Achieving photovoltaic power generation for over 1,000 continuous hours, efficiency more than 20%

News and Information

October 8, 2022 By Editor

October 7, 2022 By Editor

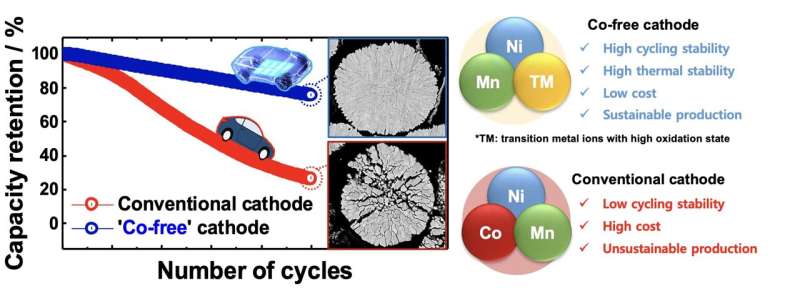

Li-ion batteries, rechargeable batteries based on lithium ions, are currently used to power a wide range of electronic devices, ranging from smartphones to portable computers, toys, wireless headphones, and electric vehicles. Despite their remarkable performances, these batteries are made using some unsustainable and expensive raw materials.

The most notable among these materials is cobalt (Co), which is used to create layered cathodes for Li-ion batteries. Because of the recent surge in demand for electric vehicles, cobalt is rapidly becoming scarce on Earth, also due to the rising demand from the technology and electronics industry.

Researchers at Hanyang University and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory have recently shown that creating highly performing layered cathodes without using Co could in fact be possible. Their paper, published in Nature Energy, could ultimately contribute to the development of more sustainable and affordable Li-ion battery solutions.

“Prof. Sun and I have been working together on cathode materials for the past 20 years,” Prof. Chong S. Yoon, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told TechXplore. “With the increasing depletion of Co and its supply uncertainty, we recognized that it is becoming increasingly imperative to eliminate Co from Ni-rich layered cathodes (NCA or NCM) used in electric vehicles.”

So far, eliminating Co from layered cathodes for Li-ion batteries has proved extremely challenging. This is because even a small amount of this material can significantly improve the structural stability of cathodes, which in turn expedites the so-called Li-intercalation kinetics. This is an essential chemical process that ultimately enables high performances in batteries. To overcome this limitation, some researchers have been exploring the potential of a cathode made of Li(NixMn1-x)O2; arguably the most straightforward cathode-free composition.

“Li(Ni0.5Mn0.5)O2 is a well-studied Co-free cathode with stable cycling stability, but it provides insufficient capacity for today’s EVs,” Yoon said. “There have been attempts to increase the Ni content in Li(Ni0.5Mn0.5)O2 to increase its capacity, but the capacity problem remained unresolved. Without Co, it is difficult to extract Li from the host structure.”

To overcome the challenges encountered during previous attempts at creating highly performing Li(Ni0.5Mn0.5)O2 cathodes, Yoon and his colleagues increased their cathodes’ operating voltage from 4.3 V to 4.4 V. This allowed them to extract a larger fraction of Li from Li(Ni0.9Mn0.1)O2 , which simultaneously increased the energy density and power density at the batteries’ highest operating voltage. To ensure that their Li-ion battery remained stable at 4.4V (the highest operating voltage), the team then had to re-engineer the batteries’ cathode microstructure and electrolyte.

“From our experience, we knew that introducing dopants with high oxidation states (Mo, W, Sb, Ta, etc.) refines the primary particle size and stabilizes the delithiated host structure,” Yoon said. “We took a heuristic approach based on our past experience to determine that doping the Li(Ni0.9Mn0.1)O2 cathode with 1 mol% Mo gives the best performance. Fluoroethylene carbonate was also added to the conventional electrolyte to support the electrolyte at 4.4 V and protect the cathode surface from electrolyte attack. 1 mol% Mo—Li(Ni0.9Mn0.1)O2 cycled 1,000 times while retaining 86% of the initial capacity which is more than sufficient to meet the battery life specified by the electric vehicle manufacturer.”

