New method addresses problem with perovskite solar cells

News and Information

December 25, 2022 By Editor

December 24, 2022 By Editor

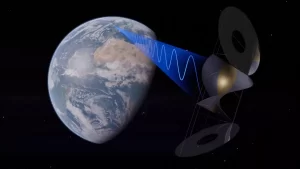

Beaming solar power from space used to be considered science fiction. But in recent years, space agencies from all over the world have launched studies looking at the feasibility of constructing orbiting power plants for real.

Such projects would be challenging to pull off, the stakeholders agree, but as the world’s attempts to curb climate change continue to fail, such moonshot endeavors may become necessary.

According to the United Nations’ Panel on Climate Change(opens in new tab), the world is currently on track to warm by 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit (2.5 degrees Celsius) by the end of the century. That is 1.8 degrees F (1 degree C) above the threshold considered safe by the international climate science community to avoid disastrous climate change consequences.

In fact, to limit the warming to anywhere near that threshold, the world’s economies would have to cut down their greenhouse gas emissions by 45% by 2030. That would mean phasing out a lot of fossil-fuel-guzzling technology in a very short period of time.

For example, the United Kingdom would need at least 30 to 40 gigawatts of new on-demand sustainable power generation to get rid of all fossil fuel power generation (according to a 2019 statement(opens in new tab)). That’s the equivalent of building over 30 new nuclear power plant blocks.

Solar power plants in space, exposed to constant sunshine with no clouds or air limiting the efficiency of their photovoltaic arrays, could have a place in this future emissions-free infrastructure. But these structures, beaming energy to Earth in the form of microwaves, would be quite difficult to build and maintain.

Here are the main pros and cons of this technology.

Ian Cash is a British engineer, whose CASSIOPeiA Solar Power Satellite concept has been adopted by a U.K. government-backed space energy initiative as a starting point for a potential future space-based solar power plant demonstrator. A staunch advocate of the technology, Cash thinks that developing and building a solar farm in space presents fewer challenges than cracking nuclear fusion.

When it comes to space-based solar power, “there is no science to solve,” Cash told Space.com. “We have it all worked out pretty much since the 1970s, when NASA with the U.S. Department of Energy conducted a very large-scale study. We’ve proven the physics behind this ever since we first launched a communication satellite into geostationary orbit. You’ve got solar wings, which face the sun. And you have the body of the satellite, either with a parabolic dish or a phased array antenna, which faces the Earth. All the principles are the same; you’re converting solar energy to electricity, converting it to microwaves and beaming it to Earth. The only thing that’s different is the scale of the apertures.”

Andrew Wilson, a researcher at the Advanced Space Concepts Lab at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland, who led a study looking into the feasibility of space-based solar power, agrees: “I don’t think there’s technology that needs to be developed as opposed to just advancing through the technology readiness levels,” Wilson told Space.com. “There’s nothing really that needs to be invented.”

However, as detailed later in this piece, the required “technology advancing” is rather considerable.

Building solar power plants in space certainly isn’t an easy task, but it seems to have advantages — at least for some countries. The technology’s proponents claim that a solar-power plant in Earth’s orbit would produce 13 times more power than an equivalent installation located in the notoriously cloudy U.K.

Space-based solar power plants would easily produce gigawatts of power, matching the electricity output of nuclear power plants. In contrast, the U.K.’s largest solar power plant, Shotwick Solar Park(opens in new tab) in northern Wales, produces a meager 72.2 megawatts during peak insolation times. Only the world’s largest solar plants, sprawling installations in some of the sunniest countries, reach the gigawatt mark. For example, the Bhadla solar farm in India generates up to 2.7 gigawatts and covers 52 square miles (160 square kilometers) of land, which is more than double the size of Manhattan, according to the Ecoexperts.

Building a solar power plant in space would come with an enormous price tag. Once built, however, the plant would pay for itself much faster than any Earth-based renewable power generating technology, according to Wilson.

Space-based solar power doesn’t suffer from the main drawback plaguing most main renewable energy generation technologies. In space, the sun always shines. No clouds ever block the sun’s rays from reaching photovoltaic arrays. And if you choose the orbit wisely, you can even avoid the night. A solar power plant in space, unlike its equivalent on Earth, or an off-shore wind farm, would provide a constant amount of power 24/7 year-round. This power would feed Earth-based power grids at a steady rate without having operators worry about pesky blackouts or sudden overloads.

