Researchers find inconsistencies in studies evaluating small hydropower projects

News and Information

October 14, 2022 By Editor

October 13, 2022 By Editor

Experimental technology used to cool equipment in space might soon be able to cut the charging times of electric vehicles to five minutes or less, American space agency NASA said this week.

The federal space agency-funded technology, in partnership with Purdue University, says the research they’re planning for future space missions shows its tech could charge an electric car within minutes instead of hours, according to an Oct. 5 blog by NASA.

Using a technique known as “subcooled flow boiling,” the tech could boost the amount of electrical current EV chargers by roughly 1,400 amps, nearly five times the rate of up to 520 amps currently supplied to EVs, NASA said.

Standard EV chargers that consumers can buy tend to provide less than 150 amps, the blog added.

The potentially new system could be used to “deliver 4.6 times the current of the fastest available electric vehicle chargers on the market today by removing up to 24.22 kilowatts of heat,” NASA said.

A major question for EV skeptics solved?

What does that mean? NASA and Purdue researchers may have solved a longstanding question for those who want an EV, yet have concerns about how long it may take to charge it.

Usually, it takes EVs about 20 minutes to charge at a roadway station to possibly several hours using an at-home charging station, NASA and Purdue researchers say.

“This same technology may make owning an electric-powered car here on Earth easier and more feasible,” the blog said. “Application of this new technology resulted in (an) unprecedented reduction of the time required to charge a vehicle and may remove one of the key barriers to worldwide adoption of electric vehicles.”

EV sales expected to hit ‘all-time high’ in 2022

The news from NASA comes as electric vehicle sales are on track to hit an all-time high this year, according to the International Energy Agency’s recently released Tracking Clean Energy Progress update.

The agency said worldwide sales of EVs doubled in 2021 to represent nearly 9% of the car market and expects record sales this year “lifting them to 13% of total light-duty vehicle sales globally.”

NASA said the technology that could charge EVs faster was developed to bring “nuclear fission power systems for missions to the moon, Mars and beyond.”

It could also fuel “vapor compression heat pumps to support Lunar and Martian habitats and systems to provide thermal control and advanced life support onboard spacecraft,” the agency said.

The “subcooled flow boiling,” can cool cables carrying high charges, possibly allowing for a faster flow of electricity without risking components overheating, NASA’s blog said.

EV cable charging research has been ongoing

Last year, Purdue engineers announced “an alternative cooling method” by inventing “a new, patent-pending charging station cable that would fully recharge certain electric vehicles in under five minutes—about the same amount of time it takes to fill up a gas tank.”

This research and development collaboration was funded by Purdue and the Ford Motor Co., dating back to 2017.

“Ultimately, charge times will be dependent on the power output ratings of the power supply and charging cable, and the power input rating of the EV’s battery. To obtain a sub-five-minute charge, all three components will need to be rated to 2,500 amperes,” Purdue researchers said in its announcement last year.

The school also said its prototype “also mimics all the traits of a real-world charging station: It includes a pump, a tube with the same diameter as an actual charging cable, the same controls and instrumentation, and it has the same flow rates and temperatures.”

And Purdue said a lab run by mechanical engineering professor Issam Mudawar intends to work with EV or charging cable manufacturers to test the prototype on EVs within the next two years.

October 12, 2022 By Editor

The coming wave of satellite constellations all need power, but solar panels built for space are extremely expensive and difficult to manufacture. Solestial is ready to change that with space-grade panels built using inexpensive, scalable processes, and it just raised $10 million to take its tech from lab to orbit.

The company, formerly known as Regher Solar, has its roots in years of academic research at Arizona State University into the possibility of achieving the performance of space-grade cells with the materials and methods used for terrestrial solar panels.

When TechCrunch last spoke to Solestial, it was at the prototype stage, demonstrating that its bare solar cell could withstand the harsh environment of space despite projected costs being one-tenth as much as standard “III/IV” category panels.