The main difficulty that Yoon and his colleagues encountered when trying to operate their 1 mol% Mo—Li(Ni0.9Mn0.1)O2 cathode at 4.4 V was capacity fading during prolonged cycling (i.e., a loss of capacity over time that plagues all rechargeable batteries based on Ni-rich layered cathodes). To ensure that their battery had enough life to power devices for a reasonable amount of time, they first had to resolve this capacity fading issue.

“The exceptional cycling stability of 1 mol% Mo—Li(Ni0.9Mn0.1)O2 at 4.4 V is largely owed to the grain size refinement and cation ordering,” Yoon explained. “Mo6+ ions tend to segregate along interparticle boundaries and inhibit grain growth during high-temperature heat treatment which is necessary to convert the hydroxide precursor to Li(Ni0.9Mn0.1)O2. Grain boundaries in this ultrafine-structured cathode increase fracture toughness by deflecting cracks generated by the abrupt lattice contraction near the charge end.”

The grain boundaries in the researchers’ cathode can also act as fast diffusion paths for Li+, which remove local inhomogeneities due to their composition and suppress intragranular fractures. By introducing Mo6+, the team was able to arrange cations in their cathode in a specific way (i.e., intermixing Li and Ni ions). This unique design stabilizes the cathode’s structure when it is most vulnerable due to the non-uniform extraction of Li+ ions.

“Our findings suggest that developing a high-performance Co-free layered cathode is no-longer an elusive goal,” Yoon said. “The proposed 1 mol% Mo—Li(Ni0.9Mn0.1)O2cathode cycling at a high voltage is an economically viable solution that is achievable with current manufacturing technology. In addition, by clarifying the intrinsic role of Co during the extraction of Li+ from the host structure, this work offers a material design criterion for selecting a tertiary doping element for ensuring the structural and mechanical durability of Co-free layered cathodes.”

The cathode design and composition proposed by Yoon and his colleagues could guide future research efforts aimed at improving the general performance of Ni-rich layered cathodes. In addition, their work might pave the way towards the creation of highly performing Co-free battery technologies, which could be more sustainable and affordable that their Co-based counterparts.

“For high-performance EVs with a long driving range and improved safety, the next generation Li-ion batteries will likely be all-solid-state batteries (ASSB) featuring Ni-rich Co-free cathodes,” Yoon added. “We are now investigating the possibility of applying the proposed Co-free cathode to ASSB.”

October 6, 2022 By Editor

Bristol-led team uses nanomaterials made from seaweed to create a strong battery separator, paving the way for greener and more efficient energy storage.

Sodium-metal batteries (SMBs) are one of the most promising high-energy and low-cost energy storage systems for the next-generation of large-scale applications. However, one of the major impediments to the development of SMBs is uncontrolled dendrite growth, which penetrate the battery’s separator and result in short-circuiting.

Building on previous work at the University of Bristol and in collaboration with Imperial College and University College London, the team has succeeded in making a separator from cellulose nanomaterials derived from brown seaweed.

The research, published in Advanced Materials, describes how fibres containing these seaweed-derived nanomaterials not only stop crystals from the sodium electrodes penetrating the separator, they also improve the performance of the batteries.

“The aim of a separator is to separate the functioning parts of a battery (the plus and the minus ends) and allow free transport of the charge. We have shown that seaweed-based materials can make the separator very strong and prevent it being punctured by metal structures made from sodium. It also allows for greater storage capacity and efficiency, increasing the lifetime of the batteries — something which is key to powering devices such as mobile phones for much longer,” said Jing Wang, first author and PhD student in the Bristol Composites Institute (BCI). Dr Amaka Onyianta, also from the BCI, who created the cellulose nanomaterials, co-authored the research.

“I was delighted to see that these nanomaterials are able to strengthen the separator materials and enhance our capability to move towards sodium-based batteries. This means we wouldn’t have to rely on scarce materials such as lithium, which is often mined unethically and uses a great deal of natural resources, such as water, to extract it.

“This work really demonstrates that greener forms of energy storage are possible, without being destructive to the environment in their production,” said Professor Steve Eichhorn who led the research at the Bristol Composites Institute.

