A Pohang University of Science & Technology research team succeeded in developing an anode-free lithium battery. The design maximized energy density and improved energy density by 40%.

The Pohang University of Science & Technology (POSTECH) research team led by Professor Soojin Park and PhD candidate Sungjin Cho (Department of Chemistry) in collaboration with Professor Dong-Hwa Seo and Dr. Dong Yeon Kim (School of Energy and Chemical Engineering) at Ulsan Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) have developed anode-free lithium batteries with performance of long battery life on a single charge.

The team’s study paper has been published in Advanced Functional Materials.

The number of newly registered electric vehicles (EVs) in Korea surpassed 100,000 units last year alone. Norway is the only other country to match such numbers. The core materials that determine the battery life and charging speed of now commonly seen EVs are anode materials. Korea’s domestic battery industry has been committed to finding revolutionary ways to increase the battery capacity by introducing new technologies or other anode materials. The team asked, “What if we get rid of anode materials altogether?”

The newly developed anode-free battery has a volumetric energy density of 977Wh/L which is 40% higher than the conventional batteries (700wh/L).

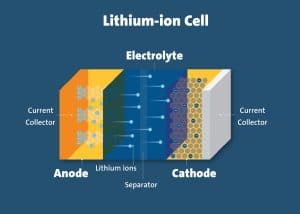

Batteries usually change the structure of anode materials as lithium ions flow to and from the electrode during repetitive charging and discharging. This is why the battery capacity decreases over time. It was thought that if it was possible to charge and discharge only with a bare anode current collector without anode materials, the energy density – which determines the battery capacity – would increase. However, this method had a critical weakness which causes significant swelling of the anode volume and reduces the battery lifecycle. It swelled because there was no stable storage for lithium in the anode.

To overcome this issue, the research team succeeded in developing an anode-free battery in a commonly-used carbonate-based liquid electrolyte by adding an ion conductive substrate. The substrate not only forms an anode protective layer but also helps minimize the bulk expansion of the anode.

The team’s study showed that the battery maintained high capacity of 4.2mAh cm-2 and high current density of 2.1 mA cm-2 for a long period in the carbonate-based liquid electrolyte. It was also proven both in theory and through experiments that substrates can store lithium.

Additionally, what’s drawing even more attention is that the team successfully demonstrated the solid- state half-cells by using Argyrodite-based sulfide-based solid electrolyte. It is anticipated that this battery will accelerate the commercialization of non-explosive batteries since it maintains high capacity for longer periods.

Once in a very long while the research news is just shocking. No Anode? Is it even a battery by definition? Well, yes, an anode of sorts forms up in the substrate.

As this concept is in its infancy there are lots of questions that will need answered. What comes to mind to those of use buying batteries is, how much lithium, the major cost in lithium batteries, is used for the same capacity as current technology?

That question determines the future of this technology. If a third less, this might be a revolution in battery construction.