America Desperately Needs To Invest More In Battery Recycling

News and Information

October 16, 2022 By Editor

October 15, 2022 By Editor

Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer wasn’t happy. Ford Motor Co., a company whose very name is synonymous with Detroit, had just announced it had chosen two southern states, Tennessee and Kentucky, as sites for an $11 billion electric-vehicle project.

They had won Ford over by dangling huge incentives, and Whitmer knew Michigan needed to do more to compete. So she pleaded with lawmakers in a letter last October to put “more tools in our economic toolbox to attract private investment.” Two months later, they delivered, handing her a $1 billion fund for corporate subsidies. And a month after that, Whitmer dipped into the fund to net a giant deal from General Motors Co.: a $6.6 billion electric-truck factory and battery plant.

Michigan’s largesse — and Tennessee’s and Kentucky’s — was made possible in part by hundreds of billions in federal aid pumped into US states as part of President Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan. The money was meant to soften the blow of a pandemic-induced fiscal apocalypse that never happened. Instead, it’s left states flush with cash, supercharging competition to win the automotive jobs of the future and cushioning the bottom lines of companies like Ford, GM, and Panasonic Holdings Corp., a battery supplier to Tesla Inc.

There’s a risk that all the money sloshing around amid the EV development frenzy will fund boondoggles, like Foxconn Technology Group’s heavily subsidized television factory in Wisconsin that never materialized.

To counter that risk, state and local officials helping to fund this EV boom say they built in protections to keep taxpayers from getting fleeced. But the stakes are getting bigger: The cost per permanent job for some projects is now eight times the average seen less than a decade ago.

Ford’s Tennessee hub will cost about $414,000 for each direct job, Michigan is contributing $450,000 per GM job, while Georgia committed to forgo revenue that amounts to $212,000 per job to win megaprojects from Rivian Automotive Inc. and Hyundai Motor Co. in the past two years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The average per-job cost of economic incentives in the US was about $52,000 in 2015, measured in today’s dollars, according to a study by Tim Bartik, an economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

States have been competing to lure companies since at least the Great Depression. But the scale and the ferocity of it now — for EV plants, semiconductor factories and other megaprojects — are unprecedented.

“I have never seen the same kind of surge in subsidies all across the US all happening at the same time,” said Michael Farren, a senior researcher at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and a critic of corporate incentives. “It’s pretty clear that there’s an external motivating factor, and that is the American Rescue Plan relief funds.”

Companies that receive incentives saved an average of 30% on state and local taxes as of 2015, a rate that had tripled since 1990, according to the study by Bartik. The same study found incentives don’t correlate strongly with states’ current or past unemployment levels, or future economic growth.

To skeptics, of whom there are many in academia and policy circles, these subsidies are a poor use of state resources that could otherwise be earmarked to hospitals or schools. The incentives create a race-to-the-bottom effect where local governments furiously try to one-up each other on handouts that deliver unproven payoffs. There’s also a question as to whether EV and battery plants will employ as many people or pay as well as combustion-engine cars.

“States have justified huge subsidy packages for assembly plants in part to capture the more numerous upstream jobs, but those jobs are clearly going to shrink a great deal,” said Greg Leroy, the executive director of Good Jobs First, which has written a report on the subject.

The $350 billion that Congress set aside for states and municipalities in May 2021 is coinciding with a once-in-a-century transformation of the auto industry, as carmakers prepare to retire the combustion engine in favor of battery power. While there are strict limits on how local governments can use the Covid relief money, the aid helped free up cash for corporate incentives.

Financial disclosures vary by state, and some withhold data at the behest of a company or to stay competitive against other states. This makes the full picture of corporate incentives incomplete.

| Company | State | Investment | Subsidies | Jobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM | Michigan | $6.6 Bln | $1.8 Bln | 4,050 |

| Ford | Tennessee | $5.6 Bln | $2.4 Bln | 5,800 |

| Hyundai | Georgia | $5.5 Bln | $1.8 Bln | 8,100 |

| Rivian | Georgia | $5 Bln | $1.5 Bln | 7,500 |

What is known is that global carmakers and established battery manufacturers have announced plans to invest at least $50 billion into at least 10 states to build EV assembly and battery plants since the start of 2021, and states have made commitments totaling at least $10.8 billion to lure those investments, according to a tally of publicly disclosed incentives by Bloomberg and Good Jobs First. That figure almost certainly underestimates the actual number.