The next challenge is to upscale production of these materials and to supplant current lithium-based technology.

October 5, 2022 By Editor

Electric cars offer several benefits over tried-and-true gas vehicles, from quiet and emissions-free operation to instant torque on demand. That said, EVs aren’t perfect, and there are challenges to be aware of before you head out and buy your first model.

Electric vehicles use large batteries to store electricity needed to power the motor(s). When those batteries’ power is depleted, EV owners must stop to recharge before hitting the road again. Over time, all that charging and use can wear down a battery’s ability to maintain capacity and capability. Different batteries wear at different rates, and driving habits have a big impact on longevity as well. Let’s take a closer look at battery degradation and its causes.

Electric car batteries are just like the battery pack in cell phones or notebook computers in that they start to degrade over time and with use. Repeat discharge and charge, as well as thermal wear, can eventually reduce energy capacity and efficiency to a point that the battery is no longer able to provide decent range and charging performance. Most new EV models have special car battery technology and programming to prevent the battery from being completely discharged, which can help extend battery life and help the batteries maintain charging performance.

Depending on the car, operating in extreme temperatures can mimic true battery degradation. Hot and cold temperatures have similar effects on EV battery capacities by reducing range and slowing charging speeds. Beyond the obvious impact that temperatures have on the batteries themselves, the use of climate control systems and other electrical components can rapidly deplete battery power.

What can you do to keep your EV battery chugging along as expected? Several things, as it turns out:

Every electric car sold in the United States leaves the dealer’s lot with a battery warranty that extends to at least eight years or 100,000 miles. Some go above and beyond those numbers, but you can rest easy for at least eight years if you purchase a new EV. That’s not to say that your battery will last that long, however, so it’s not a guarantee that you’ll have eight years of trouble-free operation. Some manufacturers’ warranties carry stipulations on battery condition or operation before coverage is provided, so it’s important to understand your car’s warranty.

None of that tells us battery lifespan, however. In most cases, battery degradation happens slowly, with as little as a few percentage points of capacity every several years. Cars that operate primarily in extremely hot or cold conditions may see that decline happen much more quickly, but few people live at the far ends of the temperature spectrum without at least short periods of intermediate temperatures for relief. In most cases, electric car battery life expectancy should hit at least 100,000 miles before showing noticeable signs of degradation, and should carry on to 200,000 or more if properly maintained. The bottom line is that lithium-ion batteries are becoming more advanced and durable as time goes on, so battery longevity should not be a concern for the average EV user.

It’s true that gas vehicles are usually less expensive and easier to refuel, but there are several benefits to owning an EV that have nothing to do with costs. One of the biggest pros of owning an electric car is the reduced need for regular maintenance. There are no oil changes, no mechanical components to break underhood, no exhaust system, and the life of other components such as brakes can be extended. Many people report that driving an electric car is more relaxing than a gas vehicle, because of the lack of engine noise.

Many electric models offer significant performance benefits over gas vehicles as well. This applies not only to intended high-performance cars from Porsche, Tesla, and others, but even to everyday commuter vehicles. The immediate torque and acceleration can make electric cars exhilarating to drive, and make them quicker than most people expect, depending on driving habits. Plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEV) offer some of these benefits over a traditional gasoline vehicle, but they also must rely on fuel to provide power when the electricity runs out.

There may also be tax credits available, depending on the electric car you opt for. The United States government offers a one-time tax credit of up to $7,500 to buyers of eligible electric cars—and various states offer tax credits on select models, too—which lowers the effective cost of the purchase.

All of that, and we haven’t even mentioned the complete reduction of CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions in everyday driving and the fact that gas prices fluctuate wildly. Fuel costs are a big motivator for many buyers.

There are a few downsides (battery basics) to owning an electric car that might not be immediately apparent when you are standing on the dealer’s lot trying to make a car purchase. Depending on your location, you may or may not have ready access to charging stations. This is especially true for people who live in apartment buildings or those who rent, as it can be impossible to install a home charging system.

