London-based Pensana (LSE: PRE) is being backed by one of the United Kingdom’s largest asset managers and the Angolan sovereign wealth fund to build a rare earths refinery in England and a mine in the African country.

M&G Investment Management, which has £342 billion under management, and the roughly $3 billion Angolan fund (FSDEA) are investing a further $10 million to increase their respective stakes in Pensana to 13% and 23%, the company said in a news release on Friday.

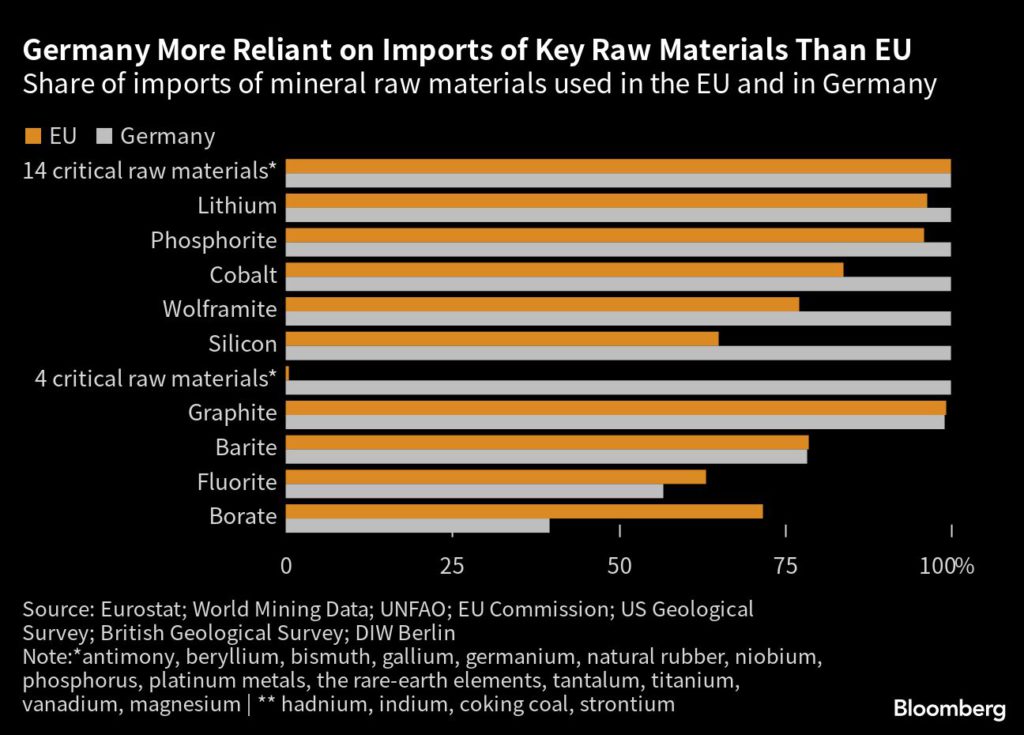

Pensana has started to build a $195 million plant at Saltend in the port of Hull in northeast England that would be fed with ore from a $305 million mine in the southwest African country more widely known for diamonds and oil than rare earths. The refinery would be one of only a handful of its kind outside China if it starts as planned in 2026.

“This additional investment reflects their confidence in our strategy and growth prospects, and we are grateful for their ongoing commitment,” Pensana chairman Paul Atherley said in the release. “The fact that M&G and FSDEA have also requested the right to participate in any future equity raises is a clear endorsement of our business.”

