‘Limitless’ energy: How floating solar panels near the equator could power future population hot spots

News and Information

August 5, 2023 By Editor

August 4, 2023 By Editor

With air conditioner demand surging, scientists are looking for ways to improve the energy efficiency of cooling systems and limit damaging emissions that accelerate global warming.

Innovation is focused on three major fronts, with much of the attention on energy consumption. Air conditioning units account for six percent of electricity used in the United States.

Several breakthroughs have already cut power consumption by half since 1990, according to the US Department of Energy.

The most impactful was the so-called “inverter” technology, which makes it possible to modulate the motor’s speed instead of running it at 100 percent continuously.

Other new features include demand controlled ventilation (DCV), which relies on sensors to determine the number of people in the building and adjust airflows.

Another major area is the search for substitutes to the refrigerant gases used in most of the nearly two billion installed AC units, according to the International Energy Agency.

For decades, air conditioners almost exclusively ran on chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) or hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) gases, which are thought to be up to 10,000 times as bad as CO2 in terms of global warming impact.

CFC and HCFC were banned under the Montreal Protocol, from 1987.

Then came hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are now scheduled to be phased out by 2050.

Factories and commercial buildings already use other gases, such as ammonia—which has no greenhouse gas impact—as well as hydrocarbons, mainly propane, whose emissions are lower than methane.

“In some countries, you’re starting to see hydrocarbon refrigerants,” mostly propane, “being used, but there are restrictions around how much quantity you can put into the system” because such gas is flammable, said Ankit Kalanki, manager at the Rocky Mountain Institute.

Mandatory safety features make for a “level of sophistication” with “a price premium that gets added to the units itself,” he added.

“And the residential air conditioning market tends to go towards the lowest first cost products, then the highest efficiency products.”

Some are trying to go gasless, like Pascal Technology, a Cambridge, Massachusetts startup, that’s working on a mechanism to keep refrigerants in a solid state, avoiding any discharge.

Other innovation is focused on products that bypass compression, an energy-intensive process in air conditioning that has changed little since its invention in 1902.

Separate groups of scientists at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, respectively have built air conditioners that use water to cool the air.

The Wyss Institute has already made prototypes based on its cSNAP model, that operates on a quarter of the electricity used in the traditional compression process.

The device is partly built with ceramic panels, made in Spain.

The startup Blue Frontier, which counts Bill Gates as an investor, uses a salt solution that captures the humidity of the air, then cools it through contact with water.

The solution also makes it possible to store energy, “so you’re not having to deal with capacity limits of the infrastructure,” said Daniel Betts, Blue Frontier’s CEO.

The Florida-based startup plans to rent its AC units to commercial building owners for a subscription fee, recouping its investment from electricity savings.

Usually, acknowledges Betts, “building owners don’t see the value, except for marketing, of having higher efficiency equipment.”

“We eliminate the burden of financing high efficiency equipment, because we’re doing it as a subscription service.”

Air conditioning innovation has been slower to address the third major issue related to conventional units, the discharge of hot air outside buildings.

One of the few available options are geothermal heat pumps, which employ a grid of buried pipes that channel cooler temperatures from underground, and do not release warm air.

August 3, 2023 By Editor

They are ubiquitous in the United States, controversial in Europe and coveted in South Asia. As heat waves intensify across the world, air conditioning has taken center stage.

For better or for worse, these power-hungry appliances are among the most common adaptations to a warming world. They have become a necessary tool for the survival of millions, according to experts.

But while they bring immediate, life-saving relief, air conditioners come at a cost to the climate crisis because of their enormous energy requirements.