Space-based solar power proponents, however, don’t expect the heavenly electricity to push out more humble ground-based renewables. They think space-based solar power should replace power plants that are currently being used to cover energy needs when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow. In the U.K., this so-called dispatchable power comes mostly from oil and gas-fired power plants, the type of carbon-producing facilities that are adding to the world’s growing climate-change problem..

“The thing with space based solar power is that very high levels of power can be delivered, similar to nuclear power plants,” Wilson said. “Most other renewable energy options can’t provide such quantities at once. Without space-based solar power, we would probably be looking to build many more nuclear power stations, for sure.”

Of course, renewable power could be fed into giant batteries in times of surplus generation to be used at times of need. But energy storage technology of this scale is only slightly more solved then nuclear fusion.

Space-based solar power doesn’t suffer from the main drawback plaguing most main renewable energy generation technologies. In space, the sun always shines. No clouds ever block the sun’s rays from reaching photovoltaic arrays. And if you choose the orbit wisely, you can even avoid the night. A solar power plant in space, unlike its equivalent on Earth, or an off-shore wind farm, would provide a constant amount of power 24/7 year-round. This power would feed Earth-based power grids at a steady rate without having operators worry about pesky blackouts or sudden overloads.

Space-based solar power proponents, however, don’t expect the heavenly electricity to push out more humble ground-based renewables. They think space-based solar power should replace power plants that are currently being used to cover energy needs when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow. In the U.K., this so-called dispatchable power comes mostly from oil and gas-fired power plants, the type of carbon-producing facilities that are adding to the world’s growing climate-change problem..

“The thing with space based solar power is that very high levels of power can be delivered, similar to nuclear power plants,” Wilson said. “Most other renewable energy options can’t provide such quantities at once. Without space-based solar power, we would probably be looking to build many more nuclear power stations, for sure.”

Of course, renewable power could be fed into giant batteries in times of surplus generation to be used at times of need. But energy storage technology of this scale is only slightly more solved then nuclear fusion.

The apparent sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipelines in the Baltic Sea that shocked the world in September 2022 showed that, in the politically unstable world that we live in, relying on energy from abroad is rather unsafe.

Space-based solar power, proponents say, is more secure from international conflict than gas supplies from Russia — and more secure than traditional solar plants here on Earth as well.

“Some people say that if you strategically place solar panels in certain unpopulated regions in, for example, the Sahara desert, you could power all humanity’s energy needs,” said Wilson. “But the same thing that we have seen happen with Russia could then happen to our energy security if a war erupted in the Sahara region.”

Some opponents argue that a space-based solar power plant could be easily attacked by anti-satellite missiles. Cash, however, disagrees. Shooting down a platform in geostationary orbit, he says, is outside of the current capabilities of most states. On top of that, while disrupting undersea pipelines in a stealth way using submarines allows for plausible deniability, an adversary launching a missile to destroy a space-based solar plant of a rival would be easily identified.

“There certainly is a risk, but it’s no greater than hostile players wanting to attack nuclear power stations, gas pipelines or high voltage power line cables running between continents,” Cash said. “Many of these things can be attacked covertly, and the attacking nation can easily deny responsibility. But in space, any attack involves a launch that will surely be detected.”

Wilson added that, as any space-based solar power plant project will most likely be an international endeavor, the international nature provides an extra layer of protection against political upheavals.

Photovoltaic plants on the ground devour huge areas of land to harvest any reasonable amount of power. Wind farms in the landscape, too, are unmissable. The rectifying antennas (or rectennas) needed to receive microwave beams carrying solar power generated in space would too require a huge footprint. These rectennas will, however be far less obtrusive, claimed Cash, and allow for other uses of the land or sea on which they will be built.

“The rectennas will be a thin mesh construction; they’ll let sunlight through and will be almost invisible when viewed from a distance,” Cash said. “We envisage a future where we could have a rectenna raised up a few meters above ground via poles, and repurpose the land underneath for, say, robotic farming or even human farming, as the land will be underneath a microwave shield, so there will be no exposure to microwave radiation.”

In Airbus’ idea of the future, solar power produced in space could contribute to cleaning up the hard-to-deal-with carbon footprint of aviation. Not that it would wean aircraft off fossil fuels entirely, but it could make a little dent in the amount of greenhouse gas the world’s aircraft discharge into Earth’s atmosphere.

“In the future, as we move toward hydrogen and battery-powered aircraft, we could use space-based solar power to extend the range of aircraft,” Coste said. “We could use it in takeoff assist, because the takeoff is the moment where you use most of the fuel. You could have a beam that provides energy during takeoff and later to also recharge the aircraft as they fly.”

