Japan earmarks $107 billion for developing hydrogen energy to cut emissions, stabilize supplies

News and Information

June 8, 2023 By Editor

June 7, 2023 By Editor

When it comes to supplying energy for space exploration and settlements, commonly available solar cells made of silicon or gallium arsenide are still too heavy to be feasibly transported by rocket. To address this challenge, a wide variety of lightweight alternatives are being explored, including solar cells made of a thin layer of molybdenum selenide, which fall into the broader category of 2D transition metal dichalcogenide (2D TMDC) solar cells.

Published June 6 in the inaugural issue of the journal Device, researchers propose a device design that can take the efficiencies of 2D TMDC devices from 5%, as has already been demonstrated, to 12%.

“I think people are slowly coming to the realization that 2D TMDCs are excellent photovoltaic materials, though not for terrestrial applications, but for applications that are mobile—more flexible, like space-based applications,” says lead author and Device advisory board member Deep Jariwala of University of Pennsylvania. “The weight of 2D TMDC solar cells is 100 times less than silicon or gallium arsenide solar cells, so suddenly these cells become a very appealing technology.”

While 2D TMDC solar cells are not as efficient as silicon solar cells, they produce more electricity per weight, a property known as “specific power.” This is because a layer that is just 3 to 5 nanometers thick—or over a thousand times thinner than a human hair—absorbs an amount of sunlight comparable to commercially available solar cells. Their extreme thinness is what earns them the label of “2D”—they are considered “flat” because they are only a few atoms thick.

“High specific power is actually one of the greatest goals of any space-based light harvesting or energy harvesting technology,” says Jariwala. “This is not just important for satellites or space stations but also if you want real utility-scaled solar power in space.”

“The number of solar cells you would have to ship up is so large that no space vehicles currently can take those kinds of materials up there in an economically viable way. So, really the solution is that you double up on lighter weight cells, which give you much more specific power.”

The full potential of 2D TMDC solar cells has not yet been fully realized, so Jariwala and his team have sought to raise the efficiency of the cells even further. Typically, the performance of this type of solar cell is optimized through the fabrication of a series of test devices, but Jariwala’s team believes it is important to do so through modeling it computationally.

Additionally, the team thinks that to truly push the limits of efficiency, it is essential to properly account for one of the device’s defining—and challenging to model— features: excitons.

Excitons are produced when the solar cell absorbs sunlight, and their dominant presence is the reason why a 2D TMDC solar cell has such high solar absorption. Electricity is produced by the solar cell when the positively and negatively charged components of an exciton are funneled off to separate electrodes.

By modeling the solar cells in this way, the team was able to devise a design with double the efficiency compared to what has already been demonstrated experimentally.

“The unique part about this device is its superlattice structure, which essentially means there are alternating layers of 2D TMDC separated by a spacer or non-semiconductor layer,” says Jariwala. “Spacing out the layers allows you to bounce light many, many times within the cell structure, even when the cell structure is extremely thin.”

“We were not expecting cells that are so thin to see a 12% value. Given that the current efficiencies are less than 5%, my hope is that in the next four to five years people can actually demonstrate cells that are 10% and upwards in efficiency.”

Jariwala says the next step is to think about how to achieve large, wafer-scale production for the proposed design. “Right now, we are assembling these superlattices by transferring individual materials one on top of the other, like sheets of paper. It’s as if you’re tearing them off from one book, and then pasting them together like a stack of sticky notes,” says Jariwala. “We need a way to grow these materials directly one on top of the other.”

June 6, 2023 By Editor

Rolling blackouts are costing South Africa dearly. The electricity crisis is a barrier to growth, destroys investor confidence and handicaps almost every economic activity. It has raised input costs for producers and retailers, and has triggered a new round of inflation and interest rate increases.

Any solution will obviously incur cost because it will require the adoption of new technologies, such as large-scale grid-connected solar farms that are linked to battery energy storage. But these technologies are expensive. A solar farm consisting of 50 MW of photovoltaic panels with 240 MWh of storage capacity will cost R2.6 billion. Batteries are the biggest outlay, accounting for about 40% of the total cost.

A photovoltaic panel converts solar energy to electricity, which can be used to charge a bank of batteries or supply consumers directly. The batteries then supply the stored energy into the grid over peak periods.