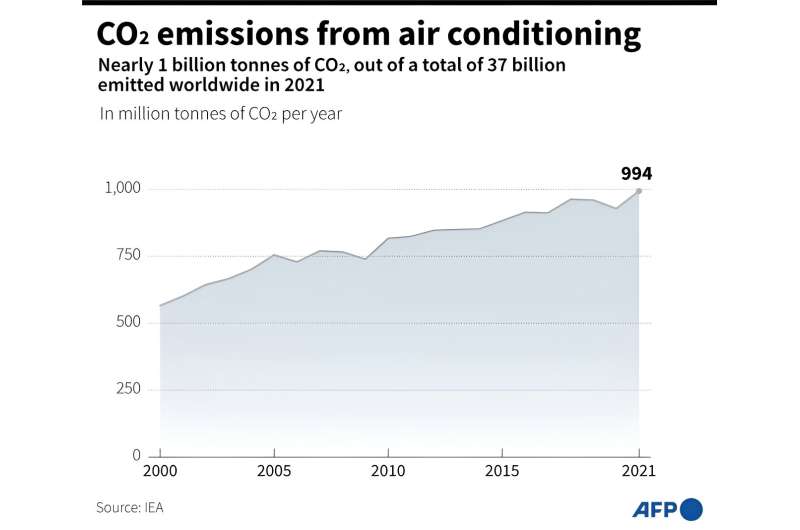

Air conditioning is responsible for the emission of approximately one billion metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), out of a total of 37 billion emitted worldwide.

It is possible to end this vicious cycle, experts say, by increasing the contribution of renewable energies, developing less energy-intensive air conditioners and augmenting them with other cooling techniques.

“There are some real purists who think that we can eliminate, but I just don’t think that’s feasible,” Robert Dubrow, a Yale epidemiologist who specializes in the health effects of climate change, told AFP.

Access to air conditioning already saves tens of thousands of lives a year, a figure that is growing, according to a recent IEA report co-authored by Dubrow.

Studies show that the risk of heat-related death is reduced by about three-quarters for those living in homes with an air conditioner.

In the United States, where about 90 percent of households have AC, studies have highlighted the role of air conditioning in protecting the population—and the potentially devastating effect of widespread power cuts during heatwaves.

But globally, of the 3.5 billion people living in hot climates, only about 15 percent have air conditioners at home.

The number of air conditioners in the world, about two billion today, is set to skyrocket as temperatures and incomes rise.

India, China and Indonesia—the first, second and fourth most populous countries in the world—are among those that will see the strongest growth.

By 2050, the share of households in India equipped with air conditioners could increase from 10 to 40 percent, according to a recent study.

But such an increase in electricity consumption would be equivalent to the current total annual production of a country like Norway.

If India’s future grid uses as much fossil fuels as it does today, that would mean around 120 million tons more carbon dioxide emitted annually—or 15 percent of the country’s current energy sector emissions.

The problems posed by increased air conditioning do not stop there. Running power plants also causes air pollution.

Air conditioners also generally use fluorocarbon gases as refrigerants, which have a warming power thousands of times greater than CO2 when they escape into the atmosphere.

And by discharging their hot air out into the streets, air conditioning contributes to urban heat island effects.

A 2014 study found that at night heat emitted from air-conditioning systems in city centers increased the mean air temperature by more than 1 degree Celsius (almost 2F).

Finally, due to its cost, access to air conditioning poses a major equity issue.

Once installed, the price of the electricity bill can force families to choose between cooling and other essential needs.

For Enrica De Cian, a professor in environmental economics at Ca Foscari University in Venice, the use of AC is “an important strategy in certain conditions and in certain places.”

But, she adds, it’s essential to combine it with “complementary” approaches.

First, by continuing to ramp up renewable energy production, and wind down fossil fuels, so that energy used by air conditioners leads to fewer emissions.

Second, by developing and installing affordable air conditioners that consume less energy, which some companies are working on. The IEA advocates for stricter efficiency standards, but also recommends air conditioners to be set at a minimum of 24C (75F).

Beyond limiting emissions, greater efficiency would also curb the risks of power cuts linked to excessive demand. On hot days, air conditioning can account for more than half of peak consumption.

