In the past two years, cobalt prices have more than tripled from roughly $25,000 per metric ton to more than $79,0001 in response to supply constraints anticipated as electric vehicles (EVs) continue to gain traction. In 2017, the Congo accounted for 58% of global cobalt production, explaining the fear that geopolitical instability will cause shortages. In ARK’s view, however, the combination of higher prices and new battery chemistries will encourage mining in other countries while battery manufacturers lower their exposure to cobalt.

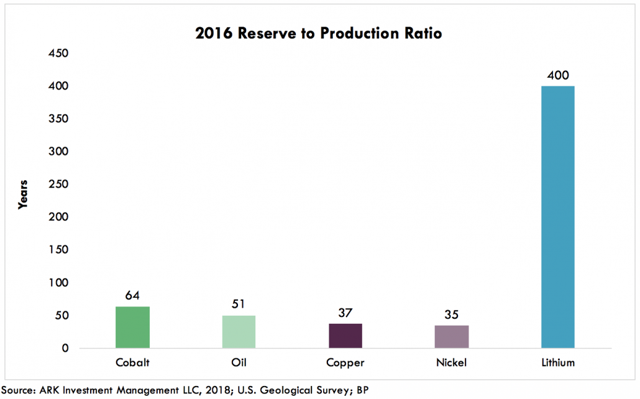

Since 2001, cobalt production has tripled from nearly 37,000 to 110,000 metric tons while reserves have remained fairly flat at roughly 7,000,000 metric tons.2 At today’s production levels, cobalt reserves should last for 64 years, longer than most commodities with the exception of lithium, as shown below. Given the recent price spike, the exploration for cobalt should increase meaningfully, adding to its reserve life for the first time in nearly 20 years.

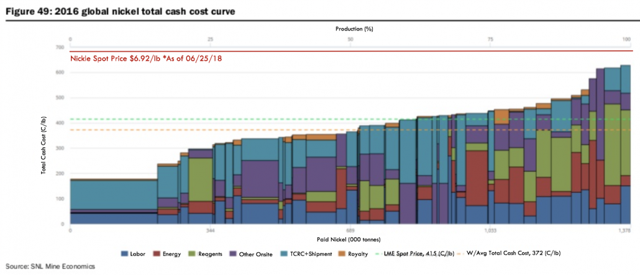

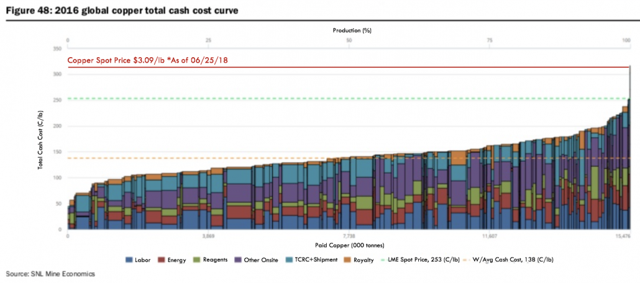

Unlike lithium, cobalt is a by-product of the mining for nickel and copper. As a result, its production and reserves are tied more to the price of those primary metals than that of cobalt. Since 2016, spot prices of both nickel and copper have increased significantly, as shown below, which should stimulate investment in new mines and projects.

Even if the prices and production of copper and nickel were to disappoint during the next few years, newer batteries are becoming less dependent on cobalt. As shown below, new chemistries could reduce the cobalt content in a 50 kWh car by roughly 75%, from 19.9kg to less than 4.5kg. For context, GM designed the original Chevy Bolt with nickel manganese cobalt (NMC 111) batteries, the cobalt content of which is nearly three times that in Tesla’s (NASDAQ:TSLA) Model 3 nickel cobalt aluminum (NCA) batteries. NMC 622 and NMC 811, which are on their way to being commercialized at scale, also require less cobalt.