Combining solar with storage makes it more expensive than coal—which still accounts for 80% of South Africa’s electricity generation— when comparing units of energy produced. But this technology is affordable relative to the options consumers are already adopting in significant volumes—diesel generators or small-scale batteries coupled to inverters—as long as it is at large scale and is used for peak power only.

I argue that South Africa can solve much of its energy crisis by building new facilities consisting of battery storage with photovoltaic panels. However, the new technology cannot be used without reform of the wholesale energy market.

Much of the media’s attention to the energy crisis has been focused on generation capacity, or lack thereof. But there is another equally important contributor—the failure by the government to unbundle Eskom (the state-owned electricity utility) and create a market operator and a transmission system operator as independent entities.

A market operator is an energy “stock exchange”. It facilitates contracts between the energy producers, the transmission system and the distributors. Many countries in the world have already restructured their electricity supply industry to establish such a market and introduce greater competition among the power producers.

The UK, Canada, the US and many countries in the European Union have undertaken market reforms like this, with positive outcomes.

South Africa indicated an intention to follow such an approach in 1998. But it has never acted on this policy. Instead, it has kept alive an increasingly inefficient and dysfunctional state-owned utility. As a result, the country has a shortage of generation capacity, a shortage of connection and transmission capacity, and a growing environmental disaster.

Analysis of the usage data from the Eskom portal suggests that rolling power blackouts have led to changes in the country’s energy landscape.

On the supply side, customers are increasingly using alternative energy sources. Consumers who require stable energy supply have made alternative plans, in most cases shifting to the use of diesel generators. Figures of diesel consumption are not available, but, based on the electricity shortfall, I estimate, using the data for April 2023, that the additional diesel usage, excluding Eskom and the independent power producers, was about 660 million liters per month, which is almost the same as the amount used by the whole transport sector.

On the demand side, the blackouts have led to shifts in the use of grid electricity at a different time of the day/night cycle. This has been driven mainly by the use of lithium batteries. Eskom is already reporting that there is an added demand of 1.4GW to recharge battery storage, or about 5% additional load on the grid.

The cost of a battery-plus-inverter system to meet the needs of an average household under Stage 4 loadshedding—which is about 6 hours of outages every 24 hours—is about R100,000 to R150,000 (about US$5,000 to $7,600). At current interest rates, and assuming an average energy consumption of 15kWh per day and an Eskom rate of R2.75 per kWh, the net cost will be R6.10 per kWh. This makes it more expensive than diesel.

Back-up power from an 8kVA diesel generator, using the same set of assumptions, will cost about R5.20 per kWh, including diesel and capital charges.

The installation of 1.4GW of battery capacity nationally confirms that there is already a market for the purchase of energy at higher cost. Energy security is a necessity for many businesses, especially those operating cold storage or essential equipment.

In a recently published article I set out what the landscape might look like if South Africa implemented a plan to balance renewable energy capacity and time-of-use tariffs, and ended Eskom’s monopoly.

Customers could pay different rates depending on the time of day when they used electricity.

For my article, I used a simple model for the South African energy grid and considered the optimal configuration for a photovoltaic/battery storage facility which could provide peak power of 6GW, which is about 20% of the total demand.

It concluded that the grid would need an installed photovoltaic capacity of 18GW, coupled with a storage system rated at 3.7GW/10.4 GWh. The facility would pay for itself if a time-of-use tariff of R3.50 per kWh, almost double the present tariff excluding network charges, could be levied.

But this would require ending Eskom’s distribution monopoly and the establishment of the market operator. Different tariffs would be the result of competition between different players.

The analysis suggests that it would be possible to solve the peak power problem in three steps. Firstly, unbundle Eskom and establish the market operator, secondly use the bail-out funds to build connection capacity, and thirdly, use the market operator to build large-scale photovoltaic/battery capacity. Market reform has been on the policy agenda for nearly 25 years. But little real progress has been made. South Africa should stop going around in circles. It needs to take a straight line in the fast lane.

