Confronting the threats posed by climate change will require transitioning to renewable energy. Thankfully, access to decentralized power systems — including a projected 72 million solar-powered homes — will expand access to electricity more cheaply and more sustainably than past estimates, industry analysts say.

It’s been over a century since the first electric grids went online and utility companies still can’t get power to about 14 percent of the world’s population. But a new report by analysts working for Bloomberg New Energy Finance argues that decentralized systems, including those powered by renewables, could and should close the gap in an environmentally sustainable way. In fact, they estimate that the total industry investment required to achieve this is approximately $372 billion dollars less than recent assessments by the the International Energy Agency.

The BNEF group’s head researcher, Itamar Orlandi, writes that the IEA “appears to assume costs well above those we already see in the market.”

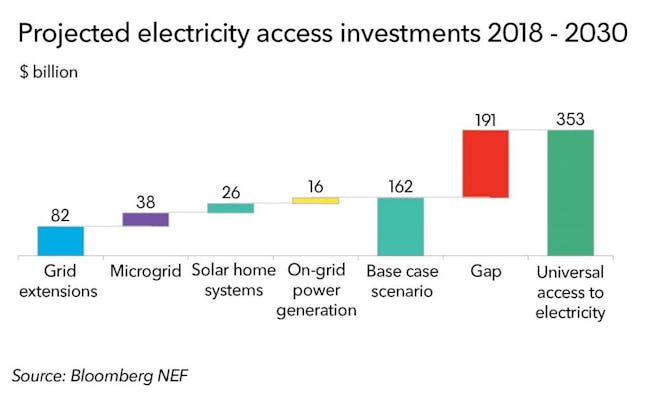

About $162 billion is currently likely to be spent on expanding energy access, according to Orlandi, with about $191 million needed to close the gap to universal access.

The Benefits of Decentralized Energy Systems

In significant ways this is the kind of report that’s mainly meant for government policy makers and decision makers at major investment institutions. But the report’s emphasis on decentralized energy grids aligns with the United Nations’ High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development — which is finishing its annual meeting sometime later this week.

The director of the UN’s Industrial Development Organization, Li Yong, set the tone with a statement late last month reiterating a similar agenda on the path toward 2030.

Specifically, Yong called on nations to “move towards decentralized energy systems which entail decentralized energy generation and storage, as well as community involvement.” To get us there, he pushed for “funding options to enable investment for low-carbon infrastructure and the deployment of leap-frogging technologies.” Lastly, he reemphasized the UN’s commitment to a “leave no one behind” energy policy for 2030.

Here’s how Orlandi and his fellow analysts foresee this shaking out: Energy companies, they say, will focus their efforts on the last handful of places where traditional, old-school grid extensions remain economically viable until sometime around the mid-2020s. It now costs somewhere between $266 and $2100 to connect a single household to the pre-existing energy grid, they estimate, but that cost doesn’t pay itself back quickly enough in communities with modest power demands. Roughly, 892 million people currently live on less than $5.50 per day with very modest electrical power demands.

What that means is that certain renewable energy options whose price-per-kilowatt-hour would not really be competitive in certain affluent, energy intensive areas (i.e. certain home solar systems or community level microgrids) can and do suddenly become more cost effective option elsewhere. After that, the report anticipates that a confluence of emerging trends will make the renewable transition even more likely in the years to come: ongoing improvements in energy-efficient appliances, cheaper component parts, more established renewable energy supply chains, and new economies of scale in the home solar market.

“Of the 238 million new households to get electricity between now and 2030,” Orlandi writes, “72 million will use solar home systems and 34 million will benefit from microgrids.”

These are very pleasant prognostications. Hopefully they come true.