Doctor Copper has sat serene amid the chaos engulfing London Metal Exchange (LME) trading this month.

The London copper market was briefly shaken by the margin meltdown that triggered the March 8 suspension of the LME nickel market with a short-lived spike up to a new all-time high of $10,845 per tonne.

But since then LME three-month copper has done little more than tread water, last trading at $10,340 per tonne.

This is in part because the London copper contract was already subdued after its own bout of unruliness in October last year, when the LME intervened to limit acute time-spread tightness.

It is also because copper seems much less exposed to a disruption of Russian supply than other industrial metals such as nickel which has been rocked to the point of breakdown by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But is it? Or is Doctor Copper in for an unwelcome surprise?

Sanguine about supply?

Russia is a big copper producer with refined production of around one million tonnes per year, representing about 4% of global production.

It is also a big exporter of both unwrought metal and copper wire but doesn’t have the same commanding position in Western supply chains as, say, in palladium, where Norilsk Nickel alone accounts for 45% of global production.

Moreover, much of what is exported ends up in China, which absorbs around 400,000 tonnes per year of Russian copper.

The assumption is that the rest of the world can live without Russian copper and that China will simply soak up what is displaced from Western markets.

It’s probably one reason why the LME’s Copper Committee, representing a broad spectrum of consumers, producers and merchants, felt able to vote for a ban on new deliveries of Russian copper to the exchange.

However, the LME executive has made it clear that it’s not in the business of pre-empting governments on imposing sanctions and has no plans to ban unilaterally any Russian metal.

Maybe it’s just as well, since not everyone is so sanguine about the consequences of what the Russian government terms its “special operation” in Ukraine.

Goldman Sachs argues that copper is “mispricing Russian supply risk”, the super-cycle bull keeping its elevated target of $12,000 per tonne over a 12-month time-frame. (“Copper Convergence Rally Begins”, March 3, 2022)

Russian exports – mind the gap

Russian copper export flows are more nuanced than they appear at first sight and last year’s figures are a poor starting point for analysis.

The country’s exports of unwrought refined copper totalled 463,000 tonnes in 2021, the lowest annual outflow since 2014, according to the International Trade Commission (ITC).

That reflected significantly lower output at Norilsk Nickel due to mine flooding and trade disruption resulting from a temporary 15% export tax between August and December.

It’s worth noting that January’s exports were a whopping 117,000 tonnes, compared with 35,500 tonnes in January 2021, which attests to the bulge effect in outbound flows around the tax hit.

Exports averaged around 700,000 tonnes in the 2018-2020 period, supplemented by 150,000 tonnes of copper wire, which is a better historical yardstick than last year’s low-ball count.

However, last year’s trade figures highlight a significant kink in the flow of Russian copper to China.

Russia counted 155,000 tonnes going out to China but China counted 403,000 tonnes of Russian metal coming in.

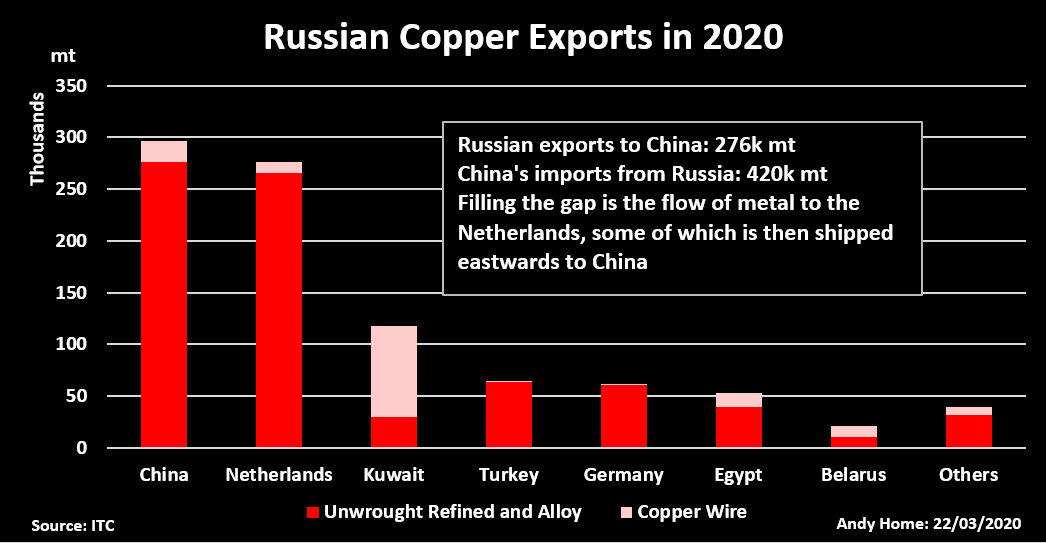

There was a similar gap in the 2020 trade figures, Russia exporting 276,000 tonnes to China and China importing 420,000 tonnes of Russian copper.

It’s clear that a significant amount of Russian copper being shipped to the Netherlands – the second largest destination after China – is being churned through either physical or LME trading systems before heading on a boat to Shanghai.

Although there is a direct rail link between Russia and China, currently used to transport copper concentrates, it has little spare capacity for refined metal, according to Goldman Sachs.

The majority of the country’s refined copper exports to China flow through the Black Sea or via European ports such as Rotterdam.

Both shipping routes are becoming increasingly problematic as self-sanctioning by logistics companies disrupts Russia’s sea-borne trade.

“Until the shipping constraints subside, these copper units are likely to be dislocated from the market,” according to Goldman, which adds that “this implies up to a 50-60kt per month reduction of copper supply to the ex-Russia refined market.”

Thin buffer

It’s questionable to what extent the global refined copper supply chain can handle that scale of disruption right now.

Global exchange stocks are low. There are currently 276,000 tonnes of copper sitting in LME, Shanghai Futures Exchange and CME warehouses.

Total inventory has risen by 85,800 tonnes so far this year but that’s down to the seasonal stock build in China around the lunar new year holidays. Compared with this time last year exchange inventory cover is down by 121,000 tonnes.

LME stocks have fallen by almost 9,000 tonnes since the start of the year and at 79,975 tonnes are equivalent to just over a day’s global usage.

Time-spreads are relaxed but that may have as much to do with the LME’s backwardation caps across all its main contracts as it has with copper’s own dynamics.

By any historical gauge LME inventory is close to depleted and highly vulnerable to any renewed panic buying such as seen in the run-up to last October’s squeeze.

Russian copper isn’t yet sanctioned and it won’t be banned by the LME, for now at least. And even if it were, there’s no doubt that it would find a ready home in China.

Eventually.

But getting it to China means transhipping it through Europe and that’s getting harder by the day.

A readjustment of Russian copper trade flows may not be nearly as smooth as Doctor Copper seems to be expecting.