The electric-vehicle hub that Ford and battery partner SK Innovation Co. chose to locate in Tennessee is a good example of how the full cost of an incentive package typically isn’t made plain to the public.

Blue Oval City, a six-square-mile site an hour’s drive northeast of Memphis, will house an assembly plant making the new electric F-150 pickup and a battery plant that together promise to create 5,800 jobs. Construction will generate 33,000 temporary jobs; once completed, the twin plants and their suppliers will support 27,000 direct or indirect positions, and add $3.5 billion annually to Tennessee’s economy, state officials have said.

When the project was announced, state officials disclosed a $500 million cash grant to be approved by the legislature; local press reports later pegged the cost at $884 million.

In fact, contract documents obtained by Bloomberg show the value of the package is at least $2.4 billion, which includes tax breaks, donated land, infrastructure improvements and short-term wage subsidies from the federal government.

Even that figure is an undercount. It excludes an electricity subsidy provided by the Tennessee Valley Authority, the largest federal utility.

Tennessee officials said Bloomberg’s incentives calculation is “misleading” because some infrastructure investments were made years earlier, and some of the workforce training costs are estimates. They also argue that new property tax revenue, even at a reduced rate, is more than local governments would get without the project.

“Blue Oval City will be transformational for West Tennessee,” said Lindsey Tipton, a spokeswoman for the state’s economic development department. “For future projects, we will offer grant assistance, but at a much lower cost-per-job and more in line with a typical incentive package from our department.”

Ford said its decision was influenced by many factors beyond financial incentives.

“Public-private partnerships are essential for the United States to be a leader in the global transition to electric vehicles,” the company said in a statement.

Even states that have tried to move away from incentives have caved to the pressure to compete for jobs, said Dennis Cuneo, a former Toyota Motor Corp. executive and site consultant who has helped automakers pick locations.

“Incentives are like free agency in baseball — nobody likes it, but you’ve got to do it if you want to win,” he said.

Georgia, which has emerged as a big winner in the current investment surge, landed two $5 billion EV deals from Rivian and Hyundai that promise to create more than 15,000 jobs. The state offered incentives worth $3.3 billion to win the projects.

State economic commissioner Pat Wilson said Georgia competes by helping companies move fast with shovel-ready sites and limited red tape, rather than putting the most cash on the table. He called Bloomberg’s per-job incentives calculation “terribly misleading” because it includes tax breaks written into state law that aren’t discretionary.

“I view the incentives that we put on the table really as Georgia being part-investor in these projects,” Wilson said in an interview. “We know the payroll for those jobs and the benefits they provide are going to trickle out and benefit the health of communities and families all across the state.”

October 14, 2022 By Editor

THE CATHODE IS a marvel of molecular choreography. How much power a battery holds, and how long it lasts, depends on its lattice of metallic atoms—how well it can catch and release lithium ions. For decades, engineers have fiddled with designs that help this movement along. And they’ve gotten pretty good, if the electrical vehicles and phones of today are any barometer. But the cathode is also the place where things inside the battery typically go wrong. This immaculate structure, so artfully arranged, starts to lose its integrity. Ions run loose, or clog up. Just like that, your battery life goes kaput.

But even as the structure fails, the atoms inside of the cathode haven’t changed. This is why, in theory, it should be possible to reuse them. “A metal atom is a metal atom,” says Alan Nelson, senior vice president for battery materials at Redwood Materials, a company that specializes in recycling. “That element doesn’t know if it was previously in a battery or if it was in a mine.” This is potentially a good thing, because many of those atoms, including metals like cobalt and nickel, are in short supply and only found in major volumes in places where mining them entails major ecological and human costs. Today, Nelson’s company released the results of tests at Argonne National Lab comparing recycled materials to virgin ones. These suggest it’s true that an atom is an atom; the performance of the two materials was almost exactly the same.

Redwood is one of a number of companies trying to turn a supply of old batteries into materials for new ones. That’s low-hanging fruit, in the sense that it involves using up waste and could ease some of the pressure on new mines. But last year, the company, which originally sold its recycled raw materials to other suppliers, took the unusual step of announcing plans to produce its own cathode materials, and later selected a site outside of Reno, Nevada, where it would spend $3.5 billion over 10 years on a new plant. The company says it plans to produce enough cathode material (as well as copper anode foil) for 100 GWh worth of battery cells by 2025—roughly equivalent to what CATL, the dominant battery maker in China, produced last year.

