News and Information

November 7, 2022 By Editor

November 6, 2022 By Editor

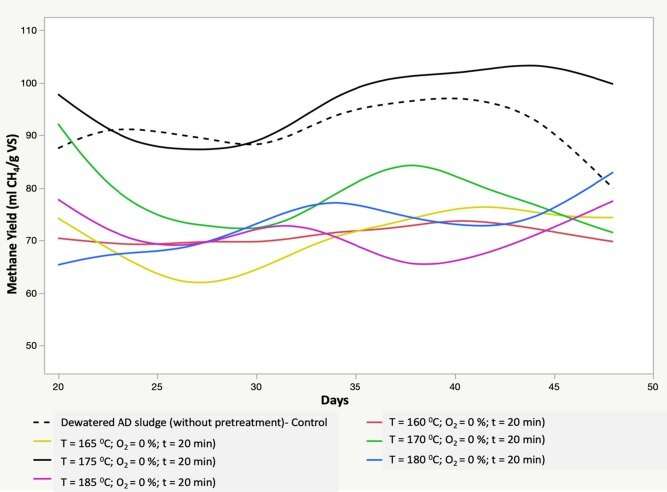

As climate change intensifies summer heat, demand is growing for technologies to cool buildings. Now, researchers report in ACS Energy Letters that they have used advanced computing technology and artificial intelligence to design a transparent window coating that could lower the temperature inside buildings, without expending a single watt of energy.

Studies have estimated that cooling accounts for about 15% of global energy consumption. That demand could be lowered with a window coating that could block the sun’s ultraviolet and near-infrared light—the parts of the solar spectrum that typically pass through glass to heat an enclosed room. Energy use could be reduced even further if the coating radiates heat from the window’s surface at a wavelength that passes through the atmosphere into outer space. However, it’s difficult to design materials that can meet these criteria simultaneously and can also transmit visible light, meaning they don’t interfere with the view. Eungkyu Lee, Tengfei Luo and colleagues set out to design a “transparent radiative cooler” (TRC) that could do just that.

The team constructed computer models of TRCs consisting of alternating thin layers of common materials like silicon dioxide, silicon nitride, aluminum oxide or titanium dioxide on a glass base, topped with a film of polydimethylsiloxane. They optimized the type, order and combination of layers using an iterative approach guided by machine learning and quantum computing, which stores data using subatomic particles. This computing method carries out optimization faster and better than conventional computers because it can efficiently test all possible combinations in a fraction of a second. This produced a coating design that, when fabricated, beat the performance of conventionally designed TRCs in addition to one of the best commercial heat-reduction glasses on the market.

In hot, dry cities, the researchers say, the optimized TRC could potentially reduce cooling energy consumption by 31% compared with conventional windows. They note their findings could be applied to other applications, since TRCs could also be used on car and truck windows. In addition, the group’s quantum computing-enabled optimization technique could be used to design other types of composite materials.

November 5, 2022 By Editor

Tapping the potential of geothermal energy could offer a way to repurpose inactive oil and gas wells, according to a University of Alberta experiment looking at the economic feasibility of heating drinking water for cattle.

Now published in Renewable Energy, the case study modeled the economic pros and cons of retrofitting disused wells on a large Alberta ranch to geothermally heat wintertime water for 2,000 cattle.

Though the idea ultimately came up dry financially for the rancher, the project yielded some useful information for future repurposing of orphan wells to harness thermal energy in the Earth’s crust, says Daniel Schiffner, who led the research.

“We’ve provided a good first step to take—a template for estimating the cost of converting a well and a way to predict the heat energy you can get for that well.”

With more than 450,000 inactive petroleum wells scattered across Alberta, finding economically feasible ways to reuse their infrastructure could ease the financial burden on taxpayers, adds Schiffner, who conducted the research as part of his master’s in science in risk and community resilience in the Faculty of Agricultural, Life & Environmental Sciences.

“If industry is unable or unwilling to reclaim a well, ultimately it falls upon the government to do so, so retrofitting presents an opportunity for other uses. We can benefit from turning some of them from a liability into an asset, and at the same time offset carbon emissions.”