You may also find that electric cars take too long to charge, even if there is a charging station nearby. Unlike filling up a gas tank, which can take a few minutes, most electric vehicles take much longer to recover a sizable portion of their range. This can make road trips impractical for many, as the requirement to stop and charge for half an hour or more can turn a simple trip into a long, painful one.

Last, there is the issue of purchase cost. Electric cars, no matter the type, size, or technology, are usually more expensive than comparable gas vehicles.

October 4, 2022 By Editor

October 3, 2022 By Editor

Researchers at the Dept. of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the University of Tennessee-Knoxville discovered a key material needed for fast-charging lithium-ion batteries. The commercially relevant approach opens a potential pathway to improve charging speeds for electric vehicles.

Lithium-ion batteries, or LIBs, play an essential role in the nation’s portfolio of clean energy technologies. Most hybrid electric and all-electric vehicles use LIBs. These rechargeable batteries offer advantages in reliability and efficiency because they can store more energy, charge faster,, and last longer than traditional lead-acid batteries. However, the technology is still developing, and fundamental advances are needed to meet priorities to improve the cost, range and charge time of electric-vehicle batteries.

“Overcoming these challenges will require advances in materials that are more efficient, and synthesis methods that are scalable to industry,” says ORNL Corporate Fellow and corresponding author Sheng Dai.

Results published in Advanced Energy Materials demonstrate a novel, fast-charging battery anode material achieved by using a scalable synthesis method. The team discovered a novel compound of molybdenum-tungsten-niobate, or MWNO, with fast rechargeability and high efficiency that could potentially replace graphite in commercial batteries.

For decades, graphite has been the best material used to make LIB anodes. In basic battery design, two solid electrodes—a positive cathode and a negative anode—are connected by an electrolyte solution and a separator. In LIBs, lithium ions move back and forth between the cathode and anode to store and release energy that powers devices. One challenge for graphite anodes is that the electrolyte decomposes and forms a buildup on the anode surface during the charging process. This buildup slows the movement of lithium ions and can limit battery stability and performance.

“Because of this sluggish lithium-ion movement, graphite anodes are seen as a roadblock to extreme fast charging,” says ORNL postdoctoral researcher and first author Runming Tao. “We’re looking for new, low-cost materials that can outperform graphite,”

The DOE’s extreme fast-charging goal for electric vehicles is set at 15 minutes or less to compete with refuel times on gas-powered vehicles, a milestone that has not been met with graphite.

“Our approach focuses on nongraphite materials, but these also have limitations,” says Tao. “Some of the most promising materials—niobium-based oxides—have complicated synthesis methods that are not well suited to industry.”

Conventional synthesis of niobium oxides such as MWNO is an energy-intensive process over open flame that also generates toxic waste. A practical alternative could push MWNO materials to become serious candidates for advanced batteries. Researchers turned to the well-established sol-gel process, known for safety and simplicity. Unlike conventional high-temperature synthesis, the sol-gel process is a low-temperature chemical method for converting a liquid solution into a solid, or gel, material and is commonly used to make glasses and ceramics.

The team transformed a mixture of ionic liquid and metal salts into a porous gel that was treated with heat to enhance the material’s final properties. The low-energy strategy also enables the ionic liquid solvent used as a template for MWNO to be recovered and recycled.

“This material operates at a higher voltage than graphite and is not prone to forming what is called a ‘passivation solid electrolyte layer’ that slows down the lithium-ion movement during charging,” says Tao. “Its exceptional capacity and fast-charging rate, combined with a scalable synthesis method, make it an attractive candidate for future battery materials.”

The key to the material’s success is a nanoporous structure that provides enhanced electrical conductivity. The result offers less resistance to the movement of lithium ions and electrons, enabling fast recharging.

“The study achieves a scalable synthesis method for a competitive MWNO material as well as providing fundamental insights on future design of electrode materials for a variety of energy storage devices,” says Dai.

The journal article is published as “Insight into the Fast-Rechargeability of a Novel Mo1.5W1.5Nb14O44 Anode Material for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries.”

The work was supported by the DOE Office of Science and used resources of the Spallation Neutron Source, a DOE Office of Science user facility at ORNL.