“That’s really the foundation of our product, a solar cell that isn’t afraid of radiation; it has this unique feature of self-curing radiation damage,” said CEO and co-founder Stanislau Herasimenka — referring to the low-temperature heat curing their cells undergo at 80 degrees C, which purges flaws created by radiation.

“But people don’t buy bare solar cells,” he continued.

Even if the cells themselves work as advertised, no one wants to have to assemble them into panels themselves. Solestial has to prove that not just its proprietary cells but the interconnects, extra-thin silicon substrate and other components can also survive 10 years in orbit.

That means a lot of tests are in order. Fortunately the funding and a lot of potential customers have come through to support the company in its quest to displace the costly dedicated in-space panels — because there’s no way enough of those could be built to support the number of satellites going up over the next decade.

Although the goal is 10 years in space, it is of course impractical to test out there for that long. So the full panel assemblies are undergoing accelerated stress testing, where they’re exposed to more intense and varied radiation than they would normally see out there, as well as rapid temperature shifts and things like that. This is commonplace in space work — it’s not like you can go to the moon to test stuff you need to go to the moon, so you do your best to simulate it on Earth.

“Our customers want to help us get flight heritage; we already delivered several small solar panels for demo flights, we expect lots over the next year,” Herasimenka said. This is in addition to the stress testing and working on the manufacturing process: “Customers also want to see we’re capable of mass producing this thing, that our tech can smoothly be transferred from pilot production to high-scale production.”

Mass production is on the roadmap for about two years from now, he added, at which point the company expects to be able to make tens of thousands of panels and hopefully supply future constellations and large-scale installations.

It won’t be cheap, which is why the seed round, which Herasimenka told me a year ago would be closed in a matter of months, instead took a year and is twice as large. “We were advised we needed more money, and I absolutely agreed with that, given the scope of what we’re doing. It’s hard tech, it’s early stage and we need to do additional validation work,” he said of the delayed raise.

The new round was led by Airbus Ventures, with participation from AEI HorizonX, GPVC, Stellar Ventures, Industrious Ventures and others. Solestial previously collected about $2.5 million in SBIR awards, but those are meant to validate the theory, not scale the company.

Though they’re just getting started, Herasimenka was confident they’ll be a major supplier of solar panels to the next generation of spacecraft, but that they intend to branch out and become a broader power provider — hence the name change from Regher Solar to Solestial. “It’s not like we hated the name, but we wanted one that better reflected our ambition to be a solar energy in space company. We don’t want to stay a boring solar panel manufacturer forever, so we wanted a name that will grow with us as a brand,” he said.

It may be two years at a minimum until the first batch comes off the production line, but Solestial is already looking past that horizon. A communications satellite may last 8-10 years, but what about larger craft in higher orbits? What about large-scale lunar mining operations? They’d welcome a space-hardened solar solution that doesn’t break the bank, but it’ll have to last 20 years or more. That’s the next strategic step for Solestial, but first it has to get its flagship product out the door.

October 11, 2022 By Editor

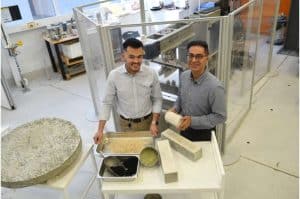

An international research group is building a case for more sustainable concrete by replacing synthetic reinforcement materials with natural fibers and materials from difference waste streams.

The latest Flinders University-led study, with experts from the US and Turkey, demonstrates how geopolymers reinforced with renewable natural fibers and made with industrial by-products and waste-based sands from lead smelting or glass-making can match the strength, durability and drying shrinkage qualities of those containing natural sand, which in turn consumes more raw resources and generates extra emissions in its processing.

Conventional concrete is the most widely used construction material, with 25 billion tons used every year. It consumes about 30% of non-renewable natural resources, emitting about 8% of atmospheric greenhouse gases and comprising up to 50% of landfill.