The study’s findings help lay the planning groundwork for projects in particular areas, Schiffner suggests.

“I could see applications, for example, when talking about food insecurity in northern communities. If there’s a nearby well, they may be able to build a greenhouse and heat it with geothermal energy that’s right there.”

Similarly, farmers could operate greenhouses near inactive wells on land left idle after harvest, providing an additional income source, he adds.

“We could have some really interesting regional projects, and at the same time, make a small contribution to addressing the energy crisis.”

The case study, based in the lab of associate professor Lianne Lefsrud, focused on finding out the costs, benefits and power ratios of retrofitting inactive wells scattered around the ranch.

The researchers’ assessment estimated the geothermal power potential of some of the wells, along with all costs and revenues expected over a 25-year lifespan.

With a projection of $865,030 of expenses and just $19,255 of benefits, the researchers determined that a retrofit wouldn’t be economically feasible in this case. An expected reduction in livestock feed costs of just over $1,500 per year was too small to justify significant capital spending.

But the exercise did reveal factors that would make well retrofits more financially practical, including choosing wells that were classified as “suspended” rather than abandoned. The study estimated that retrofitting an abandoned well would cost up to $50,000 more, due to the extra time and materials needed to unseal it.

The researchers also found that reliable estimates of both the well retrofit costs and thermal power potential can be based on two factors: well location and vertical depth.

“Out of hundreds of thousands of wells, this helps quickly find and initially evaluate target areas that could be of interest,” says Schiffner.

Along with that, the study showed that the economic case for retrofitting is stronger if the well is located close to its intended use.

“Once you get that geothermal heat to the surface, it wants to dissipate, so the farther you have to transport that hot liquid, the cooler and less effective it’s going to get and the more you have to spend to transfer it.”

Besides benefiting the environment, the long lifespan of a geothermal energy source tends to outweigh the initial cost of retrofitting a well. This makes the economics of such a project more attractive to private industry, the study suggests.

“That might be an incentive that lets the government transfer the responsibility for some of these orphaned wells,” Schiffner notes.

November 4, 2022 By Editor

Heatwaves in numerous countries during 2022 sent all-time temperature records tumbling. On the day before the UK endured a shaded air temperature of 40°C for the first time ever, the Met Office issued its first ever red alert for extreme heat, which meant that people needed to take extra care to keep cool and avoid heat stroke.

In countries like the US and Japan, that might mean staying indoors and cranking up the air conditioning. But air conditioners are still relatively rare in many European countries, including the UK. Should increasingly brutal summer heat—and uncomfortably warm autumns—compel people to install them?

Actually, reasonable comfort can usually be maintained much more efficiently in a climate strongly influenced by the ocean, like the UK, with measures that use hardly any energy at all. These work to keep heat out, keep fresh air flowing and take advantage of the body’s natural ability to cool itself with evaporation.

Anyone considering an air conditioner should beware of ballooning energy bills. The compressors contained within consume sudden bursts of power. In places where air conditioning is common, the surge in demand during heatwaves can overwhelm local power networks. Blackouts result unless the increased electricity demand is met by backup generators, often gas turbines which can be fired up quickly.

All air conditioners compress refrigerant vapors such as hydrochlorofluorocarbons which are greenhouse gases thousands of times more powerful than carbon dioxide if they leak into the atmosphere.

It would be much better for the climate, household finances and the wider economy if buildings were insulated with windows designed to capture sunshine in winter and external shades to keep it out in summer. This is known as passive cooling because no energy is needed to keep the temperature lower.

Another alternative, especially if your building doesn’t have openable windows, is to use a mechanical ventilation system. These use fans to extract heat and indoor air pollution through ducts and sweep fresh air through rooms.

Any air conditioner you install will probably recirculate cooled indoor air rather than fresh air. Meanwhile, because mechanical ventilation systems channel cool air from outside and purge hot air, they can reduce temperatures in every nook and cranny for a fraction of the electricity that air-conditioning uses to constantly treat indoor air.

On days when the temperature is typically hotter outside the building than inside, ventilators can be used in the early morning when they can draw fresh air in at its coolest. If damp filters are installed in the ductwork, ventilation systems can cool a house further with no additional energy use.

