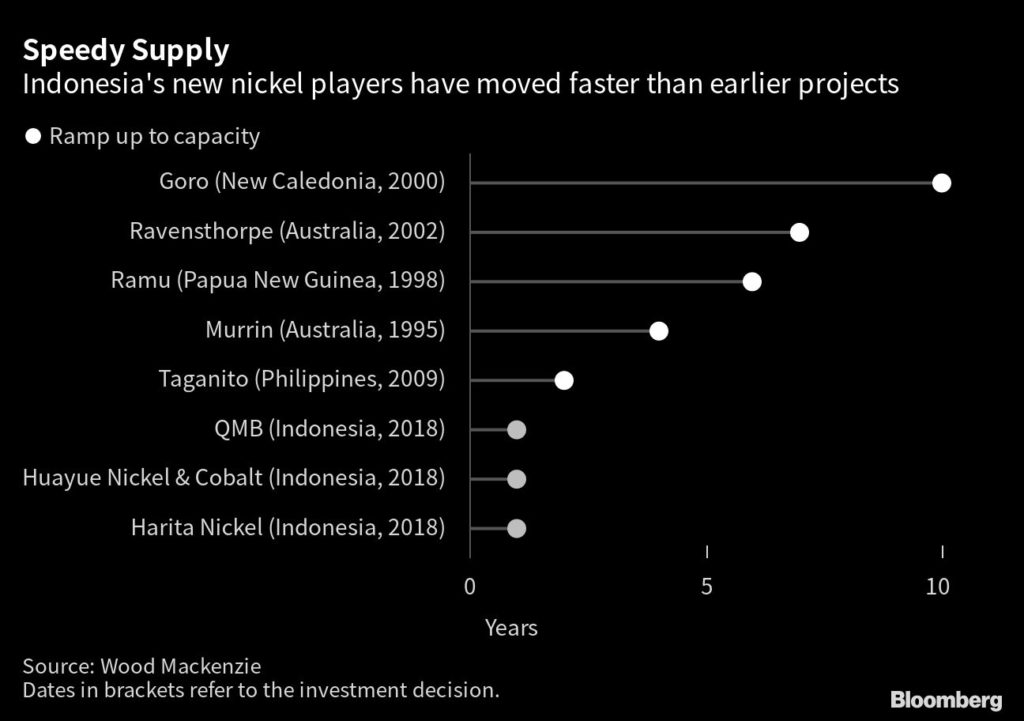

Until this new generation, HPAL was known mostly for cost overruns and delays. Mining giant Vale SA experienced both before opening its plant in Goro, New Caledonia, in 2010; it’s never produced beyond 70% capacity. Chemical spills and protests by pro-independence activists in the French territory disrupted production, and Vale eventually sold its stake.

This time, Harita says, is different — thanks to China.

“China has done with HPAL in Indonesia what they did with nickel pig iron in China 20 years ago,” said Angela Durrant, principal nickel analyst at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “It’s like teaching a child something new again and again — and suddenly they get it. Then they run with it, they catapult onward. This is what Indonesia is doing with China’s technology.”

Apart from Harita’s operation, other new arrivals include a venture combining Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Co., CMOC Group and Tsingshan Holding Group Co. — Huayue Nickel Cobalt — which has built a $1.6 billion plant on the island of Sulawesi. GEM Co. has backed a separate $1.6 billion facility nearby, QMB New Energy Materials, with Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd’s Brunp unit and Tsingshan again.

The world’s largest nickel producer, Tsingshan had a prominent role in last year’s historic market squeeze. But it’s also known for its large-scale use of low-cost nickel pig iron that disrupted the stainless steel supply chain two decades ago. It then shocked the market again in 2018 by announcing a $700 million plan to produce battery-grade nickel in Indonesia at breakneck speed. It missed initial targets but still beat legacy rivals by years.

The results of the Indonesian revolution are visible. Mining majors producing high-end nickel have traditionally focused on sulfide ores, but today, low-grade ores that were once fit only for stainless steel are now suitable for wider use. HPAL uses material with as little as 0.9% nickel, and the cost — crucially — is manageable. It costs Harita $5,225 for a ton of nickel content using HPAL, 48% less than with traditional electric-furnace smelters, according to AME Research.

The process also yields a cobalt bonus, another key material for batteries, and the spate of investment has made Indonesia the largest source of cobalt outside of Africa.

Harita Nickel, also known as Trimegah Bangun Persada, says it learned from an HPAL plant in neighboring Papua New Guinea, which took six years to reach capacity.

The company took the same formula, including the design by China ENFI Engineering Corp., and made improvements. It patented a more efficient way to remove chrome from ore, reducing the need for sulfuric acid, which makes up one-third of the cost of HPAL.

It took one year and $1.5 billion for Harita to be fully operational. It’s since been producing at 110% of its target capacity.

Speed and scale have brought political challenges and operational concerns, with rising scrutiny on critical mineral supplies and a technology dependent on expensive, inflation-sensitive ingredients. But the environmental cost may be the biggest headache: A technology so vital to the green energy transition generates vast quantities of waste.

Harita presses the water out of its waste slurry then stacks the dry soil in former mining sites, but there’s not enough space. Its mines contain enough laterite ores to keep the HPAL facility busy for 17 years. Its dry-stacking area could accommodate just six years worth of waste, and even that’s optimistic in a high-rainfall tropical region, says Wood Mackenzie’s Durrant: “There is no such thing as dry stacking in a wet environment.”

The company proposes building a dam for tailings, bypassing the dry-pressing machine and letting the sun dry the waste slurry. But that presents its own problems. The troubled Goro mine in New Caledonia curtailed output after a leak from its tailings dam in November. And there are few easy alternatives — Ramu, the plant that inspired Harita, disposes of its tailings in the sea, a controversial practice banned in Indonesia, where seas tend to be shallow.

Harita has already faced a taste of those challenges. Reports of pollution prompted the company to build more than 34 hectares of sediment ponds to prevent mining runoff from reaching the ocean. It fenced off a spring after employees unwittingly contaminated the source of drinking water with a cancer-causing chemical. And a plan to relocate a nearby village to a purpose-built housing complex remains controversial.

“If money wasn’t an issue then companies would employ dry stacking — that is the best approach for Indonesia. But it’s very costly,” said Allan Ray Restauro, metals and mining analyst at BloombergNEF. There is a risk, he added, that Jakarta will withhold environmental permits if the waste issue remains unresolved. “This could lead to considerable delays.”

When Indonesia decided against granting permits for deep-sea tailing disposal in 2021, the policy U-turn led to delays to several nickel projects in Sulawesi.

So far, the local economy is reaping the gains from the nickel boom. North Maluku expanded 23% last year, four times the country’s growth rate. Jokowi has hailed the province as a successful example of his commodities policy.

Inside Harita’s plant in Obi, Rivan Lie points to a pool collecting liquid emerging from HPAL machinery. Suspended in the water, the MHP looks like moss. From there, it will be dry-pressed into a different kind of green. “That’s the nickel,” said Lie, charged with the plant’s human resources. “That’s the money.”