Lead researcher, Flinders University civil and structural engineering researcher Dr. Aliakbar Gholampour, says the promising findings have significant potential for the use of natural fibers in the development of structural-grade construction materials, in which binder and aggregate are replaced by industrial by-products and waste-based materials.

Test results showed that geopolymers using waste glass sand exhibit superior strength and lower water absorption than those containing natural river sand—while lead smelter slag (LSS)-based geopolymers have lower drying shrinkage compared to geopolymers prepared with natural river sand.

Natural fibers such as ramie, sisal, hemp, coir, jute and bamboo were also incorporated in testing experiments.

The geopolymers containing 1% ramie, hemp and bamboo fiber—and 2% ramie fiber—exhibit higher compressive and tensile strength and a lower drying shrinkage than unreinforced geopolymers, while those containing 1% ramie fiber have the highest strength and lowest drying shrinkage.

The new Australian-led study, published in Construction and Building Materials, adds to global efforts tackling the environmental impact of producing conventional building materials and waste-to-landfill volumes.

“With concrete, we can not only recycle huge volumes of industrial by-products and waste materials, including concrete aggregates, to improve the mechanical and durability properties of concrete, but also use alternative eco-friendly natural fibers which otherwise would not be used constructively,” says Dr. Gholampour.

“This research will also look to design mixes of recycled coarse aggregates and other types of cellulosic fibers including water paper, for different construction and building applications. We also plan to investigate their application in construction 3D printing for the future.”

October 10, 2022 By Editor

UN aviation agency members reached an agreement Friday to try to achieve by 2050 net-zero carbon emissions in air travel—often criticized for its outsized role in climate change.

The assembly, which brought together representatives from 193 nations at the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Montreal headquarters, reached a “historic agreement on a collective long-term aspirational goal (LTAG) of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050!” the UN agency said in a Twitter message.

It added that it “continues to advocate for much more ambition and investment by states to ensure aviation is fully decarbonized by 2050 or earlier.”

“It’s an excellent result,” a diplomatic source told AFP, revealing that that only four countries—including China, the main thrust of global growth in air travel—”had expressed reservations.”

The air transportation industry has faced growing pressure to deal with its outsized role in the climate crisis.

Currently responsible for 2.5 percent to three percent of global CO2 emissions, the sector’s switch to renewable fuels is proving difficult, even if the aeronautics industry and energy companies are seeking progress.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) said airlines were “strongly encouraged” by the adoption of the climate goal, coming one year after the organization endorsed the same position at its own general meeting.

IATA director general Willie Walsh said now “we expect much stronger policy initiatives in key areas of decarbonization such as incentivizing the production capacity of sustainable aviation fuels.”

According to airlines, it will require investments of $1.5 billion between 2021 and 2050 to decarbonize aviation.

“The global aviation community welcomes this landmark agreement,” said Luis Felipe de Oliveira, the head of Airports Council International, which represents 1,950 airports in 185 countries.

“This is a watershed moment in the effort to decarbonize the aviation sector with both governments and industry now heading in the same direction, with a common policy framework,” he said in a statement.

Deal is non-binding

The agreement, however, was far from satisfying for some non-governmental groups expressing regret it didn’t go far enough and was not legally binding.

Planes attract particularly sharp criticism because only about 11 percent of the world’s population fly each year, according to a widely quoted 2018 study by Nordic researchers.

In addition, 50 percent of airline emissions come from the one percent of travelers who fly the most, it found.

“This is not the aviation’s Paris agreement moment. Let’s not pretend that a non-binding goal will get aviation down to zero,” said Jo Dardenne of NGO Transport & Environment.

She also expressed disappointment over tweaks considered by delegates to the sector’s carbon offsetting and reduction scheme, known as CORSIA.

During the 10-day meeting, Russia had also sought but failed to get enough votes to be re-elected to the UN organization’s governing council, which is responsible for ensuring compliance with aviation rules.

Russia was accused of breaking international rules by registering hundreds of leased planes at home rather than returning them, as required by sanctions imposed after its invasion of Ukraine in February.

