If it’s grown, drilled or dug up, chances are there’s not enough of it in China.![]()

Beijing’s ability to manage the mismatch between its scarce natural resources and vast industrial output is now playing out in the market for lithium, a mineral crucial to the world’s transition away from fossil fuels. It’s an effort complicated by skyrocketing prices, geopolitical tensions and the environmental devastation that can be wrought by a pell-mell approach to extraction.

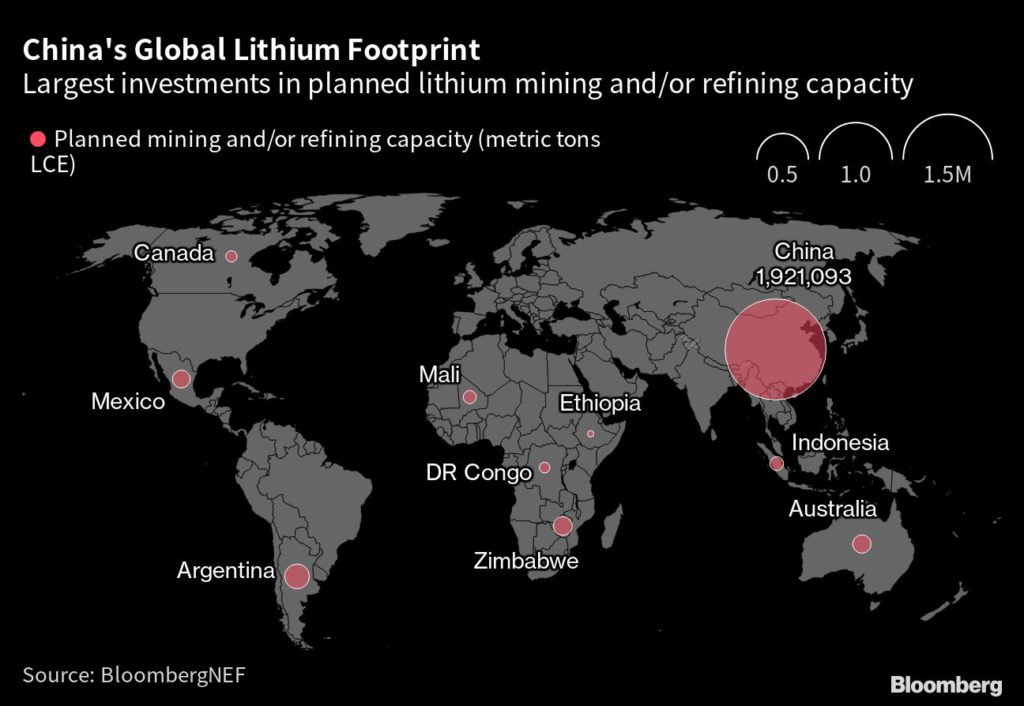

China is the world’s biggest producer of new energy vehicles but holds only a modest slice of global reserves of lithium, used in the batteries that power electric cars. In that regard, lithium is of apiece with many of the commodities foundational to a modern economy — think crude oil for fuel, iron ore to make steel, or soybeans to feed pigs — where China is overly reliant on foreign supplies for its often world-beating production.

