The European Union has set targets to dig up, recycle and refine lithium, cobalt and other metals it needs for its green transition, but a shortage of new money, crippling energy costs and local opposition could put them beyond reach.

The bloc will likely need to find ways to trim demand, find substitute materials and forge partnerships that break China’s stranglehold on mineral supplies.

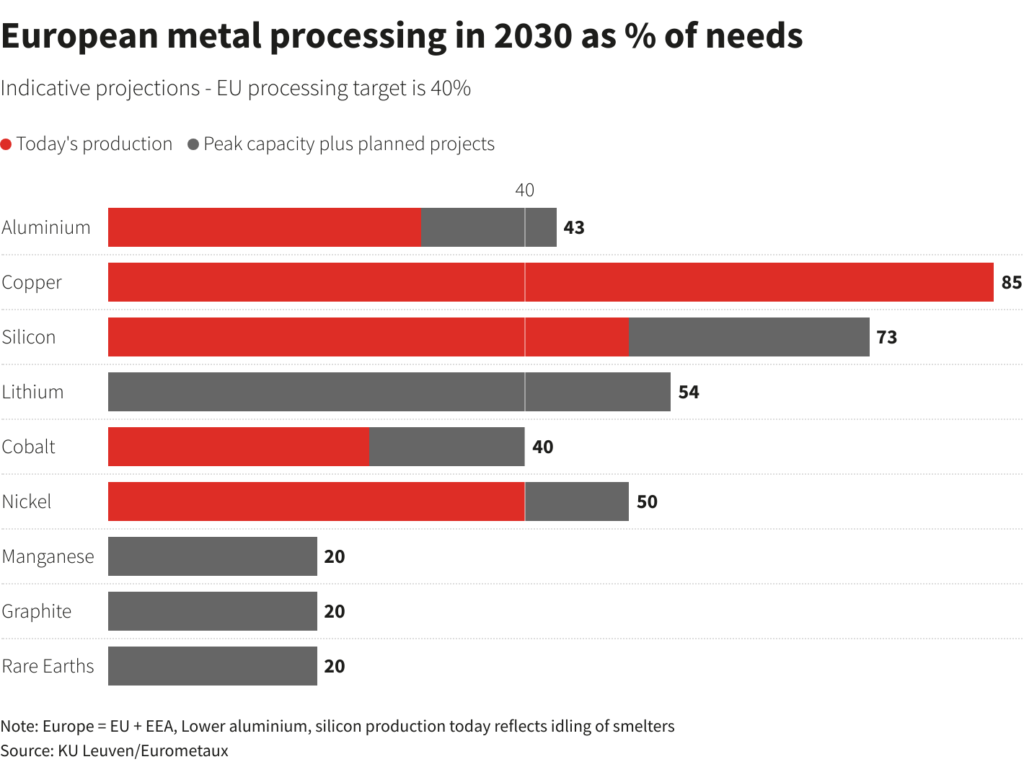

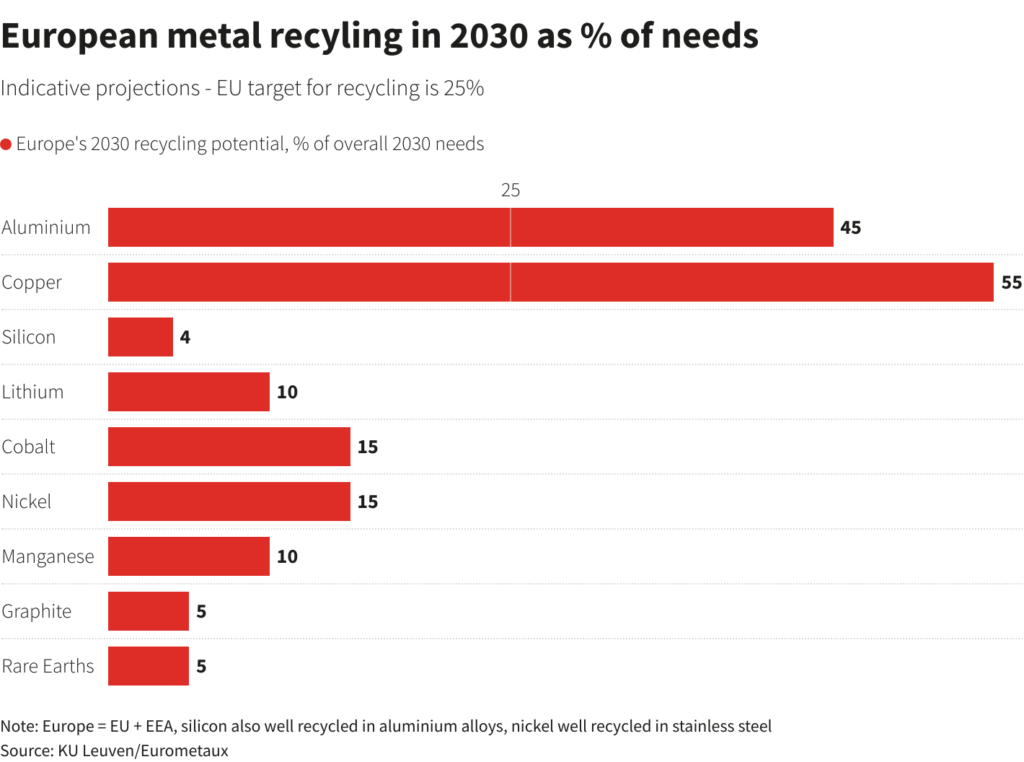

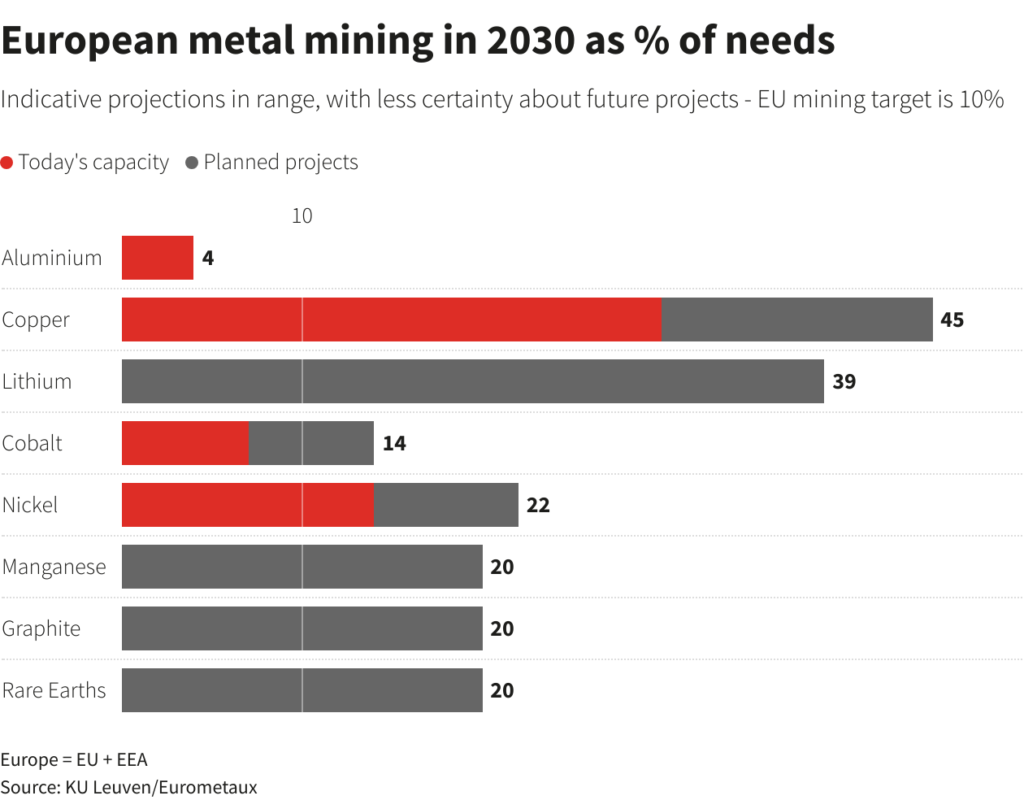

The Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), due to enter force in early 2024, says the bloc should mine 10%, recycle 25% and process 40% of its annual needs of 17 key raw materials by 2030.

The materials are essential for vehicle batteries, wind turbine magnets and other clean tech products the EU wants to manufacture. The CRMA aims to reduce the bloc’s reliance on China, which dominates global mineral processing and has already threatened EU supply with export curbs.

Studies forecast recycling will be limited until 2035-2040, when metals re-enter the market as scrap.

Researchers from Belgian university KU Leuven concluded in a 2022 report that the period to 2030 will be the most challenging for metal supply, highlighting risks for copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt and rare earth elements.

The CRMA aims to speed up granting of project permits, which for a mine should be within 27 months, from a potential 10-15 years now, but other obstacles remain.