But above all, the experts hammer home the simultaneous need for spatial planning measures: including more green spaces and bodies of water, sidewalks and roofs that reflect the Sun’s rays, and better building insulation.

“We have to achieve sustainable indoor cooling,” said Dubrow.

The proposed solutions are “very feasible,” he adds. “It’s a matter of political will for them to be implemented.”

August 2, 2023 By Editor

The US has some of the most potential for offshore wind energy in the world, says a new analysis by the University of California, Berkeley. Offshore wind resources are plentiful enough to generate up to a quarter of the nation’s electricity by 2050, in time to help meet global climate goals.

It will take a monumental effort to reach those goals, with very little offshore wind capacity installed in the US today. And the industry is currently facing mounting political and financial challenges even after the Biden administration moved to open up much of the country’s shoreline to offshore wind development.

But the report shows what’s possible in the long run if the US can harness the power of those winds at sea. “The good news about this offshore wind potential is it is spread out across the country from the East Coast, West Coast to the Gulf, as well as the Great Lakes region,” Nikit Abhyankar, senior scientist at the University of California, Berkeley Center for Environmental Public Policy, said in a press briefing last week. “This will be a critical resource to diversify our clean energy supply.”

To limit global warming to the thresholds outlined in the Paris agreement, countries need to bring greenhouse gas emissions down to net zero by 2050. The US, as the biggest historical greenhouse gas polluter, has a huge role to play if the world is to succeed in mitigating wildfires, heatwaves, droughts, and floods made worse by climate change. The Biden administration has committed to halving the nation’s emissions by the end of the decade and has plans to source electricity completely from carbon pollution-free energy by 2035.

Adding to that urgency, US electricity demand is forecast to nearly triple by 2050, according to the Berkeley report. On top of a growing economy, the clean energy transition means electrifying more vehicles and homes — all of which put more stress on the power grid unless more power supply comes online at a similar pace.

To meet that demand and hit its climate goals, the report says the US has to add 27 gigawatts of offshore wind and 85 GW of land-based wind and solar each year between 2035 and 2050. That timeline might still seem far away, but it’s a big escalation of the Biden administration’s current goal of deploying 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030. Europe, with an electricity grid about 70 percent the size of the US, already has about as much offshore wind capacity as the Biden administration hopes to build up by the end of the decade.

Right now, wind energy makes up just over 10 percent of the US electricity mix, and nearly all of that comes from land-based turbines. Installing turbines at sea can get more complex and expensive. You need specialized ships built to handle skyscraper-sized turbines, for instance. And companies are still developing floating turbines needed to one day master deeper ocean depths on the West Coast.

For now, the US has just two small wind farms off the coasts of Rhode Island and Virginia. Construction started on the foundations for the nation’s first commercial-scale wind farm off Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, in June.

Many plans for offshore wind farms in the US, however, are facing tough headwinds. There’s growing opposition from some coastal communities, the fishing industry, and some Republican lawmakers who’ve tried to tie east coast whale strandings to offshore wind development without any evidence connecting the two.

Project costs have gone up with higher interest rates and rising prices for key commodities like steel, Heatmap reports. That’s led to power purchase agreements falling through for some projects in early development, including plans in Rhode Island for an 884-megawatt wind farm that alone would have added more than 20 times as much generation capacity as the US has today from offshore wind. Developers are struggling to make projects profitable without passing costs on to consumers.

The Berkeley researchers, who worked with nonprofit clean energy research firm GridLab and climate policy think tank Energy Innovation, are more optimistic. The study found a modest 2 to 3 percent increase in wholesale electricity costs with ambitious renewable energy deployment. But renewable energy costs have fallen so dramatically in the past that the researchers think those costs could wind up being smaller over time.

“The industry has always proven all the researchers wrong, including ourselves, in the past. So we do believe the cost impact will not be a major factor going forward in the long run,” Abhyankar said in the press call.