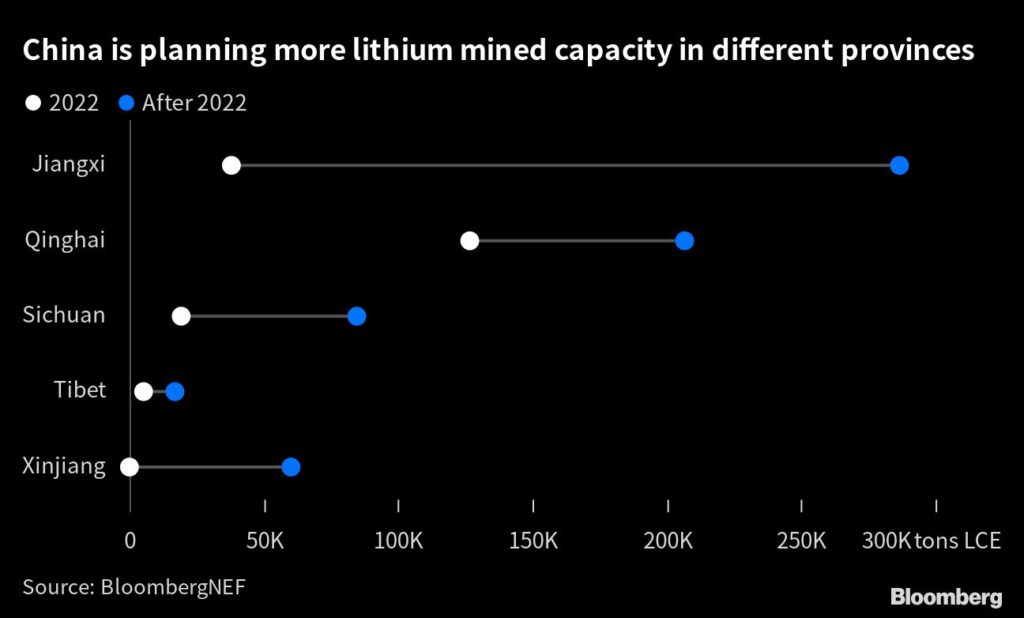

A government inspection last month, which has shuttered some producers at a lithium mining hub in eastern China, is a clear signal that Beijing is turning its attention to better marshaling its domestic resources of the mineral, against a backdrop of record prices and short supply across the globe.

Lithium producers in Jiangxi province’s Yichun city were targeted for environmental infringements and unlicensed mining, according to local media, threatening around a tenth of global output. Of particular concern was the extraction of lepidolite, a lithium-bearing rock often overlooked as lower-quality. The crackdown could signal that even lepidolite is now emerging as a key resource that officials are keen to preserve.

“Due to the mammoth growth of lithium prices over the past two years, there has been an increased interest in capturing and exploring lithium resources within domestic shores,” said Leah Chen, an analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