Eurometaux, Europe’s association for non-ferrous metals, says Europe has potential, but needs cheaper energy and EU financing, pointing to funds on offer in the United States, Canada or Japan.

The European Union has loosened state aid rules and plans to spend 3 billion euros ($3.3 billion) to boost battery production, but the sums are dwarfed by the $369 billion of green subsidies in the US Inflation Reduction Act. A European Sovereignty Fund has been mooted, but since dropped.

Industry groups say prioritization of US over EU projects by the likes of Nyrstar in gallium and germanium recovery and Jervois Cobalt in mining and refining highlights the gap.

Meanwhile, higher EU higher energy costs have forced widespread idling of electricity-intensive metal smelters – EU aluminum production fell 35% in 2022 and has dropped further this year.

EU has plans to reform its electricity market, but this will take time to guarantee affordable renewable energy.

In mining, repurposing some existing sites might yield critical raw materials that were considered to be waste, according to Lawrence Dechambenoit, global head of external affairs at Rio Tinto, the world’s second-largest mining company.

But for lithium, he said, Europe urgently needed new mines.

Eurometaux says identified projects could meet almost 40% of EU supply by 2030, but a number are uncertain.

These include Portugal, which has delayed auctioning of mining licences for battery-grade lithium and is now mired in a corruption scandal and Serbia, which revoked licences in 2022 for Rio Tinto’s $2.4 billion lithium project.

Nicola Beer, the German liberal who steered the CRMA through the European Parliament, is more confident on the three targets.

“I get calls from countries asking what they can do, which I take as a positive sign,” she said.

However, she also points to what she calls the “fourth leg of the chair” – innovation to minimise material use or find substitutes. As an example, she passes round a black disc made from wood that can serve as graphite in batteries.

One effective move would be a shift to more modest electric vehicles with smaller batteries. Julia Poliscanova, a senior director at campaign group Transport & Environment, says this could cut lithium and nickel demand by a quarter.

Niclas Poitiers, research fellow at Bruegel think-tank in Brussels, says Europe’s ultimate aim of being a clean tech leader may be better served sourcing minerals from reliable allies and concentrating on higher-end products such as batteries, rather than ‘on-shoring’ mineral production.

“The base of our wealth is that we focus in manufacturing the most value-added parts and we outsource the things that are not high value-added. And this is something that is very difficult to change,” he said.

The CRMA does stress a need to diversify imports.

The European Union has indeed signed multiple partnerships from Argentina to Zambia and hopes its 300 billion euro Global Gateway infrastructure investment scheme will entice resource-rich countries keen to diversify their economies and also reduce their own dependence on China.

“It’s a win-win proposition,” Poitiers said.