That’s something of a departure for the US battery industry. Despite a flurry of manufacturing announcements, bolstered in part by infrastructure spending and the climate provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act, most have been focused on the steps closest to automakers and consumers, like assembling battery cells and packs. The US has meanwhile struggled to build up industries that lie deeper in the supply chain—from the mining that digs up key minerals such as lithium and cobalt to the extensive processing that turns them into components like the cathode. Most of that is done elsewhere. According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a group that studies the battery supply chain, China currently makes 78 percent of the world’s cathode materials, and that share is poised to grow to 90 percent by 2030, despite efforts in the US to invest in domestic battery supply chains.

One reason Chinese firms remain so dominant is that they have a closed loop of battery production, says Hans Eric Melin, founder of Circular Energy Storage, a consultancy that tracks battery recycling. Having battery cell production at home means it’s possible to break down scrap materials and quickly put the valuable metals back into production. The complex supply chain that refines the raw metals into that perfect crystalline cathode structure is also localized, centralizing expertise and reducing transportation costs.

Redwood is among the companies trying to pull the US manufacturing loop a little tighter. The tests, which were performed by independent researchers at Argonne National Lab, are an early step in a qualification process to reassure battery makers of the quality of these hand-me-down materials. The process begins by taking the battery apart and breaking its components down with heat and acids into metal sulfate compounds, composed of elements like cobalt, manganese, and nickel.

Once those metals have been separated, the next step is putting them together again. The design tested by the Argonne researchers is what’s known as NMC-811: 80 percent nickel, 10 percent manganese, and 10 percent cobalt. These nickel-rich cathodes have been prioritized by automakers like Tesla because they rely less on cobalt while retaining the driving range EV owners have come to expect from their new cars. The researchers took two sets of precursor materials—recycled metal sulfates provided by Redwood and sulfates made with raw material—and ran them through a series of steps that intimately mix the elements together and then layer in rows of lithium. The result is a cathode material that could be stuck into battery cells and run through a set of standard tests.

Those tests are meant to capture measures like capacity, cycle life, and rate capability, which relates to a battery’s power. The researchers found the two types of cathodes—recycled and virgin—to be nearly identical by these measures. (In some cases the recycled versions tested better, though the team cautioned that this couldn’t be tracked back to recycling.) “Honestly, it’s a pretty boring result,” says Jason Croy, a battery scientist at Argonne National Laboratory who led the research. But it wasn’t a given, he says. While an atom is an atom, there was no guarantee that recycling would produce a totally pure metal product, instead of one with irregularities or extra gunk that would mess up the final cathode design. Next, Redwood is working to scale up production and have its material tested by battery and EV makers.

What’s likely to be even trickier for Redwood is obtaining enough recycled atoms to reduce demands for mined ones. Few electric vehicles are old enough to be recycled—and those that are getting up there in years are lasting longer on the road than analysts expected. In the meantime, Redwood and other recycling startups are competing to secure a diverse array of battery sources, including from hybrid cars (a good source of nickel), power tools (which commonly use lithium manganese oxide batteries), and small devices like phones that, despite their tiny batteries, often contain a high ratio of cobalt. “We still feel very comfortable that, based on our feedstock, we’ll be able to source 30 percent recycled nickel and 30 percent recycled lithium,” Nelson says. Due to declining demand for cobalt in newer battery designs, he expects recycling to cover all of Redwood’s needs for the metal.

Still, the company will also need to source plenty of new material for its cathodes, just like battery makers everywhere. “I think it’s important to look at Redwood more as a materials company than as a recycler,” says Melin. He points out that the company currently sources about half of its material from scrap discarded by battery makers—which, while good to reuse locally, isn’t actually material that’s getting its second run in a battery cell. That’s likely to remain the case for some time, he says, as the flow of dying batteries remains a trickle relative to demand for new ones. In the meantime, he adds, the world will need many more mines.