The orbiting solar power plant will have to be enormous, and not just to collect enough sunlight to make itself worthwhile. The main driver for the enormous size is not the amount of power but the need to focus the microwaves that will carry the energy through Earth’s atmosphere into a reasonably sized beam that could be received on the ground by a reasonably sized rectenna. These focusing antennas, Cash said, would have to be 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) or more wide, simply because of the “physics you are dealing with.”

Compare this with the International Space Station, at 357 feet (108 meters) long the largest space structure constructed in orbit to date. Space based solar power proponents all agree that how exactly such plants could be put together is still a question.

Cash says that his CASSIOPeiA concept would work also with multiple smaller plants in some types of lower Earth orbits. Having a plant closer to Earth would allow for the antenna to have a smaller size, possibly reducing the scale to one-tenth of what would be needed in geostationary orbit. On the other hand, a plant closer to Earth would be an easier target for anti-satellite missiles and might also annoy astronomers, as it would be too visible from the ground.

In every case, building a space-based solar power plant would require hundreds of rocket launches (which would pollute the atmosphere depending on what type of rocket would be used), and advanced robotics systems capable of putting all the constituent modules together in space.

This robotic construction is probably the biggest stumbling block to making this science fiction vision a reality, Cash said.

“If we can demonstrate that we can assemble smaller CASSIOPeiA satellites, 12 meters [40 feet] in diameter, using robots, then we can gradually expand to 100-meter [330 feet], 1 kilometer [0.6 miles] or 2 kilometer [1.2 miles] scales,” Cash said. “We would just need to apply more robots working in parallel. But certainly, it’s one of the key challenges.”

Airbus, which recently conducted a small-scale demonstration converting electricity generated by photovoltaic panels into microwaves and beaming it wirelessly to a receiving station across a 118-foot (36 m) distance, says that one of the biggest obstacles for feasible space-based solar power is the efficiency of the conversion process.

Microwaves slide through Earth’s atmosphere almost undisturbed, losing barely 5% of their energy during their journey from geostationary orbit, according to Airbus’ calculations. Huge amounts of energy, however, are lost already at the plant and then at the rectenna when the electricity produced by the photovoltaic panels is turned into microwaves and then back to electricity.

“The system we used in our demonstration had end-to-end efficiency of about 5%,” said Coste. “That’s not something that would be operationally viable, even though the sunlight is free. For a space-based solar plant to make sense, the efficiency would have to be around at least 20%.”

Some worry that microwave beams in space could be turned into weapons of mass destruction and used by evil actors to fry humans on the ground with invisible radiation.

Coste admitted that if someone wanted to develop such a weapon, they possibly could. The microwave beams carrying space-based solar power, however, would be engineered from the onset to be safe.

How dangerous the beam is to human health, he said, depends on the density of the power it carries, and that could be limited by design.

“You could design the beam to be so safe that you could take a nap in it with your child and not be affected,” said Coste. “That would be at a power density level of about 10 watts per square meter. But that will require an extremely large area to collect [the energy], so we would want to have a narrower beam with higher density and some safety system around it.”

The company, he says, is looking into methods of “traffic management around the beam,” using radars and lasers to look for objects in the beam’s vicinity to stop the energy flow in case of a safety risk.

“We can engineer a system that is designed to only be pointed at a receiver and would not ever work if it pointed anywhere else,” said Coste. “We work on this concept with some big energy companies in Europe, and they don’t see it as too much of an issue, as they are used to dealing with safety problems around high-voltage power lines or gas pipelines.”

The vast orbiting structure of flat interweaving photovoltaic panels would be constantly battered by micrometeorites, running a risk of not only sustaining substantial damage during operations, but also of generating huge amounts of space debris in the process.

The James Webb Space Telescope, with its 21.6-foot-wide (6.5 m) mirror, received quite a few significant hits early in its operations, prompting its ground control team to adjust observing plans to avoid gazing in the direction where most of the rocks come from.

The engineers designing a possible future space-based solar power plant would certainly have to build their structure with this constant micrometeoroid influx in mind.

“For the lifecycle of the station, you have to design it in a way that it can be maintained and repaired continuously,” said Coste. “Because it’s such a large structure, you will have some defects in some panels. The ideal design of the antenna will be modular so that you could replace tiles and panels.”

