The company behind an industrial park in central Indonesia that is becoming a nickel production powerhouse says it is implementing measures to address growing environmental concerns over production of the commodity, a key component of stainless steel and batteries for electric vehicles.

The Morowali industrial park, located in the town of the same name, covers over 3,000 hectares on the eastern part of the island of Sulawesi. It’s about to unleash a torrent of new nickel supply that would push the market into a deeper surplus this year, but scrutiny from industry consultants and environmental groups is mounting around the nation’s heavy use of coal-fired power and waste-disposal plans.

Hamid Mina, the managing director of PT Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park, said the company is taking active steps to mitigate the environmental impact of the complex’s operations.

“Our next five years will be focused more on a ‘green’ industry,” said Mina. “Industry always has pollution. But the pollution has to be controlled and follows the government rule. That’s very important.”

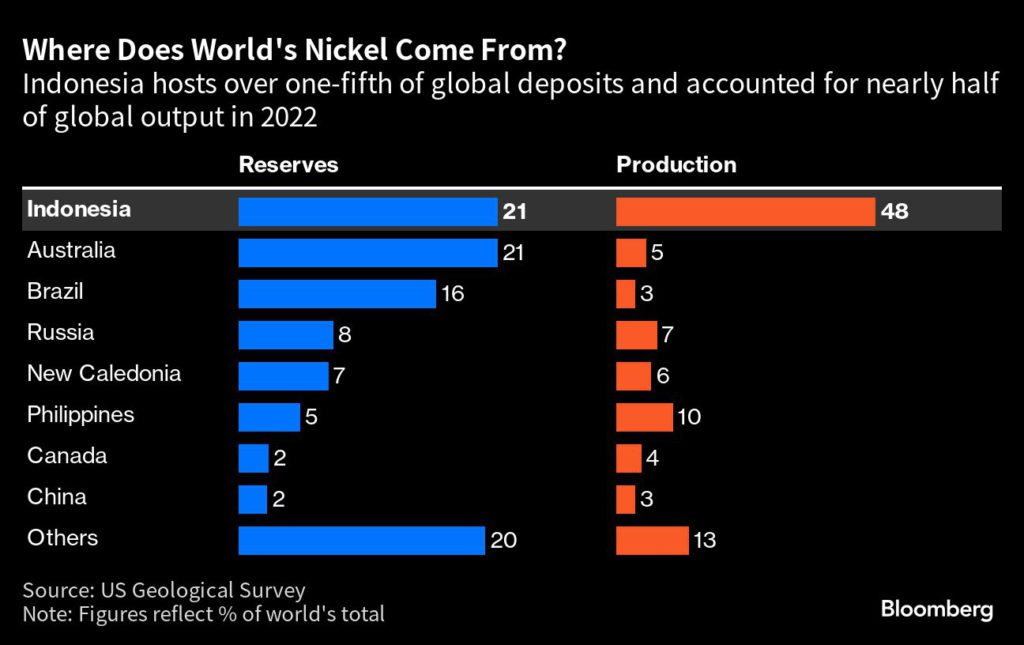

Indonesia is a major producer of nickel and could contribute over 60% of the world’s nickel supply by the end of the decade, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. But nickel production in Indonesia is particularly carbon intensive — every ton of the metal-equivalent produced emits an average of 58.6 tons of carbon-dioxide-equivalent compared to the global average of 48 tons, data from Skarn Associates show.

Among plans to lower the carbon footprint in the complex is the construction of solar panels of as much as 500 megawatts, Mina said. The park aims to invest $63 million for the first phase of 100 megawatts of panels, which it says will be able to generate 180 million kilowatt-hours of power a year. That can translate to enough electricity for about 166,000 Indonesians.

Skarn chief executive officer Mark Fellows, however, said that implementing renewable energy in Indonesia is “tricky” because of reasons including cloud cover and low wind potential.

IMIP, backed by mining company BintangDelapan Group and China’s Tsingshan Holding Group — the world’s biggest stainless steel producer that was also at the center of a historic market squeeze in 2022 — was formed in 2013. Over 50 companies later invested in the industrial park, including GEM Co. and a unit of the world’s largest battery manufacturer Contemporary Amperex Technology Co.

The complex is also facilitating the construction of about 50 kilometers (31 miles) of pipes to pump slurry directly from mines to the factory to reduce the use of trucks, Mina said, and IMIP is also considering introducing electric trucks in the park.

Skarn’s Fellows, however, said that emissions from trucks account only for a “very small portion compared to the coal-dependent” production process of nickel at the mine.

Morowali, which was mainly a fishing town just a decade ago, is at the heart of Indonesia’s economic boom and rose to global significance in the nickel industry after the country imposed an export ban on nickel ore in 2019, as the country moves to reduce its reliance on exporting mineral resources and invest more in higher-value downstream facilities.

More than $22 billion has been invested in the industrial park as of June, compared to $6.7 billion in 2019, according to IMIP.

President Joko Widodo is also hoping to take on a bigger role in the global EV-battery supply chain. The country has been courting investment from automakers, and a team from Tesla Inc. visited Morowali last year, IMIP said.

In terms of waste management, IMIP currently has nearly 600 hectares of land dedicated to dry-stacking, a method of treating tailings, a by-product of mining, by drying, compacting and backfilling them. More areas may be allocated for that if an expansion plan of the park to about 6,000 hectares is approved, Mina said.

However, dry-stacking is challenging in a country that has high rainfall and regular seismic activity, according to Harry Fisher and Bruna Grossl from Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. In the longer term, space and increased haulage distances are other issues, they said, adding that the Indonesian nickel industry must consider ESG aspects as it grows and “becomes increasingly important to the battery supply chain.”