There are typically stronger winds blowing over the smooth ocean surface compared to land, the potential payoff for offshore wind developers if they can get past the startup costs. Plus, offshore wind complements land-based renewables, the report points out, since it can fill in for solar panels at night. On the West Coast, offshore wind potential peaks in the summer and in the evening when electricity demand for home air conditioning rises. On the East Coast, winds pick up in the winter — just in time to meet added demand for heating if more homes and buildings go all-electric. It’s the clean energy dream that’s going to take a lot more work before it can become reality.

August 1, 2023 By Editor

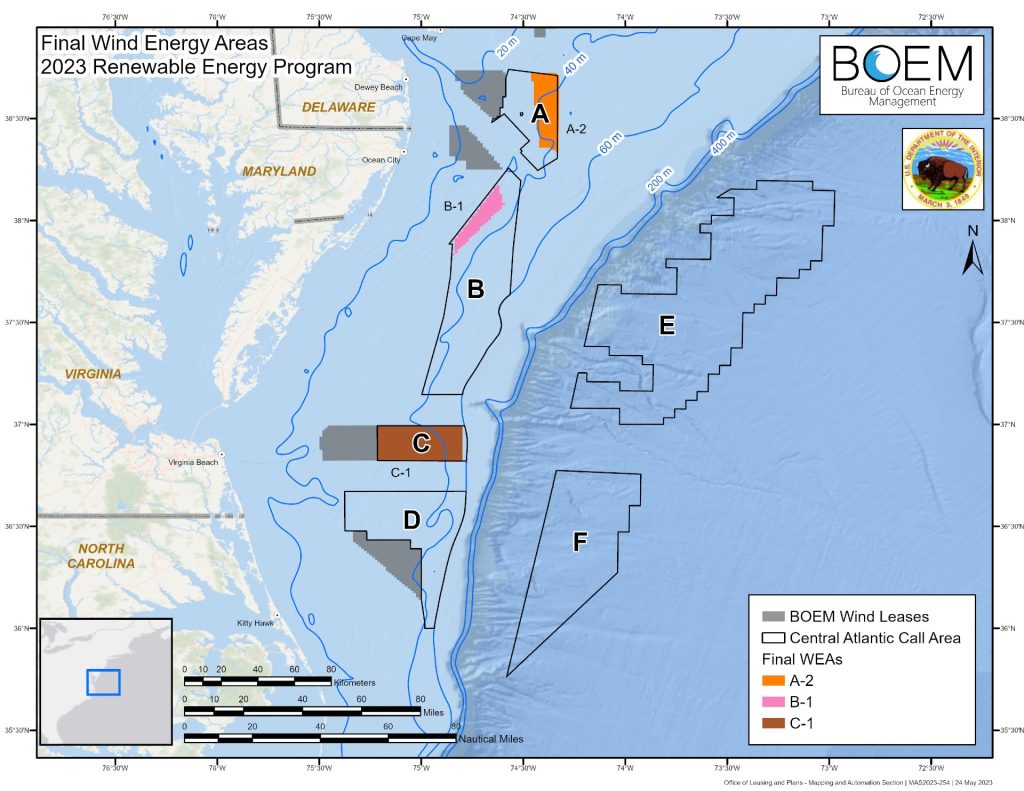

The US government today designated three new offshore wind areas in the Central Atlantic that could potentially host 4 to 8 gigawatts (GW) of clean energy production.

The US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s (BOEM) three new Wind Energy Areas (WEAs) are off the coasts of Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia.

The WEAs together total about 356,550 acres:

BOEM says the three WEAs were developed following “extensive engagement and feedback from states, Tribes, local residents, ocean users, federal government partners, and other members of the public.” It says it may identify additional WEAs in deep-water areas off the US Central Atlantic coast for future leasing once further study of the areas is complete.