June 5, 2023 By Editor

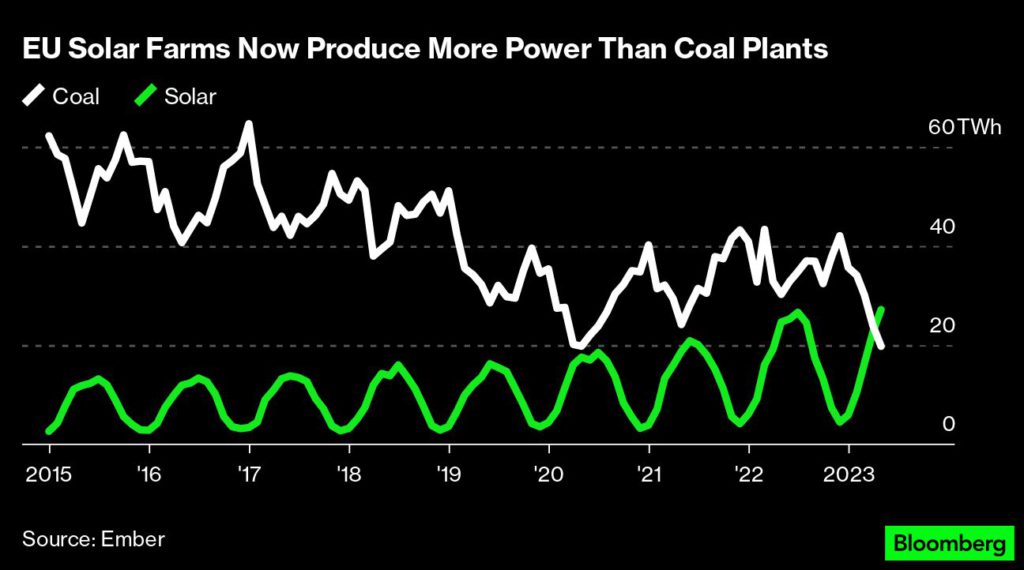

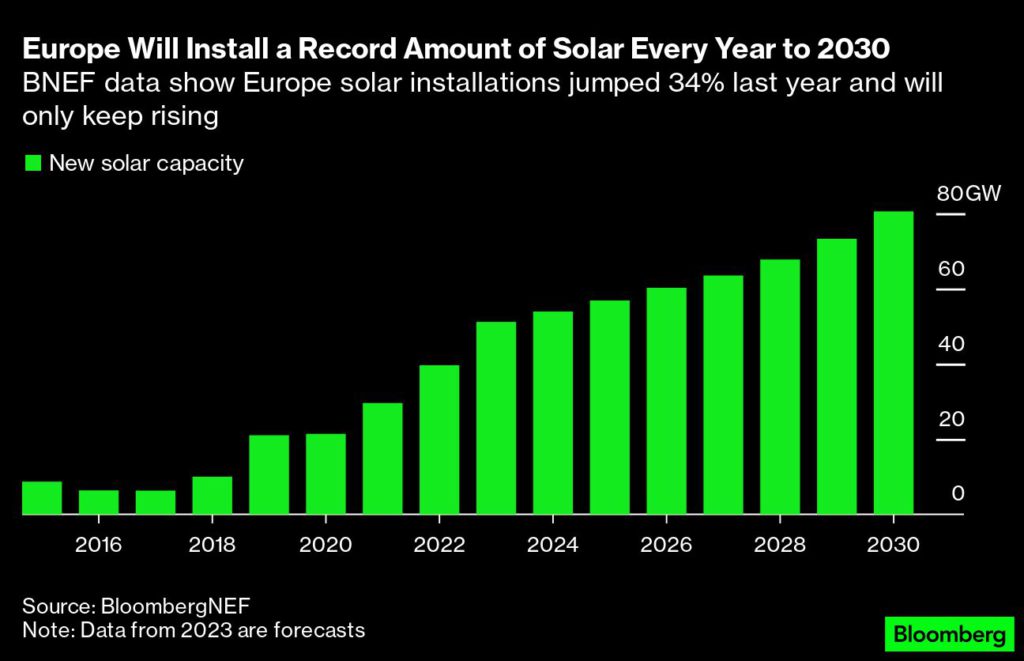

The European Union’s transition to clean energy marked a milestone in May, when solar panels generated more electricity than all of the bloc’s coal plants for the first time — and that’s before summer sun boosts production even further.

While the furious expansion of solar generation bodes well for efforts to replace fossil fuels, the breakthrough also exposed flaws in the energy system. Power prices turned negative during some of May’s sunniest days as grid operators struggled to handle the surge.

“This summer will be something we’ll have to look at like it’s a postcard from the future,” said Kesavarthiniy Savarimuthu, analyst at BloombergNEF. “The biggest message will be: we’re not ready.”