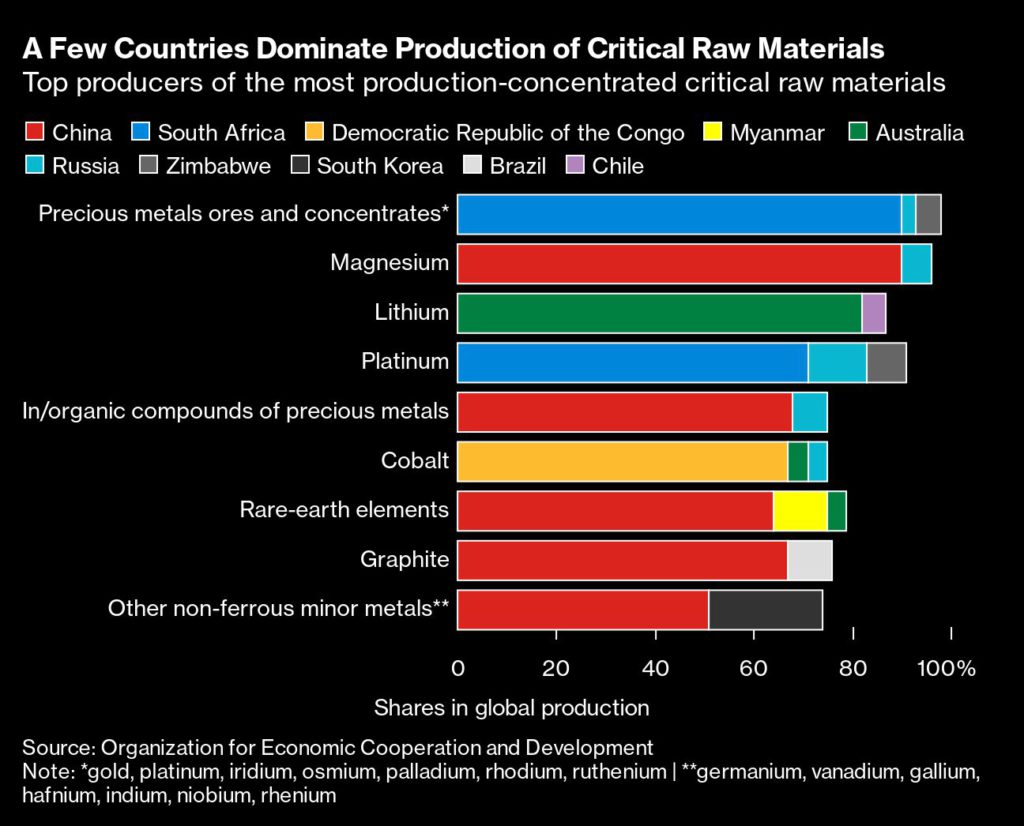

OPEC-member Angola is keen to diversify its oil-dominated economy while Pensana and M&G see opportunities in the surging market for metals in the green energy transition. Also, the UK is among Western countries investing billions to dislodge China from its domination of the critical minerals industry. Pensana has received funding from Britain’s £1 billion Automotive Transformation Fund.

The neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) Pensana would mine in Angola is used to make magnets in electric vehicle motors. The company has a partnership with automaker Polestar, which is controlled by Volvo, itself now part of Geely owned by Chinese billionaire Li Shufu.

The new investment, split equally between the two investors, follows a $4 million investment by M&G in December and £10 million a year earlier. The Angolan fund held 23% of Pensana in April 2021, but it wasn’t immediately clear how much it had invested or how its stake changed over the last two years to still show 23% now.

20-year mine

The project combining the open-pit mine and UK processing plant has a net present value of $2.2 billion at an 8% discount rate for an internal rate of return of 52%, according to a company report in October.

The life of mine is estimated at about 20 years, producing 1.5-million tonnes of ore annually and 40,000 tonnes of mixed rare earth sulphides (MRES) a year for the Saltend refinery. Its output is forecast at 12,500 tonnes a year of total rare earth oxides (TREO) including 5,000 tonnes of NdPr.

Angola, the fourth-largest diamond producer by value, would host the proposed mine at Longonjo, some 275 km inland from the port of Benguela. The site is 5 km from a main road and the historic Benguela railway running from the Atlantic to Zambia that China refurbished for billions of dollars in oil-backed loans about six years ago.

Operating costs at Longonjo would be $127 million a year or $3,943 per tonne of MRES. Saltend would cost $59 million a year or $6.40 per kg of TREO and $17 per kg of NdPr to run.

The 31-sqkm proposed mine site has proven and probable reserves of 30.1 million tonnes grading 0.6% NdPr, 2.6% TREO for 166,000 tonnes contained NdPr and 747,000 tonnes contained TREO, according to a Sept. 2022 estimate done according to the Australian mining code.

A hydro-electric power line and the provincial capital of Huambo, once a staging ground for rebels in the country’s decades-long civil war that ended in 2002, lie 50 km to the east.

Shares in Pensana gained a third of their value on Friday to close at 32.9 pence, within a 52-week price range of 21.8 pence to 86.9 pence, valuing the company at £62.8 million.