The ICAO general meeting was the first since the start of the pandemic, which had brought the airline industry to its knees: in 2021 the number of airline passengers was only half the 4.5 billion in 2019, marking a small rebound from the 60 percent year-over-year drop in 2020.

The sector hopes in 2022 to see to 83 percent of its customer levels from three years ago and to become profitable again worldwide next year.

October 9, 2022 By Editor

Engineers from UNSW Sydney have successfully converted a diesel engine to run as a hydrogen-diesel hybrid engine—reducing CO2 emissions by more than 85% in the process.

The team, led by Professor Shawn Kook from the School of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, spent around 18 months developing the hydrogen-diesel direct injection dual-fuel system that means existing diesel engines can run using 90% hydrogen as fuel.

The researchers say that any diesel engine used in trucks and power equipment in the transportation, agriculture and mining industries could ultimately be retrofitted to the new hybrid system in just a couple of months.

Green hydrogen, which is produced using clean renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, is much more environmentally friendly than diesel.

And in a paper published in the International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Prof. Kook’s team show that using their patented hydrogen injection system reduces CO2 emissions to just 90 g/kWh—85.9% below the amount produced by the diesel powered engine.

“This new technology significantly reduces CO2 emissions from existing diesel engines, so it could play a big part in making our carbon footprint much smaller, especially in Australia with all our mining, agriculture and other heavy industries where diesel engines are widely used,” says Prof. Kook.

“We have shown that we can take those existing diesel engines and convert them into cleaner engines that burn hydrogen fuel.

“Being able to retrofit diesel engines that are already out there is much quicker than waiting for the development of completely new fuel cell systems that might not be commercially available at a larger scale for at least a decade.

“With the problem of carbon emissions and climate change, we need some more immediate solutions to deal with the issue of these many diesel engines currently in use.”

High-pressure hydrogen direct injection

The UNSW team’s solution to the problem maintains the original diesel injection into the engine, but adds a hydrogen fuel injection directly into the cylinder.

The collaborative research, performed with Dr. Shaun Chan and Professor Evatt Hawkes, found that specifically timed hydrogen direct injection controls the mixture condition inside the cylinder of the engine, which resolves harmful nitrogen oxide emissions that have been a major hurdle for commercialisation of hydrogen engines.

“If you just put hydrogen into the engine and let it all mix together you will get a lot of nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, which is a significant cause of air pollution and acid rain,” Prof. Kook says.

“But we have shown in our system if you make it stratified—that is in some areas there is more hydrogen and in others there is less hydrogen—then we can reduce the NOx emissions below that of a purely diesel engine.”

Importantly, the new Hydrogen-Diesel Direct Injection Dual-Fuel System does not require extremely high purity hydrogen which must be used in alternative hydrogen fuel cell systems and is more expensive to produce.

And compared to existing diesel engines, an efficiency improvement of more than 26% has been shown in the diesel-hydrogen hybrid.

That improved efficiency is achieved by independent control of hydrogen direct injection timing, as well as diesel injection timing, enabling full control of combustion modes—premixed or mixing-controlled hydrogen combustion.

The research team hope to be able to commercialize the new system in the next 12 to 24 months and are keen to consult with prospective investors.

They say the most immediate potential use for the new technology is in industrial locations where permanent hydrogen fuel supply lines are already in place.

That includes mining sites, where studies have shown that about 30% of greenhouse-gas emissions are caused by the use of diesel engines, largely in mining vehicles and power generators.

And the Australian market for diesel-only power generators is currently estimated to be worth around $765 million.

“At mining sites, where hydrogen is piped in, we can convert the existing diesel engines that are used to generate power,” says Prof. Kook.

“In terms of applications where the hydrogen fuel would need to be stored and moved around, for example in a truck engine that currently runs purely on diesel, then we would also need to implement a hydrogen storage system to be integrated into our injection system.

“I do think the general technology with regards to mobile hydrogen storage needs to be developed further because at the moment that is quite a challenge.”