Although solar was a fast and easy solution to respond to last year’s energy crisis triggered by Russia’s moves to squeeze natural gas supplies, the downside is the technology is best in sunny months when demand is typically lower. Systems to store that energy in batteries or by creating green hydrogen aren’t advanced enough to allow the summer sun to keep lights on at night or help heat homes in the winter.

Nowhere is the solar boom — and the adjustment risks — clearer than in the Netherlands. There are over 100 megawatts of solar panels for every 100,000 Dutch residents, double the deployment of sunny Spain and more than triple the rate in China — by far the global leader in total solar capacity.

The Netherlands’ claim to the densest solar network on Earth is thanks largely to long-running government support. The program rewards households for installing solar panels, with every watt of electricity offsetting energy bills, regardless of whether usage matches up with the sunniest parts of the day.

“The Dutch government did this to stimulate solar panels, but it’s a little too successful,” said Jorrit de Jong, spokesman at Dutch electric grid operator TenneT, who has seven roof-top solar panels that produce at least 80% of his annual household electricity consumption. “If I do my laundry or charge my car at moments when there isn’t sun, it doesn’t matter for me because I get paid by my energy company.”

The government in the Netherlands plans to change the system starting in 2025. Under new rules, households that send power back to the grid would be able to deduct a declining amount from their annual bill. By 2031, producers would only benefit from power they actually consume and not get compensated for any excess.

Across Europe, people are following the Dutch example. Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, installations of solar panels in the EU have accelerated. In May, production rose 10% compared to the previous year to reach a record 27 terawatt hours.

In contrast to wind, hydro or geothermal power, solar has a key advantage of being quick to install. All it takes is an incentive for homeowners or property companies to turn roofs into mini energy parks. But electricity grids were set up around massive generators that could work in tandem with grid operators to keep networks balanced. A more distributed system is harder to manage and will be tested in earnest this summer.

While record solar and wind production have helped drive out coal and gas plants at an impressive rate this year, the EU still has a long way to go to reach its goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. Germany is under even more pressure, with Europe’s biggest power market aiming for a decarbonized grid by 2035. Getting there will require not only a massive expansion of clean energy, but also changes that better align consumption with generation.

There are already signs of a mismatch between supply and demand. Last weekend, electricity prices turned negative at times as solar output hit a record in Germany, Europe’s biggest producer. Negative prices aren’t unheard of and are typically linked to strong wind generation at night or on weekends when demand is thin.

When there’s a surge in power, suppliers have to pay consumers to use electricity. It doesn’t mean 100% of the power is coming from renewables. Some conventional plants can’t flexibly switch on and off or are required to run to maintain grid stability.

Increasing price swings and persistent low or negative rates during peak production periods for renewable power could put further investment at risk, according to Axel Thiemann, chief executive officer of Sonnedix, one of Europe’s biggest solar developers.

Since the end of 2021, Sonnedix has roughly doubled its pipeline of European projects, but Thiemann warned development will get more difficult without changes to how power is managed.

“As more investment gets realized, the grid will get more and more saturated during certain parts of the day in the summer,” he said in an interview. “Even if you have unlimited amounts of solar projects that are permitted, they will not be built unless there’s a clear route to market.”

Better coping with the ebb and flow of renewable generation will require a new kind of flexibility in the power system, which wasn’t necessary when all electricity came from a few giant fossil fuel and nuclear plants that could be turned up or down depending on demand.

“Our current power system wasn’t planned for these kinds of flexibility needs,” said Thorsten Lenck, project manager at Berlin-based think tank Agora Energiewende.

There are various ways to adapt. Batteries connected to the grid could use power during the sunniest or windiest parts of the day to sell when renewables aren’t producing as much. Consumers could also be incentivized to use power during times of peak production. That could be particularly important as more electric vehicles hit the roads and households switch from traditional boilers to heat pumps.

“We’re going to have an unprecedented amount of solar production this summer and it tends to increase the volatility in power prices,” said Joke Steinwart, analyst at Aurora Energy Research. “This presents big opportunities for flexible technologies like batteries.”

June 4, 2023 By Editor

On 7 March 2023, just as the European Council was preparing to vote on a ban on the sale of new internal combustion engine cars in Europe from 2035, something went wrong: Germany, whose vote was essential for the measure to be approved, and a coalition of six other European countries blocked the vote on the text, pushing the legislation back indefinitely.

