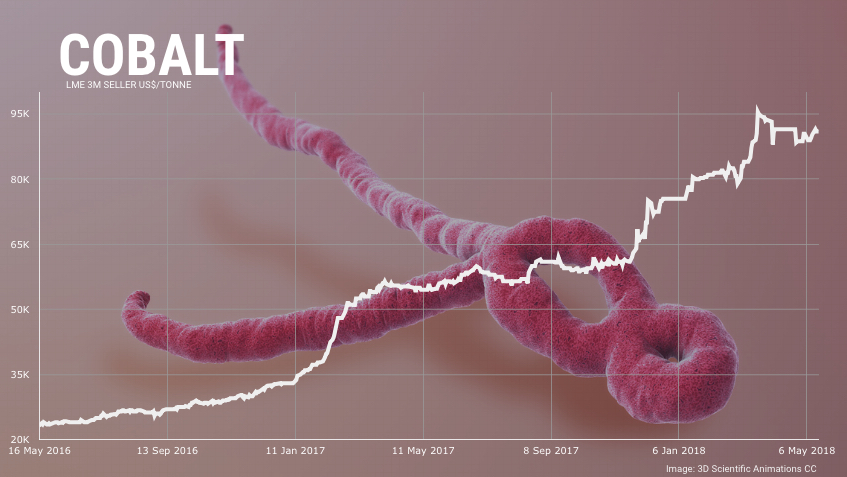

The price of cobalt has been drifting after hitting near 10-year peaks in March to exchange hands for $91,000 a tonne on Friday.

Cobalt is still up nearly fourfold since hitting multi-year lows at the beginning of 2016 as worries about supply of the metal, a crucial element in batteries, combine with expectations of booming demand from the electric vehicle sector.

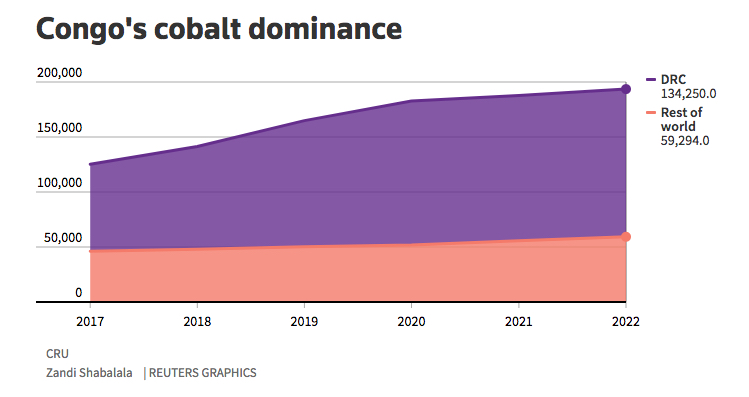

Supply risks for cobalt are centred on the Democratic Republic of the Congo which is responsible for nearly two-thirds of world output. And the country’s share will only increase over the next five years (see chart).

Fears of disruption from the conflict ridden central African country has intensified after an outbreak of the deadly ebola disease and the possibility of a return to civil war in the run up to long-postponed national election now set for December.

On Friday, the world health organization raised the the DRC’s ebola health assessment risk to “very high.”

“The risk of international spread is particularly high since the city of Mbandaka [population 1.2m] is in proximity to the Congo river, which has significant regional traffic across porous borders,” the WHO said in a statement noted.

On Sunday, the DRC recorded its 26th death in the northwest Equateur province. The disease is named after the Ebola river in the country.

Glencore quandary

Troubles are also mounting for top cobalt producer Glencore.

The Swiss commodities giant is in a bitter fight with its former partner in the DRC, Dan Gertler, who is seeking up to $3 billion in unpaid and future royalties.

The Israeli businessman, under sanctions from the US Treasury dept over allegations of bribery, is a close confidant of DRC president Joseph Kabila, in power since 2001.

It was also reported on Friday that Britain’s Serious Fraud Office is planning to open a formal bribery investigation into the company’s dealing with Gertler.

In turn, state-owned Gecamines which is a shareholder in Glencore’s Katanga operations in the country, is accusing the company of “draining” money from the joint venture. Gecamines, which has powerful political backing, has threatened unspecified action to ensure a greater share of profits from the venture.

With some of the frothiness gone from the spot market, a new report argues that anything below $100,000 per tonne is a buy.

Citi, a US investment bank, says prices for the raw material (now mainly produced in chemical compounds) are set to rise by a further 20% over the next two years hitting $100,000 a tonne by the fourth quarter this year, and average $110,000 by 2020.

Citi calculates that Katanga together with Glencore’s Mutanda mine in the DRC are expected to contribute 35,500t or 27% of global supply during 2018. Those figures are set to rise to 59,300t and 39% next year.

The bank believes any disruption from these mines would see cobalt hit six figures sooner than than expected.

The China-Congo-Cobalt nexus

The DRC today has six of the top 10 cobalt mines globally.

By 2022, due primarily to Chinese investment starting with the 2017 takeover of US-based Freeport McMoRan’s Tenke Fungurume mine by China Moly, the DRC will host the nine largest cobalt producers.

Congo also holds half the world’s reserves of cobalt which is almost always mined as a by-product of copper and nickel.

Not only is primary production highly concentrated, but the downstream industry is beginning to resemble a monopsony.

China, despite having no cobalt resources of its own, is responsible for 80% of the world’s cobalt chemical production, which overtook metal production around four years ago.

Beijing has made electric vehicles a centrepiece of its war on pollution. It also wants the sector to spearhead the country’s Made in China 2025 innovation drive.

The China-Congo-Cobalt-nexus poses particular problems for tech companies like Apple and automakers in the US and Europe which has been scrambling to secure supply.

Not only in terms of securing supply but also the growing consumer awareness of ethical sourcing of materials. This could lead to premium pricing for cobalt produced outside Congo. Chinese processors have admitted that they cannot say unequivocally that some of the cobalt in the supply chain is not from child or forced labour.

Glencore CEO Ivan Glasenberg, told a conference in Lausanne in March that the auto industry is “waking up too late” to the fact that China will hold most of the world’s supply of cobalt:

“If cobalt falls into the hands of the Chinese, yeah you won’t see EVs being produced in Europe etc. They are waking up too late … I think it’s because the car industry has never had a supply chain problem before.”