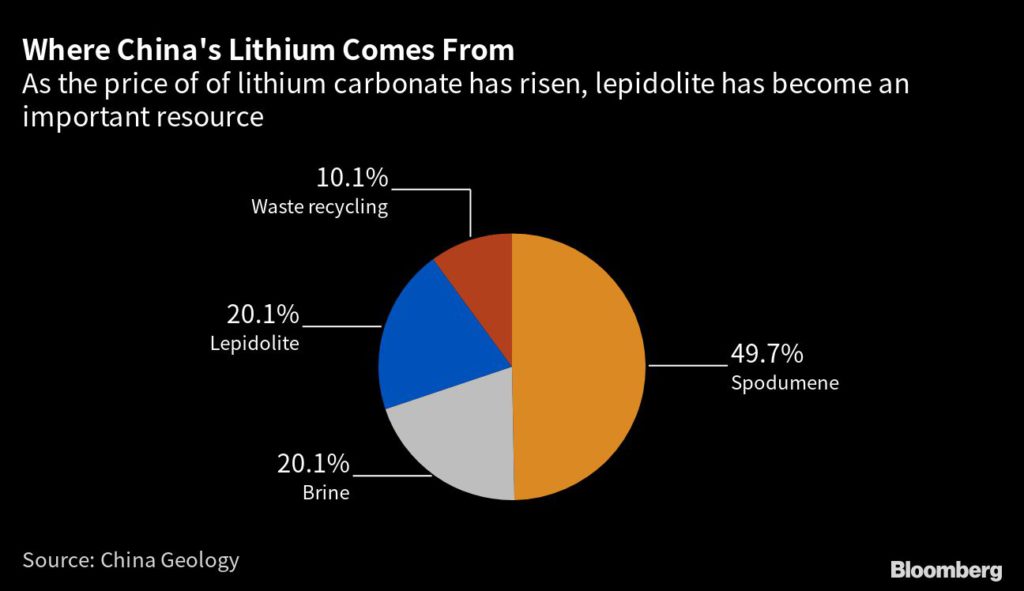

Like many other metals, China is central to the supply chain, housing over half of the world’s refining capacity but relying on imports for about two-thirds of the raw material. According to the US Geological Survey, it accounts for 8% of the world’s reserves, which are mostly held in an igneous rock called spodumene. Saltwater lakes are another key source.

Lithium prices hit an all-time high last year as booming demand for electric vehicles outstripped production. Despite a drop of over 40% from its November peak, lithium carbonate, a refined version of the metal, is still eight times more expensive in China than it was in 2020.

It’s the kind of circumstance that often tempts miners to skirt regulations in the pursuit of big rewards. That can deplete reserves too quickly, put the environment at risk and could ultimately rebound on buyers in the autos industry if they run afoul of increasingly stringent ESG rules adopted by investors.

Dirty mining

Some Chinese companies had already been pulled up by the government for infringements, including incidents of pollution, before the February inspection of Yichun. Another issue is so-called high-grading, where miners extract the best material first without worrying about how to conserve a deposit.

“High-grading is always a concern in these unregulated, marginal mines that will unfortunately lead to more rapid exhaustion of the reserve,” said Martin Jackson, head of Battery Raw Materials at CRU Group.

For lepidolite, which accounted for about a fifth of China’s lithium output in 2021, according to the China Geology journal, there are additional costs arising from its low-yield that directly conflict with lithium’s climate-friendly credentials. Yichun’s lepidolite rocks contain less than 1% lithium, according to the journal, which typically makes extraction more energy-intensive and expensive.

Lepidolite is “is a little bit opaque to most of us, but what we see, generally speaking, is very high-cost production,” Paul Graves, the chief executive officer of US producer Livent Corp., told a BMO Capital Markets conference in February.

“I don’t like the word dirty,” he said. “I just can’t think of a better one. A difficult process to do in an environmentally friendly way.”

For every ton of lithium carbonate equivalent processed from lepidolite, 200 tons of waste is produced, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. All that needs treating and disposing of, said Tom Drabble, an ESG analyst at the consultancy.

“Some companies opt to sell the waste, but others have started to collect waste in large tailings ponds,” he said. “Tailings ponds have associated risks, if not managed correctly, of adversely affecting local communities through water pollution via leaching and taking up large areas of land.”

Some of China’s biggest names in batteries, including Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. and Gotion High-Tech Co., have invested in lepidolite mining to lock in supplies. That poses the question of whether they’ll eventually be penalized by investors for using raw materials with a big carbon footprint.

The checks have no impact on CATL and its project in Yichun is progressing as planned, the company told investors in a call on Thursday, according to a filing. CATL operates in strict accordance with local laws and regulations, it said. Gotion didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

While it’s too soon to assess the downstream impact, Chinese output that relies on domestic lithium production “is inferior to overseas-sourced, China-processed lithium in several key ESG areas,” Dennis Ip and Leo Ho, analysts at Daiwa Capital Markets, said in an emailed response to questions.

China’s lithium resources are mainly concentrated in Jiangxi, Qinghai, Sichuan and Tibet. It’s started looking in Xinjiang, too, a region that’s drawn scrutiny from US lawmakers amid allegations of forced labor that Beijing has denied. Chinese miners, automakers and battery manufacturers have snapped up resources further afield, from Argentina to Zimbabwe, increasing competition globally for a key resource.

“How to best utilize China’s reserves and how to be more self-sufficient have become more and more important, especially now there’s more geological tension, like between China and the US,” said Matty Zhao, head of Asia-Pacific research on basic materials at Bank of America Corp.