A few days later, the European Commission, representing all the member countries, unveiled its response to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Net-Zero Industry Act, a competitiveness plan based on accelerating the green transition.

Amid all the political back-and-forths, one would be forgiven for asking oneself whether Europe is making any progress with the green transition. It would appear the European Union (EU) has become Janus, with a pro-transition face and a procrastinating face, just as a pro-competition face contrasts with a protectionist face. The consequence of such contradictions is a loss of credibility when it comes to achieving its objectives, and a delay in the race toward ecological transition.

Yet the EU seemed well on the way to establishing itself as a world leader in the transition, with its dynamic green ecosystem made up of innovative businesses supported by the “European Climate Bank,” as the EIB (European Investment Bank) likes to call itself. At the end of February, the EIB reaffirmed its intention to champion green initiatives by channeling the vast majority of its funds toward the transition, beyond the already honorable level of 60% achieved by 2022.

The EU also seems to be particularly ahead of the game on green hydrogen, boasting a number of important projects of European interest (IPCEI), the world’s leading number of patents (ranking last January by the International Energy Agency) and an embryonic hydrogen bank.

This position is confirmed by foreign investors who find themselves attracted to the bloc’s green policies and regulatory clout. Take the latest Border Carbon Tax Mechanism (CBAM), which is set to place a carbon price on imports entering the European single market from non-EU countries from this autumn: It is a textbook example of how to take into account negative ecological impacts while respecting competition thanks to the price signal. The recent revaluation of the price of a tonne of CO2 above 100 euros suggests that it will be very effective indeed.

That’s if we don’t undermine it with exemptions and deferrals sine die, or disguised pollution subsidies such as France’s energy “tariff shield”). According to the IEA, Europe spent nearly 350 billion euros on such measures in 2022—a record high.

To give businesses and investors the certainty that the EU won’t be going backwards, we need to set clear, consistent targets and stick to them. It is essential to anchor players’ expectations on a fixed and certain horizon so that markets can be challenged, competition can be triggered, and private investment can flow. Any form of renunciation by the EU will discourage players from speeding up the transition and will cause those who were ahead of schedule in reaching the 2035 horizon to backpedal.

To remain competitive, French carmaker Renault has focused its clean-car strategy on its electricity division and split its activities into five divisions—Ampere (clean vehiciles), Power (thermal and hybrid motors), Alpine (sport), Mobilize (new forms of mobility) and The Future Is Neutral (circular economy). Power is intended to be supported in part by the profits from the project “Horse,” which involves a joint venture with the Chinese carmaker Geely.

Stellantis—the parent company of Chrysler as well as European brands such as Peugeot, Citroën, Fiat and and Alfa Romeo—has also positioned itself in the premium segment of the clean-car market, alongside other players such as Tesla of the US and French energy giant TotalEnergies, which is equipping its service station network with recharging stations. These moves demonstrate the decisive role of competition in developing a range of products and services in line with the imperatives of the energy transition.

Open markets allow new players to join or withdraw on terms that suit them, thus fostering competition and innovation. This virtuous circle is essential to overcoming the technological frontier of transition—the most advanced level of research at a given time—and get a jump on tomorrow’s solutions. In theory, an economy that’s open to competition leads to sophistication in the value proposition of offerings and to shared value for all: quality of service and lower prices to the benefit of demand greater returns on innovation and scale and attraction of scarce resources to the benefit of supply.

The longer the European Union postpones its objectives and gives in to protectionist pressures, the longer it will be locked into what former Canadian central banker Marc Carney has called the tragedy of the horizon, and so the more it will fall behind its rivals. The EU would benefit from remaining consistent with its founding principle of competition and its four fundamental freedoms (movement of goods, capital, services and people) to attract the capital needed for the transition and the infrastructure essential for its spread (such as electric charging stations) and acceptability.

At a time when the United States has strayed into protectionism, the EU must stand firm on its commitments and remain faithful to competition, the virtues of which will accelerate the transition and its spread with accessible solutions. It’s time to move on from “greenwishing”, as the American economist Nouriel Roubini called it ironically, to green-enacting thanks to a winning combination of competitiveness and attractiveness.

June 3, 2023 By Editor

As we race to decarbonize by electrifying everything, solar panels—now cheaper per square meter than marine-grade plywood—will do much of the heavy lifting. But if we don’t rethink how our rooftop panels plug into the grid, the transition will be unfair and costly—for both people who own solar panels (and electric cars and smart appliances) and people who don’t.