Cash added that, by making the panels from the thinnest possible material, engineers can almost eliminate the generation of debris from the stricken panels.

“If we make it from some type of polymer materials, then things like micrometeorites would just punch a hole straight through,” Cash said. “We would hope that we can reduce the risk of generating debris but also the effects on the plant. If we build each of the modules to be independent of other modules, then all that happens is that a strike takes out a few elements.”

But what about the end of life? What would happen with faulty modules that had to be replaced? And what about the whole thing once it reaches the end of its life, perhaps after a few decades of power generation? Will an object 1 mile (1.6 km) across be left in geostationary orbit to slowly decay?

Wilson envisions a more sophisticated disposal procedure, which assumes that, by the time we may have space-based solar power plants, we are most likely going to see quite a bit of permanent infrastructure on the moon. Space tugs that don’t exist yet could then move the aged plant to the moon, where its materials could be recycled and repurposed for another use.

“One of the ideas for the future utilization of the moon is to use it for space launches into deeper space,” said Wilson. “We could also have some kind of recycling center there to process some of the material.”

Some astronomers are concerned about the impact of such giant orbiting structures on the night sky. SpaceX’s Starlink constellation has been provoking backlash from the astronomy community ever since the company’s first satellite batches spread across the sky in the form of luminous trains.

The International Astronomical Union decried Starlink as a worse threat to astronomy than urban light pollution, with large-scale survey telescopes scanning vast swaths of the sky especially affected.

But Coste thinks that a plant in geostationary orbit, 22,000 miles away from Earth, would be barely noticable.

“From Earth, you would perceive it like a single star,” he said. “The only part of the plant that will be facing Earth is the antenna, and that doesn’t need to be light-reflecting. We could probably do something to the system to reduce the amount of light that is coming [to Earth]. I don’t think it is as big a problem as the megaconstellations.”

Cash agrees: “The whole concept [of a space-based solar power plant] is to gather and absorb as much sunlight as possible. We maintain this constant attitude, always sun-facing. And any parts which aren’t absorbing that sunlight, we can arrange them in principle to deflect the sunlight away from Earth.”

So what do you think? Should space-based solar power become a thing? Airbus appears serious about its plans, expecting to launch a small-scale demonstrator with an aerial platform in the next two years. A small-scale energy-beaming satellite might be in orbit by the end of this decade.

“We see no showstopper,” concluded Coste.

December 23, 2022 By Editor

December 22, 2022 By Editor

Almost one in three Australian households have solar panels on their roofs. Most are motivated by rising electricity prices and environmental concerns.

Households are paid a so-called feed-in tariff for surplus energy they export to the grid. While customers would love to get paid for every bit of energy they’re able to export to the wider grid, operators have imposed a fixed or “static” limit on how much energy each household can export. This helps keep network voltages—or electric pressure—within a safe range.

The limits are needed because of uncertainty about the impacts on the network of fluctuations in households’ energy use and exports.

The network is connected to households via “low voltage” transformers that reduce the voltage to a level customers can use. The uncertainty arises because operators can see what’s happening at each transformer, but not what’s happening in each household.

We are working on a data-monitoring project to enable network operators to see household voltage and current data in real time. The idea is to enable them to manage network voltage fluctuations more precisely.

This could allow households to safely export more solar, depending on local network conditions. People would arguably receive more money while speeding up the transition to zero-emissions electricity by providing more renewable energy to the network.

The electricity network was originally set up for “bulk” generation from centralized power stations. The flow was in one direction from coal, gas or hydroelectric stations to energy users, including households.

However, economic forces and aging systems mean many of these power stations are being rapidly retired. They’re being replaced, in part, by so-called “distributed energy resources.” These resources include rooftop solar, household or community batteries, and electric vehicles.

The household export limit to the network is usually around 5 kilowatts (kW), regardless of time of day or what households are generating or consuming. But, because of the falling cost of solar, 10kW residential systems (capable of producing twice the export limit) are increasingly common.

The Australian grid operator, AEMO, envisages distributed solar generation will make up 69GW of network capacity by 2050, compared to around 21GW now.

Integrating this energy generation is a big challenge for the energy market, transmission and distribution network operators.

The Australian Standard for household voltage has “allowable” and “preferred” operating zones around 230 volts. Keeping the voltage within these zones is better for energy efficiency and appliance life.

But when energy flow is “two-way” and unpredictable, both to and from houses, it becomes more challenging to keep the voltage within these zones. When lights flicker or appliances are damaged, that’s a sign the voltage is outside these safe limits.