July 31, 2023 By Editor

An increasing number of countries are exploring the potential to develop their geothermal energy capacity as governments look to expand their energy portfolios to include a broader range of renewable sources. As the U.K. assesses its deep geothermal potential, a major Japanese utility is betting big on geothermal energy in Germany, and Kenya is taking a regional approach to developing capacity. Greater investment in the sector is expected to continue supporting technological breakthroughs to draw investor interest and make operations more economically viable.

Geothermal operations use steam to produce energy. This steam is derived from reservoirs of hot water, typically a few miles below the earth’s surface. The steam is used to turn a turbine, which powers a generator to produce electricity. There are three varieties of geothermal power plants: dry steam, flash steam, and binary cycle. Dry steam power plants use underground steam resources, piping steam from underground wells to a power plant. Flash steam is the most common form, using geothermal reservoirs of water with temperatures above 182°C. The hot water travels through wells in the ground under its own pressure, which lessens the higher it travels to produce steam to power a turbine. Finally, binary steam power plants use the heat from hot water to boil a working fluid, typically an organic compound with a low boiling point, which is then vaporised in a heat exchanger and used to turn a turbine.

British Geological Survey (BGS) and Arup, a British engineering consultancy, recently developed a White Paper entitled ‘The case for deep geothermal energy — unlocking investment at scale in the UK’, funded by the U.K. government. It aimed to assess the opportunities for constructing deep geothermal projects across the country to help diversify Britain’s renewable energy mix. To develop deep geothermal systems, companies must drill deep wells to reach higher-temperature heat sources at depths of more than 500 m. There is significant potential to develop these resources in the U.K., but the complex drilling operations come at a high cost, which has so far deterred developers.

However, as technologies are improving, thanks to greater funding for research and development in the renewable energy industry, the number of areas where geothermal exploitation is economically viable is expected to increase. Most of the U.K.’s deep geothermal resources can be found in deep sedimentary basinsacross the country. The White Paper recommends that the government promotes geothermal energy as one of the U.K.’s renewable energy resources to boost investor confidence and promote awareness of the energy source. The establishment of a regulatory body could also support the development of new projects, while a licensing system could help streamline future projects.

In Japan, one of the country’s biggest utility groups, Chubu Electric Power, announced plans to buy into a geothermal energy project in Germany. Chabu is purchasing a 40 percent stake in the company, which plans to develop first-of-its-kind geothermal power and district heating project in Bavaria. It will use Eavor-Loop technology developed by Canadian start-up Eavor, transforming sub-surface heat from the Earth’s core into renewable energy, without the need to discover underground hot-water reservoirs. Chabu already invested in Eavor itself in 2022 and hopes to promote the commercialisation of the new technology in Germany.

Meanwhile, in 2022, Kenya – which drilled its first geothermal well in the 1950s and opened its first power plant in 1981, came seventh in the world for geothermal energy production. Kenya produces around 47 percent of its energy from geothermal resources. It is one of only two African countries, alongside Ethiopia, that produces geothermal energy. The East African country hopes to assist neighbouring states with their geothermal ambitions, in a bid to support the regional development of clean energy resources in line with the global green transition. KenGen, the government entity that operates Kenya’s geothermal power plant, is providing technical support to other countries in the region, having already drilled multiple geothermal wells in Ethiopia and Djibouti to assess their potential.

And this month, the governments of Indonesia and New Zealand confirmed their cooperation in geothermal energy projects. Indonesia-Aotearoa New Zealand Geothermal Energy Program (PINZ) has been extended for 2023-2028, with a funding commitment of $9.9 million from the New Zealand government to develop Indonesia’s geothermal industry. This partnership has existed for over a decade, to support Indonesia’s clean energy transition.

Several governments around the globe are increasing their investments in research and development into geothermal energy, aiming to diversify the renewable energy mix and reduce reliance on any single energy source. Investment into geothermal energy technology in recent years has already led to advancements that are expected to make new operations more economically viable, with further breakthroughs expected to come as the global geothermal market is established.