Australia has the world’s highest solar installation rate per person. When solar panels generate more energy than a household is using, the excess electricity can be exported to the grid. Rooftop solar regularly provides more than a quarter of daytime electricity across the National Electricity Market. At times it exceeds 90% in South Australia.

The amount of solar in our grids is affecting how the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) and distribution businesses (which own the powerlines) keep the lights on. The measures in place are costing households that are generating solar power, but also non-solar owners and network operators. So how can we make the system fairer for all?

We suggest solar panels should be thought of a little more like apple trees. If you have a tree in your backyard you should be able to use as many apples as you produce. But selling apples for profit creates extra responsibilities, along with uncertainties about supply and the fair selling price.

Our new research paper, published in The Electricity Journal, outlines principles for fairness and proposes a bill of rights and responsibilities for connecting to the grid.

What’s not fair about the current system?

At times, the amount of solar energy being exported can be too much for the network to handle.

That’s why inverters (the box on the side of a house with solar panels) have settings that automatically reduce exported electricity when network capacity is under strain. Other mechanisms are also being put in place to allow AEMO to occasionally curtail output from rooftop solar to maintain power system security.

However, such measures not only reduce how much electricity is flowing from a home to the grid, but the entire output of the home’s rooftop system. There aren’t any fundamental reasons for this, just that appropriate inverter and control settings haven’t been enabled.

But this means a household, at times, can’t use any of the electricity it’s generating. In South Australia, the annual cost to customers of this sort of curtailment is already between A$1.2 million and A$4.5 million. This isn’t fair.

But it also isn’t fair when solar owners get paid to export electricity when prices are negative—that is, when other generators must pay to keeping exporting to the grid. This is happening more often, totaling more than half of all daytime hours in SA and Victoria last quarter.

Nor is it fair for distribution businesses to build more poles and wires to accommodate everyone’s solar exports all the time. Or if the system operator has to buy more reserves to cover for the uncertainties of rooftop solar output.

In these instances, all customers foot the bill whether they own solar panels or not. But non-owners are hit hardest when the costs of such measures are passed on. People without rooftop solar are completely exposed to the 20-25% electricity price rises from July 1.

Some solar owners will hardly notice the increase.

Australia’s electrification will replace fossil fuels to run households, businesses, vehicles and industry. It’s expected rooftop solar will increase five-fold. How should households with these growing distributed energy resources interact with the grid in future?

We reckon the social contract for grid electricity needs to evolve from the pay-plug-play expectations dating from the 19th century to a two-way engagement to support fairness for all.

To return to the apple tree analogy, if you have a tree in your backyard you should be able to eat as many apples as you’d like, and make crumble, cider, whatever. But selling apples for profit comes with a responsibility not to carry codling moth. And selling crumble or cider is subject to food safety and licensing requirements.

And the prices? That depends on the availability of trucks and local market value. Maybe you or our government could pay more for trucks for everyone to be able to sell apples all the time, but it probably wouldn’t be efficient or fair.

The main distinction we draw is between growing for yourself and selling for profit. The analogy obviously isn’t perfect. Apples aren’t an essential service, apple trucks aren’t a regulated monopoly, and the supply and demand of apples doesn’t need to be balanced every second.

However, the principles remain—especially for a future where apple trees (rooftop solar) and apple warehouses (home batteries and electric vehicles) are everywhere.

In our research paper we distinguish between rights for passive use (using your own rooftop solar electricity) and responsibilities for active use (selling electricity).

No-one should be able to stop you using your own self-generated electricity (for the vast majority of the time). But making money from the grid will likely come with responsibilities to allow trusted parties such as network operators to manage your exports at times (a system known as flexible export limits).

If you’re charging and discharging batteries for profit, you will likely have a responsibility to provide some visibility of your expected use to help the operator manage the grid.

In a country with lots of solar energy, prices for selling energy mightn’t be guaranteed all the time either.

We must think about this new social contract. If we don’t, electrifying everything will be harder, more expensive, less fair and more reliant on large-scale projects requiring new transmission lines, which are complex and costly to build.

The story of distributed electricity is incredible—the power is literally in our hands when we flick a switch, grab the wheel, buy a product. We have an opportunity now to make it work better and be fairer for all of us.