How much household data do operators need?

If the operators could see household voltage and current data in real time, they might be able to set “dynamic” limits on households for the import and export of energy. That means limits are allowed to fluctuate depending on local network conditions, instead of being static. Households might then be able export more energy overall than they do now.

A long-term project of the Australian Renewable Energy Agency, Project SHIELD, aims to answer a key question here. That is, how much data do operators need to allow this flexibility, while still safely co-ordinating energy flows to and from the grid?

The project involves The University of Queensland, network operators and the private sector. A project partner, Luceo Energy (an offshoot of a company that formerly employed one of the authors), working with Energex, Ergon and Essential Energy, has rolled out 20,000 devices in households across Queensland that collect their energy data at one-minute intervals.

Smart meters installed in Victoria typically record energy data every 30 minutes. The new devices measure multiple electricity parameters, such as voltage and current, every minute.

This creates extraordinary amounts of data, which can be used in electricity studies and simulations. It also creates storage and analysis challenges.

The data collected are used to answer “what if?” questions. If an operator had perfect knowledge of conditions at every house attached to a transformer, they could create a safe dynamic limit. But would it still be safe if they could see the data for only 50%, or even 20%, of houses?

World-first simulation systems developed by Queensland company GridQube enable the operators to answer such questions. Data collected by the devices provide a key input.

Several representative locations and time periods have been chosen to see how network visibility can affect the envelope. The local network is simulated using a “power flow” with different network parameters, such as voltage. Then the key questions around safe limits can be answered.

Benefits for both consumers and operators

Of course, this is only one level of the electricity network. We still need to build considerable amounts of high-voltage transmission to integrate increasing distributed energy resources. This will help provide a reliable and secure power supply.

The data generated by Project SHIELD will inform electricity modelers and data scientists about what is happening at the household level (both electricity usage and solar generation). It can improve forecasting and modeling as data on this scale have not been previously available.

As the roll-out of devices and gathering of data continue at speed, operators can start to relax the limits on household solar energy exports. Greater visibility of local networks offers clear benefits for both consumers and operators.

December 21, 2022 By Editor

Hydrogen has a part to play in the U.K.’s shift to a net-zero economy but its role will likely be restricted to certain sectors, according to a report from an influential committee of U.K. lawmakers.

The House of Commons Science and Technology Committee concluded that although hydrogen possessed “several attractive features, most of the evidence we have received was clear that with current technologies, it does not represent a panacea.”

“As the UK looks to transition to a Net Zero economy, hydrogen will likely have specific but limited roles to play across a variety of sectors to decarbonise where other technologies — such as electrification and heat pumps — are not possible, practical, or economic,” the report, which was published Monday, said.

Described by the International Energy Agency as a “versatile energy carrier,” hydrogen has a diverse range of applications and can be deployed in a wide range of industries.

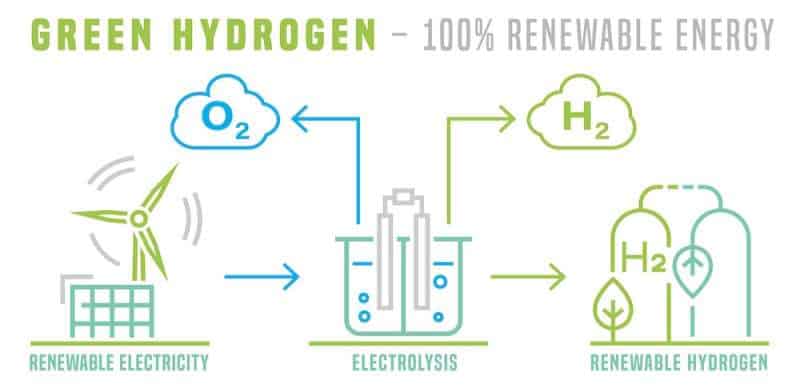

One method of producing hydrogen uses electrolysis, a process through which an electric current splits water into oxygen and hydrogen.

Some call the resulting hydrogen “green” or “renewable” if the electricity used in the electrolysis process comes from a renewable source such as wind or solar. The vast majority of hydrogen generation today is based on fossil fuels.

Monday’s report sought to temper expectations about the role hydrogen could play in slashing emissions and the transition to a net-zero economy.

“To make a large contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the UK, the production of hydrogen requires significant advances in the economic deployment of CCUS [carbon capture, utilization and storage] and/or the development of a renewable-to-hydrogen capacity,” it said.