October 13, 2022 By Editor

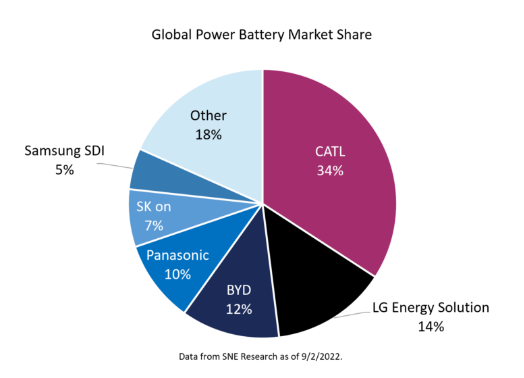

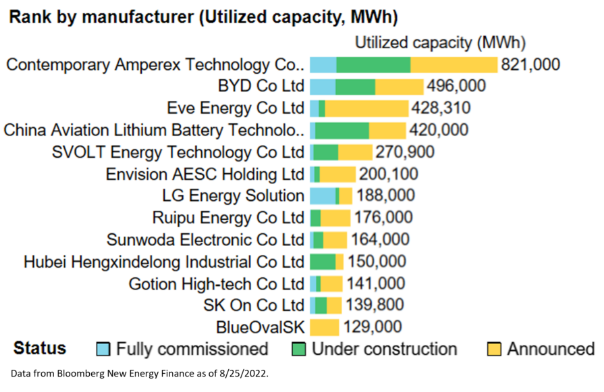

Contemporary Amperax Technology Co., Ltd (CATL) is the global leader in electric vehicle batteries and is the main supplier for companies such as Tesla, NIO, Ford, BMW, and more. CATL is also a Chinese company and trades on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, meaning that access to it is limited for most investors and requires access to China’s A shares market, which KraneShares provides through various ETFs.

CATL was founded by Yuqun Zeng, who grew up a poor farmer until high marks on his college entrance exams led him to ultimately graduate as one of the top engineers from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, a top school in China. Zeng became the second most wealthy individual in China, surpassing even Alibaba’s founder, Jack Ma, and built his company’s headquarters in the same rural area as his hometown.

The company started in 1999 as a spin-off from Amperex Technology Limited producing batteries for consumer electronics before EVs took off in 2011 in China. CATL was established in 2012 and has grown by leaps and bounds as EV battery demand took off in China, the world leader in EV production and sales, and then spread globally.

“China is now the world’s largest country for EV sales, with 3.3 million EVs sold in 2021, accounting for around 50% of global sales. CATL gradually established its position as a leading supplier and now holds nearly 50% of the market share in China,” wrote Derek Yan, CFA director of investments at KraneShares, in a recent paper.

CATL is currently predicting that its Q3 profit could triple as EV demand continues to grow at a healthy pace in China. According to the China Last Night blog, electric vehicle sales in China now make up 27.1% of all new car sales as of September, and production has increased 110% while sales have increased 93.9% year-over-year.

The company is expanding aggressively, building factories in North America and Europe that will allow it to increase its total annual capacity to 500GWh by 2025 and 800GWh by 2030. Its partnership with companies such as Tesla and Ford as a core battery supplier have the company positioned in a continued place of prominence as EVs continue to gain market share.

CATL has built its success on a foundation of innovation and efficiency: in 2021, its central factory in Ningde was awarded as a Global Lighthouse Factory by the World Economic Forum, which recognizes manufacturers for utilizing advanced technologies in their operations. Its factories blend artificial intelligence, advanced analytics, 5G, edge and cloud computing, and more to run efficiently, maximizing productivity while retaining safety and quality standards.

In a world that has been plagued by supply chain issues, CATL has been playing to its home team advantage: China currently holds over half of all battery-grade metal refining capacity globally across every major raw material used in battery production. This includes cobalt (73% of the world’s supply), nickel (68%), manganese (93%), and 100% of the graphite that lithium-ion batteries use.

CATL has taken that one step further, though, and is looking long-term.

“The firm also invests in mineral resources and battery recycling to hedge the rising cost of raw materials. CATL’s battery recycling unit, Pubang, can recycle 99.3% of Nickle, Cobalt, Manganese, and 90% of Lithium from used batteries,” wrote Yan. “When the battery market reaches a certain size, the industry could rely on recycling for most raw materials.”

CATL is a company firmly committed to innovation and remaining on the front-end of the technology curve, spending a healthy portion of its revenue on R&D. The research team at the company is comprised of more than 10,000 individuals, and CATL has logged 4,445 patents worldwide as of 2021.

