For those of us working on the future of vehicles and energy, this is a fascinating time. Cities are at the root of clean vehicle adoption, and city mayors can have more near-term influence over automotive product offerings than national and international regulators. Original plans to ban diesel engine vehicles in Paris by 2030 already have given way to more stringent proposals. Rome, Madrid, Athens and Mexico City are also lining up to push out diesel vehicles by 2025.

These cities do not constitute a dominant share of the global, European or even national car markets; but they and cities following this trend are big enough to matter. Consumer uncertainty has set in and diesel car sales are in decline across all main markets; 17 percent down in the U.K. during 2017, for example. But clean air and greenhouse gas challenges mean that not just diesel is under pressure, and the future of all fossil-fuelled internal combustion engines is blurry. Governments and vehicle manufacturers are signaling that new cars built from 2020 onwards into the future will be electric.

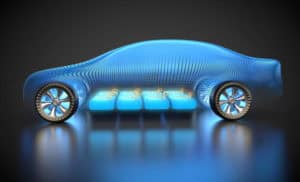

Current wisdom holds that the engine’s loss will be the battery’s gain. Manufacturers are knocking over barriers previously thought insurmountable, and consumers and operators are embracing plug-in vehicles in major cities worldwide. Job done? We think not yet. It is worth examining the overall picture, and cars separately from other vehicles to understand why.

For cars, battery size matters

For cars in major cities, a battery electric vehicle [BEV] with a modest range could meet the needs for most journeys, and so would be the logical choice for trips around town. However, we see potential drawbacks. First, private cars are not bought for average or even 90 percent of journeys; consumers desire a car to meet the extremes and for single-car households that may include weekends out of town and holidays.

Secondly, BEVs are most relevant in dense urban areas, yet this is also where recharging at home is most challenging. For example, 43 percent of U.K. households have no off-street parking — a higher proportion inevitably applies in cities. Building genuinely cost-effective charging networks is proving tough, and the payment and maintenance business models have not yet matured.

Range and recharging drawbacks can be mitigated to some extent by larger capacity batteries, but this creates its own expensive knock-on. Even as battery costs tumble, a compact BEV with, say, a 100-mile range is still more expensive than its petrol engine equivalent. Subsidies mask this, for as long as governments can bear them. Total cost of ownership also tips the field back in the BEV’s favor somewhat, but for vehicles that do low mileages the case is weaker and depreciation is proving an Achilles heel for many BEVs.

Plug-in vehicles will have their day, but their success depends on something other than bigger batteries to deal with range and recharging challenges. A widespread functioning recharging infrastructure is important, particularly “fast” (7-22kW) and “rapid” (above 22kW) chargers which can provide useful range in minutes rather than hours. An alternative is some form of on-board range-extension device, whether an engine (optional in the BMW i3 for example) or potentially a fuel cell (a Mercedes GLC version will be launched this year). The latter’s obvious advantage is zero emissions in all modes, combined with an inbuilt insurance option against sparse hydrogen refueling and electric recharging points.

Commercial vehicles and buses are challenged by high use

Rationally minded fleet operators look for the lowest total cost to deliver an outcome. Battery EVs are part of the solution set for vans and buses that need guaranteed urban access in zero emission zones, high reliability and consumer acceptance. However, drawbacks exist here, too. More range implies heavier and bulkier batteries which reduce vehicle carrying capacity, exceed weight limits for bridges and even damage road surfaces.

Also, most fleet vehicles are heavily used, meaning that the window for recharging (usually at night) is narrow. While this can be planned for, the combined load on the power network is huge. Uncontrolled charging of a 40 battery bus fleet amounts to over 2MW and even with smart charging a new connection of around 1MW is required. Such connections are often very hard to secure near congested depots, and larger fleets may require their own substation.

These problems can be alleviated by frequent top-ups (“opportunity charging”) at bus stops and fast-charging points for commercial vehicles. Inductive charging pads in the road would make this even more convenient, but the upheaval and cost is not trivial. Another way to mitigate the charging challenge is on-board range extension, bringing engines and fuel cells into the picture, as for cars.

If only there were a zero-emission fuel

Battery vehicles undoubtedly will take a greater share of private car and commercial vehicle markets, but their rise will depend upon fast charging, opportunity charging, smart charging and ever-lower battery costs. Cities will help, with their push to eliminate fossil fuelled vehicles from their centers. In the meantime, other options will continue to be developed, notably plug-in hybrids in the near term, and hydrogen.

Although plug-in vehicles readily can be deployed today using familiar infrastructure, the challenges set in as uptake increases, as described above. The inverse applies to hydrogen vehicles, whose infrastructure is costly to establish but easier and cheaper to scale up incrementally.

Combined with hydrogen’s ability to fully refuel in minutes, provide zero emissions, act as a store for renewable electricity and even substitute natural gas for heating, the case for this fuel is strengthening. New research by KPMG reveals that most senior global automotive executives believe that BEVs will struggle due to recharging, and that fuel cell vehicles will provide the real breakthrough for electric mobility.

Importantly, however, we do not see an either-or choice, and find the strident assertions of some protagonists both unhelpful and misleading. Hydrogen fuel cell range-extended battery cars and vans combine the benefits of both energy types. Fuel cell buses and trucks fit well where use and range are paramount, batteries where there is more leeway. Battery cars already prove attractive for customers who can live with a short range vehicle or seek performance with less regard to cost.

Ultimately, city authorities need not and should not pick a technology winner, so it is worth making sure that the push for low emissions does not focus solely on one type of “electric” vehicle.