From summer 2023, building regulations will require new housing in England to adopt passive or low-energy cooling features such as mechanical ventilation. Where high temperatures linger late at night (think large urban areas like central London and Manchester) housing developers will need to provide either external shutters, window glazing that restricts the sun’s heat but admits light, or awnings over south-facing windows.

Newer buildings are more prone to overheating because they tend to be made from lighter materials that heat up quickly. These dwellings are usually better insulated too, which can serve to trap the heat. Equipping them in this way can reduce the need for air-conditioning.

The London Assembly is mulling ways to adapt existing homes to extreme weather like heatwaves. The use of white-colored roofing materials or paints to reflect more of the sun’s energy is one of the methods being considered.

So-called “cool roofs” reflect visible rays of sunshine and radiate out invisible infrared heat from white surfaces, a trick deployed beautifully in a lot of traditional Greek architecture. Conventional insulation resists heat coming in but can also trap it indoors. Cool roofs allow heat to rise in your attic and escape from your roof to the sky.

When air conditioning may be necessary

People and horses are unique among mammals in our ability to regulate body temperature by secreting slightly salty water from millions of sweat pores in the skin. We can thrive in hot climates if we drink sufficient water—as long as our sweat continually evaporates in a breeze.

But at a certain threshold, sweat stops evaporating and accumulates. Humans cannot tolerate a wet-bulb temperature over 35°C (95°F) for long. Wet-bulb is the temperature of an object soaked in water as it is cooled by evaporation. This measure indicates the minimum temperature your skin can reach through sweating, while your core body temperature will be higher.

Whether a space is safe to occupy, and how much rest and rehydration is recommended, can be assessed by a combination of dry- and wet-bulb temperatures as well as exposure to the sun, producing a measure known as the wet bulb globe temperature. This takes into account the limits of sweating to cool you down during high humidity, as well as heat exposure from direct sunlight and that radiated from nearby surfaces like concrete.

A high wet bulb globe temperature is much more important in deciding whether air conditioning is needed than the dry-bulb temperature that weather forecasts report. My research identified where air-conditioning is a necessity: essentially, when there are ten days per year where the wet bulb globe temperature exceeds 29°C (85°F).

I showed that this is a reasonable guide for situations where air-conditioned shelters ought to be opened to the public. Nowhere in the UK has the Met Office (yet) measured so many stressful days in one year that air-conditioning is generally recommended using this guide.

But there are sun-drenched streets flanked by buildings on both sides (known as urban canyons) where weather stations are not installed, and the inside of badly designed buildings that become overheated. In such places, you might need to escape to an air-conditioned shelter or find sanctuary in a wooded park.

November 3, 2022 By Editor

November 2, 2022 By Editor

Two Aston University researchers have produced high-quality biodiesel after “feeding” and growing microalgae on leftover coffee grounds.

Dr. Vesna Najdanovic senior lecturer in chemical engineering and Dr. Jiawei Wang were part of a team that grew algae which was then processed into fuel.

In just the UK, approximately 98 million cups of coffee are drunk each day, contributing to a massive amount of spent coffee grounds which are processed as general waste, often ending up in landfill or incineration.

However the researchers found that spent coffee grounds provide both nutrients to feed, and a structure on which the microalgae (Chlorella vulgaris sp.) can grow.

As a result, they were able to extract enhanced biodiesel that produces minimal emissions and good engine performance, and meets US and European specifications.

The study appears in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews.

Until now, algae has been grown on materials such as polyurethane foam and nylon that don’t provide any nutrients. However, the researchers found that microalgal cells can grow on the leftover coffee without needing other external nutrients.

They also found that exposing the algae to light for 20 hours a day, and dark for just four hours days created the best quality biodiesel.

Dr. Najdanovic says that “this is a breakthrough in the microalgal cultivation system.”

“Biodiesel from microalgae attached to spent coffee grounds could be an ideal choice for new feedstock commercialization, avoiding competition with food crops.”

“Furthermore, using this new feedstock could decrease the cutting down of palm trees to extract oil to produce biofuel.”

“In southeast Asia this has led to continuous deforestation and increased greenhouse gas emissions.”