Amid a surge in demand for rechargeable batteries, companies are scrambling for supplies of lithium

SQM, Chile’s biggest lithium producer, is the kind of company you might find in an industrial-espionage thriller. Its headquarters in the military district of Santiago bears no name. The man who for years ran the business, Julio Ponce, is the former son-in-law of the late dictator, Augusto Pinochet.

He quit as chairman in 2015, during an investigation into SQM for alleged tax evasion. (The company is co-operating with the inquiry.) Last month it emerged that CITIC, a Chinese state-controlled firm, may bid for part of Mr Ponce’s controlling stake in SQM, as part of China’s bid to secure supplies of a vital raw material.

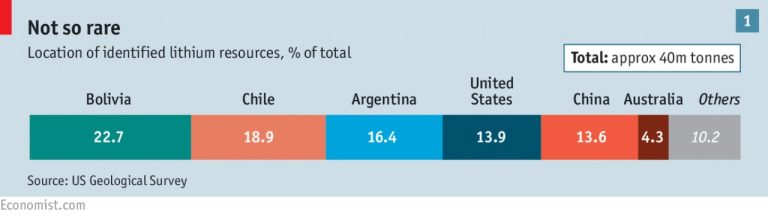

The focus of CITIC’s interest appears to lie on a lunar-like landscape of encrusted salt in Chile’s Atacama desert. It is a brine deposit washed off the Andes millions of years ago, containing about a fifth of the world’s known lithium resources. (Even more are in adjacent Bolivia but they are mostly untapped; see chart 1.) Just weeks before, CITIC had bought a stake in a Hong Kong electric-vehicle maker that uses lithium-ion batteries, indicating its growing interest in clean-energy technologies.

At SQM’s facilities the brine is pumped from an underground reservoir into hundreds of ponds. As it evaporates it turns into shades of blue and green, making the plant resemble a giant artist’s palette. It produces mostly potassium compounds but also a viscous liquid, lithium chloride. This is taken by tanker to a plant near the coast where it is turned into finely powdered lithium carbonate and hydroxide, which are then shipped around the world.

It is not a big business: lithium accounts for only about 5% of the materials in some car batteries, and for less than 10% of their cost. Worldwide sales of lithium salts are only about $1 billion a year. But the element is a vital component of batteries that power everything from ca

rs to smartphones, laptops and power tools. With demand for such high-density energy storage set to surge as vehicles become greener and electricity becomes cleaner, Goldman Sachs, an investment bank, calls lithium “the new gasoline”.

SQM is part of a global scramble to secure supplies of lithium by the world’s largest battery producers, and by end-users such as carmakers. That

has made it the world’s hottest commodity. The price of 99%-pure lithium carbonate imported to China more than doubled in the two months to the end of December, to $13,000 a tonne (see chart 2).

The spike mostly reflected concerns about the future liquidity of China’s spot market. China gets much lithium from spodumene rock in Australia, an alternative to South American brine. Albermarle, an American miner, and Tianqi, its Chinese joint-venture partner, plan to use spodumene from a big Australian mine to process more battery-grade lithium carbonate and hydroxide. That will mean less ore available on the spot market in China.

The industry is fairly concentrated, which adds to the worry. Last year Albermarle, the world’s biggest lithium producer, bought Rockwood, owner of Chile’s second-biggest lithium deposit. It and three other companies—SQM, FMC of America and Tianqi—account for most of the world supply of lithium salts, according to Citigroup, a bank. What is more, a big lithium-brine project in Argentina, run by a joint venture of Orocobre, an Australian miner, and Toyota, Japan’s largest carmaker, is behind schedule. Though the Earth contains plenty of lithium, extracting it can be costly and time-consuming, so higher prices may not automatically stimulate a surge in supply.

Demand is also on the up. At the moment, the main lithium-ion battery-makers are Samsung and LG of South Korea, Panasonic and Sony of Japan, and ATL of Hong Kong. But China also has many battery-makers. Adam Collins of Liberum, another investment bank, talks of an “inflection-point” in Chinese demand for lithium salts. Its government is stepping up the promotion of lithium-ion batteries and electric vehicles, with the biggest emphasis on buses. Sales of “new energy” vehicles in China almost tripled in the first ten months of 2015 compared with the same period in 2014, to 171,000 (though they remain less than 1% of total vehicle sales).

Tesla Motors, an American maker of electric cars founded by Elon Musk, a tech tycoon, is also on the prowl. It is preparing this year to start production at its “Gigafactory” in Nevada, which it hopes will supply lithium-ion batteries for 500,000 cars a year within five years. J.B. Straubel, Tesla’s chief technical officer, says the firm wants to secure supplies of many battery materials, not just lithium. “There’s so much hype in the lithium market right now…people look at it as this magical element,” he says. Nonetheless, in August Bacanora, a Canadian firm, said it had signed a conditional agreement to supply Tesla with lithium hydroxide from a mine that it plans to develop in northern Mexico. Bacanora’s shares jumped on the news—though analysts noted that shipping fine white powder across the United States border would need careful handling.

Bigger carmakers also have a growing appetite for lithium. In a recent shift, Toyota has begun offering lithium-ion batteries instead of heavier nickel-metal hydride ones in its Prius hybrid. Mr Collins notes that tougher emissions standards in Europe and America are likely to boost carmakers’ need for lithium.

Another big source of demand may be for electricity storage. The holy grail of renewable electricity is batteries cheap and capacious enough to overcome the intermittency of solar and wind power—for example, to store enough power from solar panels to keep the lights on all night. Tesla says that next month it will start installing “Powerwall” battery packs in American and Australian homes to store solar energy, at a cost of $3,000. Enel, an Italian utility, is launching similar storage products this year in South Africa, where homes and businesses suffer frequent black-outs.

Power utilities will increasingly use giant battery packs, charging them at times of low demand and tapping them to provide short bursts of electricity at peak times, an alternative to building a fossil-fuel plant that will sit idle the rest of the time. AES Energy Storage, a big provider of energy storage, won a contract in 2014 to provide a “peaker plant” in Southern California that will provide up to 100 megawatts (MW) of power into the grid at moments of maximum demand. In December, the firm agreed to buy, over several years, enough lithium-ion batteries from LG to provide ten times this level of peak power—that is, 1 gigawatt, or more than the output of an entire, typical-size coal-fired power station. “We’re hybridising the power grid,” says John Zahurancik, its boss.

Lithium-ion technology nonetheless attracts legions of sceptics—and not just petrolheads. In a paper published last month, researchers linked to the federally-funded Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago wrote that large-scale batteries need to offer hundreds of miles of driving range, be rechargeable in minutes instead of hours, and provide power at costs comparable with natural gas. These demands are “beyond the reach” of lithium-ion technology, they argued. Tesla’s Mr Straubel, however, foresees at least another doubling in the performance of lithium-ion batteries, and thinks lithium will continue to shape the battery of the future.

The juice still to be squeezed from lithium-ion batteries can be seen at the Angamos power plant on Chile’s northern coastline. It uses 1m lime-green battery cells in ten shipping containers to regulate the electricity grid across the Atacama region at times of peak demand, including at SQM’s lithium-mining operations hundreds of miles away across the desert. For the lithium the power plant uses, it is a homecoming. Extracted at SQM, it was sent to China to be turned into cells, put into battery packs in America, and shipped back to Chile by AES Energy Storage. That is a long journey for a tiny element of a little battery cell—but one that may embody the future of the world’s energy supplies.