“The timing of these is uncertain, and it would be unwise to assume that hydrogen can make a very large contribution to reducing UK greenhouse gas emissions in the short- to medium-term.”

Committee chair Greg Clark said that there were “significant infrastructure challenges associated with converting our energy networks to use hydrogen and uncertainty about when low-carbon hydrogen can be produced at scale at an economical cost.”

“But there are important applications for hydrogen in particular industries so it can be, in the words of one witness to our inquiry, ‘a big niche’,” Clark added.

Industry group Hydrogen Europe did not immediately respond to a CNBC request for comment.

Over the past few years, major economies and businesses have looked to the emerging green hydrogen sector to decarbonize industries integral to modern life.

During a roundtable discussion at the COP27 climate change summit last month, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz described green hydrogen as “one of the most important technologies for a climate-neutral world.”

“Green hydrogen is the key to decarbonizing our economies, especially for hard-to-electrify sectors such as steel production, the chemical industry, heavy shipping and aviation,” Scholz added, before acknowledging that a significant amount of work was needed for the sector to mature.

“Of course, green hydrogen is still an infant industry, its production is currently too cost-intensive compared to fossil fuels,” he said. “There’s also a ‘chicken and egg’ dilemma of supply and demand where market actors block each other, waiting for the other to move.”

Also appearing on the panel was Christian Bruch, CEO of Siemens Energy. “Hydrogen will be indispensable for the decarbonization of … industry,” he said.

“The question is, for us now, how do we get there in a world which is still driven, in terms of business, by hydrocarbons,” he added. “So it requires an extra effort to make green hydrogen projects … work.”

December 20, 2022 By Editor

Renewable energy is an essential factor in Europe’s goal of becoming the first carbon-neutral continent. The climate crisis and the soaring price of natural gas have placed renewed emphasis on the need to transition to a low-carbon energy system.

Europe is on its way: of the 2,664 TWh of electricity produced in Europe in 2020, 34% was provided by renewable sources. But while renewable energy is abundant, you still need to build the infrastructure to capture it.

To meet Europe’s total energy demand with renewables alone would require a large number of infrastructure projects. Each of these would compete with other land uses, such as residential and industrial developments, agriculture and nature.

There is, however, a large empty space with ample amounts of renewable energy nearby: Africa’s Sahara desert. Could one giant solar array there replace Europe’s energy generation?

“If all the engineering, environmental and political challenges are fully addressed, then yes, sufficient energy can be generated in the Sahara using solar plants to cover a large fraction of the EU’s current electricity demand,” says Mahkamov, a professor of Mechanical and Construction Engineering at Northumbria University.

“Considering that the total area of the Sahara is estimated to be around 9.3 million km2, and that it has an average insolation of 263 W/m2, and taking into account the current level of development and efficiency of today’s solar power technologies, then yes, the Sahara desert does present a huge potential for generating similar quantities of electricity, although with seasonal fluctuations,” he explains.

But the devil’s in the detail.

Sun, sand and solar power

According to Mahkamov, before we can build a giant solar array in the Sahara, we must first research the long-term environmental and social impacts that covering such a vast area with photovoltaics would have.

Then, there’s the issue of installing a large, critical infrastructure in such a remote and oftentimes harsh environment. A Sahara solar installation would also likely face a number of maintenance problems related to the detrimental effect of ongoing sandstorms and the continuous movement of sand across the desert.

Furthermore, unlike the solar panels installed on a roof, solar megaplants have a range of unique requirements. “The conversion technologies must be diversified, and the deployment of a combination of different technologies is also needed to achieve robustness in energy production and full utilization of an intermittent solar irradiation spectrum,” adds Mahkamov.

Another issue that cannot be ignored is that building a mega solar installation in the Sahara would still leave Europe wholly dependent on foreign energy imports, and vulnerable to all the problems that come with such dependence.

The advantage of starting small

Mahkamov says the focus should be on expanding the solar infrastructure right here in Europe—a process that can start by installing solar plants in the vicinity of our own homes.

As part of the Innova MicroSolar project, a consortium led by Mahkamov developed a high-performance, cost-effective concentrating solar power system for small-scale, on-site electricity and heat generation. Instead of one giant array, imagine thousands of much smaller ones.

“The system has the potential to provide the highest energy savings in southern EU countries, covering all electricity demand in some,” he concludes. “When used in a single-family dwelling, it reduces CO2 emissions by 70 to 95% in southern locations, and about 30% on average in other countries.”