By incorporating manganese into an all-inorganic perovskite solar cell, scientists have increased its efficiency and stability while keeping manufacturing costs low.

A research group in Japan has developed a material for creating more stable and efficient solar cells at low cost. They published their work in Advanced Energy Materials. Most solar cells are made of silicon panels which are expensive to produce.

Hence, scientists have been working on alternatives made from much cheaper perovskite structures. True perovskite, a mineral found in the earth, is composed of calcium, titanium and oxygen in a specific molecular arrangement. Materials with that same crystal structure are called perovskite structures.

Perovskite structures work well as the light-harvesting active layer of a solar cell because they absorb light efficiently. They can also be integrated into devices using relatively simple equipment. However, perovskite structures are often very unstable, deteriorating on exposure to heat.

This has hindered their commercial potential. The Energy Materials and Surface Sciences Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), Japan, led by Professor Qi Yabing, has developed devices using a new perovskite material that is stable, efficient and relatively cheap to produce. This material has several key features.

First, it is completely inorganic—an important distinction because organic components are usually not thermostable and degrade under heat. Since solar cells can get very hot in the sun, heat stability is crucial. By replacing the organic parts with inorganic materials, the researchers made the perovskite solar cells much more stable.

“The solar cells are almost unchanged after exposure to light for 300 hours,” said Dr. Liu Zonghao of OIST, who is a co-author of the paper. While all-inorganic perovskite solar cells tend to have lower light absorption than organic-inorganic hybrids, the OIST researchers doped their new cells with manganese. Manganese changes the crystal structure of the material, boosting its light harvesting capacity.

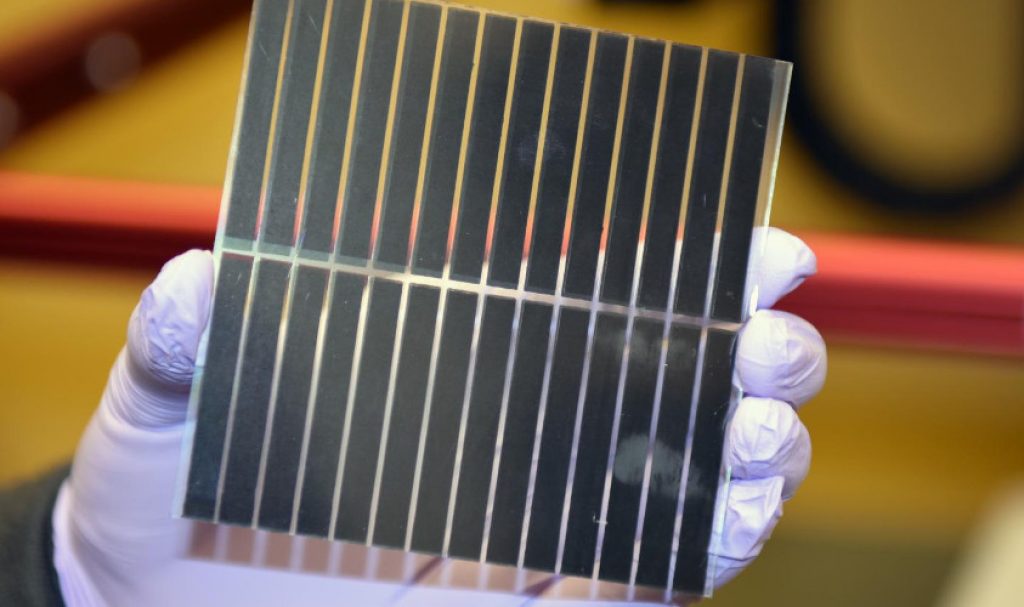

“Just like when you add salt to a dish to change its flavor, when we add manganese, it changes the properties of the solar cell,” said Liu. Finally, in these solar cells, the electrodes that transport current between the solar cells and external wires are made of carbon, rather than the usual gold. Such electrodes are significantly cheaper and easier to produce, in part because they can be printed directly onto the solar cells.

Fabricating gold electrodes, on the other hand, requires high temperatures and specialist equipment such as a vacuum chamber. The researchers intend to continue to improve the efficiency and durability of their solar cells, and are also developing the process of fabricating them on a commercial scale. Given how quickly the technology has developed since the first perovskite solar cell was reported in 2009, the future for these new cells looks bright.