“We believe more local Chinese companies like CATL will become leaders in the next phase of global growth. CATL and other companies listed on the Shanghai or Shenzhen Stock Exchanges are classified as China A-Shares, which are in the process of being fully included by MSCI in global indexes,” Yan explained, but most investors only have exposure to China through U.S. markets or Hong Kong.

“They are under-allocated to China A-shares, despite them accounting for half of the market cap of Chinese equities. Thus, China A-shares show a very low correlation to global equities,” Yan wrote.

KraneShares currently offers exposure to CATL through various ETFs with different investment strategies. The KraneShares Bosera MSCI China A Share ETF (KBA) invests in Chinese A-shares from the MSCI China A 50 Connect Index, an index of large cap companies across sectors in China, and CATL is the second largest holding at 7.02% weight. The KraneShares Electric Vehicles and Future Mobility ETF (NYSE: KARS) offers a good solution for investors looking to capture the potential growth of major EV producers globally and tracks the Bloomberg Electric Vehicles Index, and CATL is at top 10 holding at 3.43% weight. The KraneShares MSCI China Clean Technology Index ETF (KGRN) capitalizes on investing in clean technology in China’s growing economy — CATL is the top holding at 8.68% weight.

October 12, 2022 By Editor

Honda Motor and LG Energy Solution on Tuesday said a new multibillion-dollar plant to produce batteries for electric vehicles will be located in Ohio.

Construction of the new facility – located about 40 miles southwest of Columbus – is expected to begin in early 2023, followed by mass production of lithium-ion batteries by the end of 2025.

The battery plant is expected to cost $3.5 billion, with overall investment by the unnamed joint venture eventually reaching $4.4 billion, the companies said.

Honda and LGES announced plans for the joint venture and battery plant last year, but had not revealed a location. The facility is expected to employ about 2,200 people, the companies said.

In addition to the new battery plant, Honda on Tuesday said it plans to invest $700 million to retool several of its existing auto and powertrain plants for production of EVs. The Japanese automaker expects to begin production and sales of EVs in North America in 2026.

The announcements are part of several recent multibillion-dollar investments in U.S. production of EVs and batteries amid tightening emissions regulations and legislation to encourage domestic manufacturing.

Automakers are facing stricter sourcing guidelines that are part of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (formerly the North American Free Trade Agreement) and, more recently, the Inflation Reduction Act. Both policies increased requirements for domestically sourced vehicle parts and materials in order to avoid tariffs or qualify for financial incentives.

Honda has plans to phase out traditional internal combustion engines and exclusively offer battery-electric and fuel cell electric vehicles by 2040 in North America. It’s part of the company’s plans to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

LGES – a spinoff from LG Chem – has also announced joint ventures with General Motors, Hyundai Motor and Jeep maker Stellantis

October 11, 2022 By Editor

Carmaker Stellantis has signed a non-binding preliminary agreement with GME Resources to secure supplies of nickel and cobalt sulphate for electric vehicle (EV) batteries, the two companies said on Monday.

The deal marks a further move by the world’s fourth largest carmaker to lock down supplies of metals needed for batteries that power EV cars, ahead of an expected surge in global demand as a transition towards cleaner mobility gains traction.

Earlier this year the Franco-Italian group signed a lithium supply agreement with developer Vulcan Energy Resources and said it would invest 50 million euros ($48.6 million) to buy an 8% stake in it.

Stellantis and the GME mining company said in a statement on Monday that the memorandum “represents the first step toward a potential long-term partnership,”.

Financial details were not disclosed.

The supply will come from a nickel and cobalt advanced mining project in Western Australia called “NiWest”, which GME is currently developing, with a planned production of around 90,000 tonnes per year of battery-grade nickel and cobalt sulphate.

A feasibility study for NiWest is due to start this month, the companies said.

Stellantis Chief Purchasing and Supply Chain Officer Maxime Picat said that securing the raw material sources and battery supply would strengthen the group’s value chain for EV production and support its decarbonisation target.

Stellantis, the owner of brands including Jeep, Peugeot, Fiat, Citroen, Maserati and Opel, has pledged to make up 100% of its sales in Europe and 50% of its sales in the U.S. from battery electric vehicles by 2030.