There’s a big push underway to increase the lifespan of lithium-ion batteries powering EVs on the road today. By law, in the US, these cells must be able to hold 80% of their original full charge after eight years of operation.

However, many industry experts believe we need batteries that last decades—so that once they’re no longer robust enough for use in EVs, we can put them to use in “second-life applications”—such as bundling them together to store wind and solar energy to power the electrical grid.

Researchers from Dalhousie University used the Canadian Light Source (CLS) at the University of Saskatchewan to analyze a new type of lithium-ion battery material—called a single-crystal electrode—that’s been charging and discharging non-stop in a Halifax lab for more than six years.

It lasted more than 20,000 cycles before it hit the 80% capacity cutoff. That translates to driving a jaw-dropping 8 million kms. As part of the study, the researchers compared the new type of battery—which has only recently come to market—to a regular lithium-ion battery that lasted 2,400 cycles before it reached the 80% cutoff.

“The main focus of our research was to understand how damage and fatigue inside a battery progresses over time, and how we can prevent it,” says Toby Bond, a senior scientist at the CLS, who conducted the research for his Ph.D., under the supervision of Professor Jeff Dahn, Professor Emeritus and Principal Investigator (NSERC/Tesla Canada/Dalhousie Alliance Grant) at Dalhousie University.

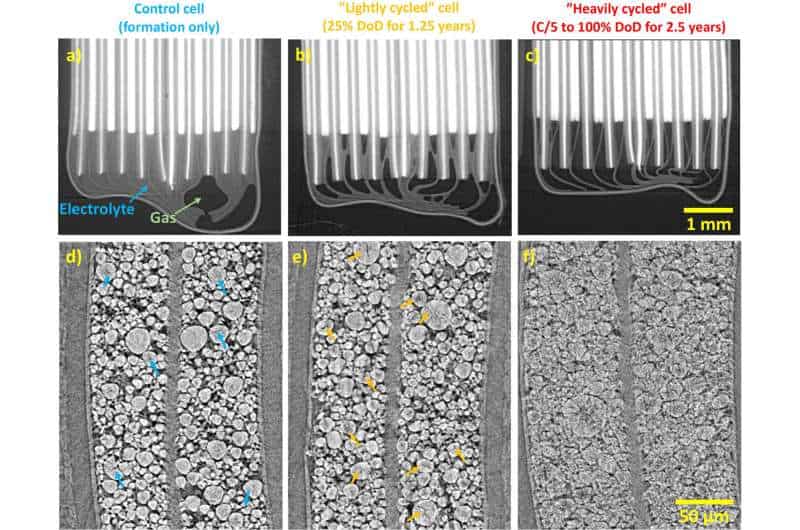

Things got very interesting, he says, when the scientists used the ultrabright synchrotron light to peer inside the two batteries. When they looked at the inner workings of the regular lithium-ion battery, they saw an extensive amount of microscopic cracking in the electrode material, caused by repeated charging and discharging. The lithium, he explains, actually forces the atoms in the battery material apart and causes expansion and contraction of the material.

“Eventually, there were so many cracks that the electrode was essentially pulverized.”

However, when the researchers looked at the single crystal electrode battery, they saw next to no evidence of this mechanical stress. “In our images, it looked very much like a brand-new cell. We could almost not tell the difference.”

Bond attributes the near absence of degradation in the new style battery to the difference in the shape and behavior of the particles that make up the battery electrodes. In the regular battery, the battery electrodes are made up of tiny particles up to 50 times smaller than the width of a hair.

If you zoom in on these particles, they are composed of even tinier crystals that are bunched together like snowflakes in a snowball. The single crystal is, as its name implies, one big crystal: it’s more like an ice cube. “If you have a snowball in one hand, and an ice cube in the other, it’s a lot easier to crush the snowball,” says Bond. “The ice cube is much more resistant to mechanical stress and strain.”

While researchers have for some time known that this new battery type resists the micro cracking that lithium-ion batteries are so susceptible to, this is the first time anyone has studied a cell that’s been cycled for so long. “The great thing about doing this kind of measurement at a synchrotron is we can actually look at this at a microscopic level without having to take the cell apart. Once we cycle a cell for six years, you really don’t want to take it apart—it’s very precious, it’s very valuable to us, with so much information contained within it.”

Bond says what’s most exciting about the research is that it suggests we may be near the point where the battery is no longer the limiting component in an EV—as it may outlast the other parts of the car. “We really need these vehicles to last as long as possible, because the longer you drive them, the better its improvement on the carbon footprint is,” says Bond. As well, if battery packs can outlast the vehicle, you can use them for mass energy storage—where the energy density that’s critical for powering an EV—doesn’t matter as much.

The new batteries are already being produced commercially, says Bond, and their use should ramp up significantly within the next couple of years. “I think work like this just helps underscore how reliable they are, and it should help companies that are manufacturing and using these batteries to plan for the long term.”

The research is published in the Journal of The Electrochemical Society.